As the Light Changes: Embracing the Ephemeral in Psychosocial Oncology and Acute Palliative Care

Marcia Brennan

https://doi.org/10.52713/RDKI5912

Abstract

Drawing on her clinical experiences as a literary artist at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Marcia Brennan examines the various ways in which aesthetics can serve as a form of care for people facing the end of life. The literary artworks produced in acute palliative care often appear as meditations on multiplicity, particularly as people reflect on key transitional moments of life, such as birth, marriage, and death. Ultimately, the artworks provide insight into how to hold multiple perspectives simultaneously as the world appears in a new light. This essay includes several original literary artworks and accompanying questions for teaching and discussion.

Introduction: As the Light Changes

One day I met an older woman who was facing the very end of her life. As we visited together, I asked her about the imagery that was meaningful to her. She shared a very moving description of Houston, her beloved adopted city of many decades. As the woman spoke, I wrote her words down verbatim, and then I read them back to her. When she heard her story read aloud, the woman was extremely moved, and she gave me permission to share her narrative:

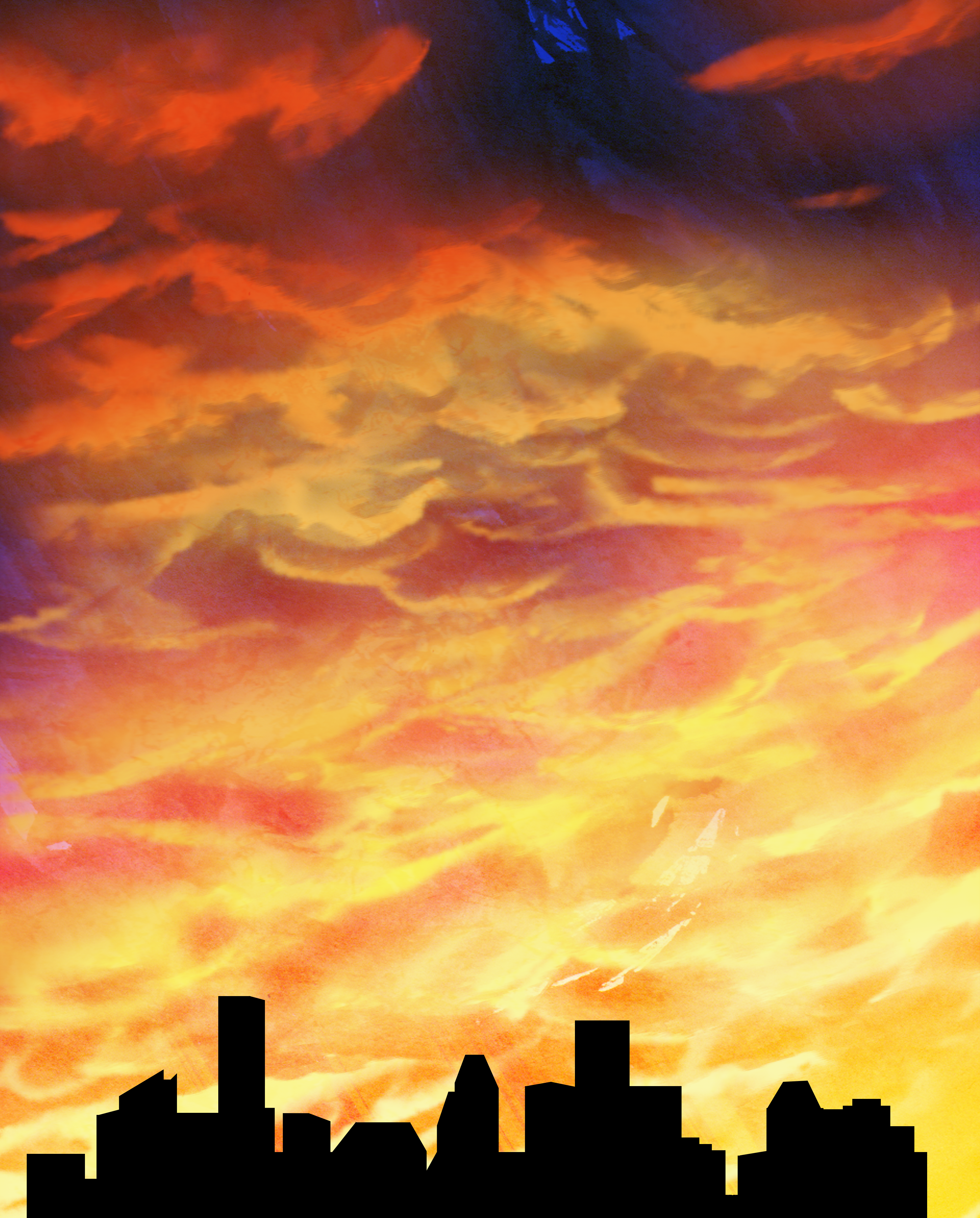

Houston, as the Light Changes

One thing that stands out to me is the Houston skyline.

It’s the view when I’m driving in.

I’ve seen the skyline where it looks like there is a huge pall over it,

And sometimes it looks like a huge clearing.

That is my special image of coming into Houston.

It’s an extraordinary city.

It’s the symmetry—or the serendipity.

I couldn’t even say which.

It’s the extraordinary coming together of things that change.

There is no other place in the world where people are like Houstonians.

There’s just a coming together of everything.

It’s like the skyline.

Each of those buildings is so different, and so unique,

Especially, as the light changes,

And reflects off the glass.

It’s ephemeral—like a sunset,

And I collect images of sunsets.

I’ve been to so many places all over the world,

And there is something so special—

And so different—

About Houston.

You can really see it

As the light changes.

In the woman’s narrative, the city of Houston appears like a mosaic of shifting lights and transitory presences. On both the existential and the metaphorical levels, these themes are reflected in the ever-changing skyline. In this tale of proximity and convergence, the city appears to be at once iconic and abstract. That is, subjects appear to be coming into form and going out of form, all within the framework of a single image. By incorporating these seemingly oppositional states of being into a unified framework, the story provides a vivid means to envision the ephemeral.

Such themes arise not only when individuals describe images of shifting landscapes such as sunsets, but when they reflect on key transitional moments of life such as birth, marriage, and death. In this essay, I examine the unique ways in which these themes become expressed in the poetic narratives that people tell when facing life at the end of life.

The Artistic Practice: Literary Aesthetics and Psychosocial Oncology

By training, I am a modernist art historian. In my day job, I am a Professor of the Humanities at Rice University, where my teaching and research engage the fields of Modern and Contemporary Art History, Religious Studies, and the Medical Humanities. Since early 2009, I have also served as a literary Artist In Residence in the Department of Palliative, Rehabilitation, and Integrative Medicine at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Since early 2021, I have expanded this practice to work remotely with general oncology patients at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. In both contexts, my clinical work is sponsored by COLLAGE: Art for Cancer, a nonprofit organization conceived and founded by Dr. Jennifer Wheler.[1] COLLAGE provides innovative arts programming for people living with cancer. Through my friendship with Dr. Wheler, I became inspired to serve as a literary artist. Over the years, it has been my privilege to work with thousands of people, and to be present during hundreds of passings.

Early on, I developed a set of questions that are well-suited to this work. While the answers that people provide are always unique, the questions themselves remain constant. If the person in the bed is alert and oriented, I will typically say to them: “If I were to ask you if there is an image in your mind of something that holds special meaning and value for you—and, it can be anything in the whole world, as long as it is something close to your heart—what would that be?” I may also ask the person what they love to do. If the patient is not capable of such interactions, I will turn to those around them and invite them to tell me something wonderful—absolutely wonderful—about the person. As people speak, I write down their words verbatim. Through the course of the visit, I arrange the words into successive lines that resemble non-rhyming poetry. I then read the narrative aloud, while making any changes or corrections that individuals indicate. I have found that poetry is particularly well-suited to this work. Just as the vertical format of a poem is intrinsically monumental, poetry can emulate human presence in a way that prose simply cannot. When I work bedside at the hospital, I inscribe the poem in a handmade paper journal, which the person is able to keep as a gift for themselves and their family. When I work remotely, I subsequently email the person their story.

Occasionally I receive referrals from hospital colleagues requesting that I visit with a particular patient or caregiver. Sometimes members of the clinical team will also inform people about the Literary Arts Program, and they will express an interest in this service. Beyond these referrals, the visits typically unfold with the patients and caregivers who happen to be on the hospital unit on any given day. Priority is given to those who are in the most acute states of suffering. If a person is actively dying, I make it a point to offer my services as a gift for the family. During one shift, I can see up to four patients. The visits can last anywhere from ten minutes to three hours; it is truly impossible to know beforehand how long any given visit will take. All of the work is completed in a single sitting, and I only interact with patients and caregivers once. Beyond this, there is no predetermined protocol for this work. Patients and caregivers have no advance preparation for the visits. I have found this open-ended approach to be highly effective. This is not a structured interview process, but a creative interaction in which people can freely choose to participate. The conversations flow naturally and gracefully. At the end of the visit, it is crucial that people are able to recognize the authentic character of their own voice when they hear their beautiful words spoken aloud.

Technically, this work is positioned at the intersection of literary aesthetics and psychosocial oncology.[2] Put another way, as an artist, I work in the media of language and human consciousness. Within these challenging clinical settings, I have found that it is necessary to acknowledge what is there, and then, to hold space for other visions and possibilities to emerge. Thus, patients and caregivers provide the content of the stories, while I provide the practical means for the artworks’ realization. As this suggests, this is not art therapy. Rather, it is a creative intervention in applied literary aesthetics within the clinical domain. Just as there is no predetermined protocol, there is no set of assessment metrics associated with this work. Instead, these are open-ended encounters that engage the instrumentalized use of art for expression and transformation.

While doing this work, I have repeatedly seen the ways in which the narratives provide a meaningful, humanistic dimension that enriches the perspectives, not only of patients and caregivers, but of healthcare providers, students, and anyone else who hears them. (At the end of this essay, I offer a related pedagogical exercise, with accompanying discussion questions.) On so many occasions I have seen how discussing the stories offers a valuable means for individuals to reflect on their own challenging experiences, and on the moving encounters that they have had with people facing the end of life. I have also seen how people are often moved to tears when they hear the beauty and power of the artworks. Sometimes I am moved to tears, as well—and you may be, too, as you read the stories.

The Eyes of a Child: Shifting Visions of Multiplicity and Transition

One afternoon, my final visit of the day was with a lively woman who told me how she loved to watch her grandchild pray:

The Eyes of a Child

My image is of a child praying.

I think that is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

To me, there’s more grace in that

Than in anything else I’ve ever seen.

The face of a child changes

When they are praying honestly.

They don’t know that faith can be misused.

They believe that, if you talk to God,

He’ll answer you.

It’s so short lived,

And it’s a true miracle,

When you see it.

I’ve always seen the world this way.

It’s a choice,

To see the world

Through the eyes of a child.

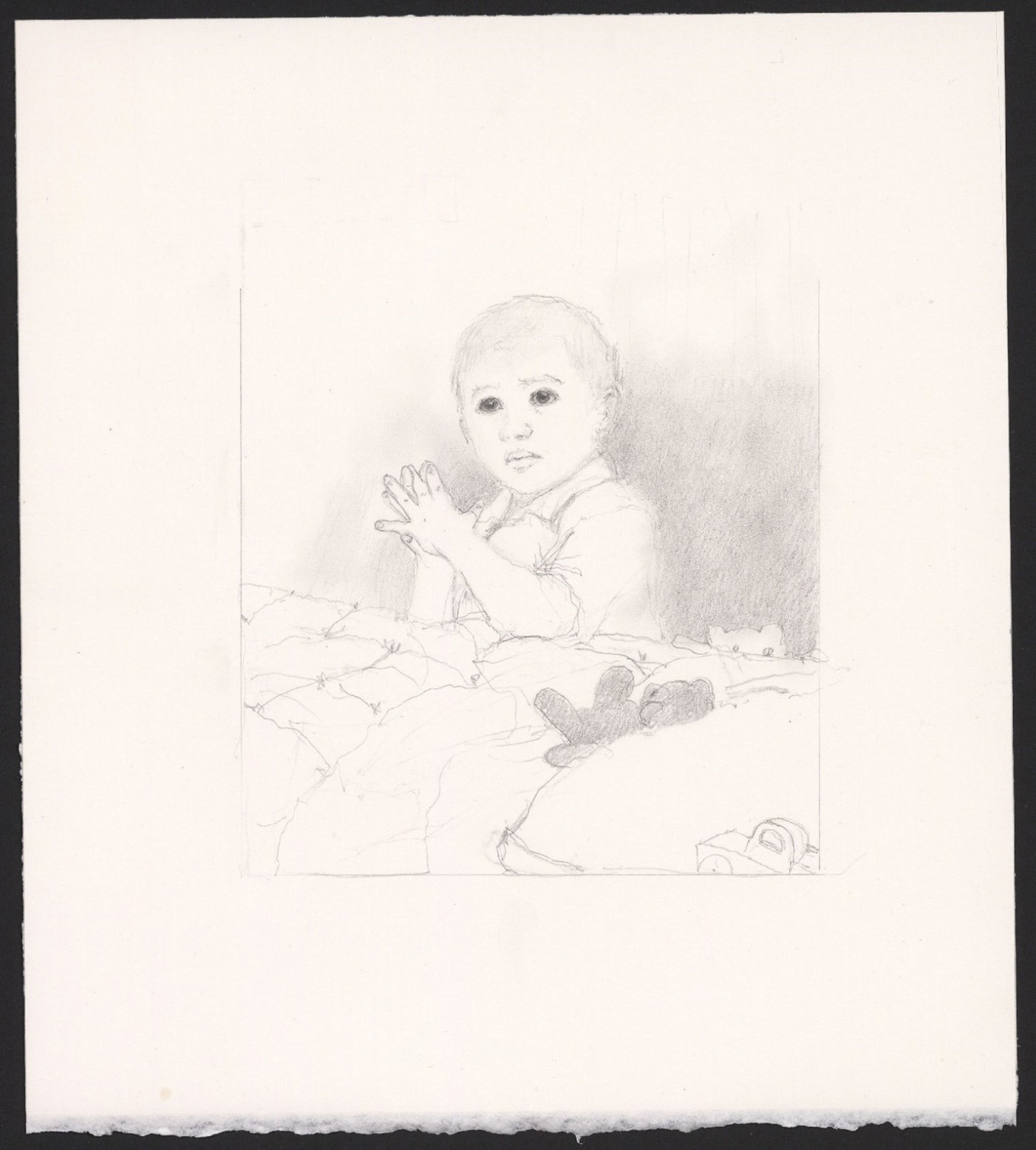

After this visit, I commissioned an illustration of this story from the West Coast visual artist Lynn Smallwood. In this tender pencil drawing, a small boy kneels at his bedside, saying his evening prayers amidst his scattered toys. The child’s hands are firmly clasped together, and his expression is decidedly intent, even as his eyes are filled with trusting innocence. Taken together, these visual and poetic artworks raise a fascinating paradox: they show us that the youngest part of ourselves is also the oldest part of ourselves. That is, the very oldest part of a person dates to their earliest moments of life. This insight offers a novel perspective on mortality and transience, and on how innocence and wisdom can appear, not as opposites, but as coextensive presences.

My Grandbaby: Multigenerational Bonds

Extending the theme of shifting and continuous presences, one day I met a lovely, middle-aged woman and her sister—not in the patient’s room, but first in the elevator going up to the 12th floor. Unlike most acute intensive palliative care patients, this woman was still ambulatory, although she was gravely ill. She suffered from a severe bowel obstruction, and only a few days before, she had actually been nonresponsive. Yet that afternoon, she was in her wheelchair returning from a visit to the butterfly garden. The woman was fully oriented as she spoke eagerly about her expected grandchild:

My image is of my grandbaby.

She’s not been born yet,

But, she’s coming—probably in early fall.

This is my daughter’s baby,

And it’s going to be a girl.

This is special because of the time,

With me going through all this.

The baby is a little girl,

And this makes me excited.

Hopefully, I’ll be there to see it.

I want this baby to know that she is very loved.

And, that she makes me feel loved.

When the woman and her sister heard this reciprocal story of loving and being loved, they were both moved to tears. Once again, the narrative threads through multiple domains of being, uniting individuals who are present yet preparing to leave with those who are not yet here but preparing to arrive. The woman’s story of her unborn granddaughter thus represents a powerful meditation on continuity and transience, and on the ways in which love can be present both within and beyond the finite parameters of a human lifetime.

Family Details of Intergenerational Continuities

Related themes can arise when people who are facing advanced illness and the end of life contemplate their relationships with relatives who have passed on, yet with whom they continue to feel close bonds. Sometimes these connections not only unfold on the emotional level but are also recognized in the physical body. One woman described this phenomenon through what she lovingly referred to as

Family Details

I remember my father’s hands,

And his hugs.

I see my dad in my own hands.

Even though he’s gone now,

When I look at my own hands,

I know that he’s still here.

With age, I crave that closeness.

The woman’s story is at once strikingly corporeal and notably subtle, as she describes sensing her father’s presence, and feeling very close to him, each time she looked at and worked with her own hands.

Another man told a tender story about his relationship with his deceased grandfather. Since early childhood, this middle-aged man had loved cars. He didn’t just like cars. He loved cars. He loved to drive them, to race them, and to work on them—and it was the latter interest that he shared with his beloved grandfather. As the man told me:

We Share the Same Face

Have you ever heard the phrase, “Skip a generation”?

My dad’s father was a diesel mechanic.

Being around him, tinkering in the garage,

Led me to think that that was neat.

My oldest memory of this goes back many decades.

My grandfather was from Italy.

I felt like, when I was with him,

I was learning something useful:

Working with my hands.

This allowed us to bond.

I think my grandparents are around me.

I look like my grandfather.

We share a natural bond.

We share the same face.

Such stories shed important light on cherished conceptions of intergenerational continuities. Recognizing the presence of a person who is no longer here within the living forms of one’s own hands or face evokes a sense of composite presence. This quality becomes especially intense when the stories are infused with an enduring sense of love. Such imagery also expresses a powerful conjunction of the singularity and the multiplicity of life, and of lives—and of how our unique existences are embedded within continuous patterns of creation.

Even More: An End-of-Life Wedding Story

One day I met an older couple who had been married earlier that morning. By the time I entered the room late that afternoon, the man was actively dying. His breathing had changed, and the characteristic rattling sound was audible in his throat.

Although he was extremely weak, earlier that day the man and the woman had been married in a religious ceremony. When I first walked into the room, I noticed a bouquet of white roses with lush green leaves sitting in a small square vase on the bedside tray table. I soon learned that, while the man and the woman had been legally married for many decades, they had never been married in the Catholic Church. Even as the woman and I watched her husband pass away, she told me a very moving story about how, earlier that day, the family’s life had expanded

Even More

My husband is the one who wanted to get married

Because he didn’t know if he would make it.

We wanted to get married in the church.

Today, everything was beautiful

Because the whole family was here, together.

It feels different, now that we are married.

We can receive the sacraments.

It’s the tradition we have, as Catholics.

A year ago we lost our son, in this hospital.

That made the marriage even more special.

We already knew that we cannot be wasting time.

So, we wanted to get married,

Even more.

As we chatted, the woman told me that, throughout the wedding ceremony, she felt her family’s presence, including the children and the grandchildren who were there, and the son who had passed away, and thus, who was no longer there. While clothed in extremely straightforward language, this end-of-life wedding story unites seemingly oppositional states of being, including loss and joining, separation and connection, grief and joy. The story poignantly evokes the ways in which unions can be created during periods of pronounced dissolution. Or, to phrase these complex themes within the simplicity of the woman’s language, for this family, what was more was even more.

You Know What Family Is: Mystical Visions and Predeath Visitations

As the stories exemplify, the narratives that emerge in Acute Intensive Palliative Care can reference people who are living here now, those who have yet to be born, those who are preparing to leave, and those who are no longer here and who have already passed on. These complex themes arose the day that I visited with a burly older man who was mourning the loss of his strength and mobility. As he lay in his bed, this man was looking both forward and backward at once. As we visited, the man described different members of the various generations of his extended Italian American family. While he spoke lovingly about his devoted wife, children, and grandchildren—that is, the people who are in his life now—he also vividly described images of the relatives who had passed on. The man then told a very tender story of the pre-death visitations he was having with his deceased mother.

Before sharing this story, I’ll note that such narratives can be particularly sensitive in a healthcare environment. While mystical experiences represent familiar topics in end-of-life care, they also remain the subject of much debate. Within the scholarly literature, and within my own personal experiences, I have seen how these narratives are sometimes celebrated as meaningful and valuable, and how they are sometimes dismissed as false or hallucinatory. Indeed, when people express their subtle spiritual experiences, the encounters can risk being devalued or written off as delusional, even as they may hold great meaning for the people involved. Ultimately, I would suggest that when we encounter such situations, the question we should be asking is not whether the story is true, but rather what meaning the story holds for the person telling it. In all cases, my advice is to listen respectfully and to consider the significance and value that the narratives can hold for the people involved.[3]

On that particular day, the man was moved to tears as he described his pre-death visions. Paradoxically, the man’s imagery was both shifting and continuous, ordinary and visionary. While the narrative is subtle and mystical, it is also extremely solid and grounded. That is, the man’s language is simple, clear, sincere, and direct, and his imagery is concrete and familiar. As the man told me:

You Know What Family Is

Being Italian, you know what family is—

The Sunday dinners.

We bless every meal.

For our family business, we had a bakery.

Now, when I wake up, I see my mom and dad,

And my brother who has passed.

I see my mom the most.

She looks like a little old Italian woman with a bandanna on her head,

Getting ready to make the bread.

When we first started the bakery,

We did it in the bottom of my mother’s house.

She kneaded the dough.

It would be like 5 a.m. and my mom was like,

“Let’s go. It’s time to make the bread.”

I see my mom a lot now,

And I call to her a lot.

She’s a good woman.

I want to tell my family:

Family is sacred,

Because of all of you.

Once again, this is a story of continuity and transition. Despite the controversial status of such narratives in end-of-life care, such stories can be extremely powerful not only for the people telling them, but for all of us. Again and again, the stories express the insight that, when facing death, we can see life. We can stay present, as the light changes.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude goes to Woods Nash for kindly inviting me to participate in Healing Arts Houston: Innovations in Arts and Health. The collaborative work discussed in this paper engages a research university (Rice University), two academic medical centers (MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania), and a nonprofit organization (COLLAGE: Art for Cancer). Such work vividly illustrates the value of such institutional collaborations, particularly when engaging vulnerable clinical populations.

It is an extraordinary privilege to work with distinguished medical teams. I would like to thank Dr. Eduardo Bruera, the F.T. McGraw Chair in the Treatment of Cancer and Chair of the Department of Palliative, Rehabilitation, and Integrative Medicine at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. My special thanks also go to Dr. Ahsan Azhar, Assistant Professor and Medical Director of the Acute Palliative and Supportive Care Unit of the Department of Palliative, Rehabilitation, and Integrative Medicine at MD Anderson. At the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, I would like to thank my colleagues Karen Anderson, David Cribb, Michael Guzzardi, Krissy Hill, Eletta Kershaw, Joanne Klein, Dr. Hayley Knollman, and Jaclyn Rieco. Above all, I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Jennifer Wheler and to the people who have so generously shared their stories. They have my deepest thanks.

Note Regarding Issues of Confidentiality

The images appearing in this chapter contain no recognizable likenesses that bear any resemblance to individuals with whom I have worked. In compliance with the federal standards of the United States Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), particular details relating to specific individuals have been altered or generalized so as to omit any identifiable data. These precautions are consistent with HIPAA compliance while preserving issues of confidentiality, particularly as specified under “The Privacy Rule,” The Belmont Report, and the Department of Health and Human Services Office for Human Research Protections, including The Common Rule and subparts B, C, and D of the Health and Human Service specifications as outlined in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) at 45 CFR 164 and 165, which specifies the “safe harbor” method of de-identification. By adopting this approach, the stories are presented in such a way as to make the subjects visible and to acknowledge the legal and ethical frameworks that make such representations possible at all. Thus, while the descriptions of encounters with patients and caregivers accurately reflect the nature of our interactions, and while the italicized texts are transcriptions of people’s statements, these elements are generically worded, thus rendering the subjects anonymous.

This work has been favorably reviewed by two independent Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at Rice University and at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Discussions Questions for Teaching

The end of life can represent an extremely challenging subject. As you begin your class, ask the students to take out a blank piece of paper and reflect on and complete the following sentence: “When I think about the end of life, the words that come to mind are…”

Explain that you are going to read aloud some literary artworks that were produced in a clinical setting, and that the stories contain the actual words of people facing the end of life. Read the narratives aloud and ask the students to note their reflections and feelings.

After reading several of the artworks aloud, tell the class, “Now that you have heard the stories, I want everyone to take a moment to reflect on and complete the following sentence: ‘When I think about the end of life, the words that now come to mind are…’”

Go around the room and invite everyone to compare their later reflections with their initial responses. Ask the students to consider how their perspectives may have shifted during this single class session. Ask them what they have learned from the stories, and from one another.

Additional Resources

Brennan, Marcia. 2017. Life at the end of life: Finding words beyond words. Bristol, UK: Intellect.

—. The Heart of the Hereafter: Love Stories from the End of Life. Winchester, UK: Axis Mundi, 2014.

—. Life at the End of Life: Finding Words Beyond Words. Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2017.

Charon, Rita. 2006. Narrative medicine: Honoring the stories of illness. New York: Oxford University Press.

Charon, Rita, et al. 2016. The principles and practice of narrative medicine. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gawande, Atul. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. New York: Picador, 2017.

Holden, Janice Miner, Bruce Greyson, and Debbie James. 2009. The handbook of near-death experiences: Thirty years of investigation. Santa Barbara: Praeger Publishers.

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. New York: National Academies Press, 2014. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17226/18748

Kaasa, Stein et al. “Integration of Oncology and Palliative Care: A Lancet Oncology Commission.” Lancet Oncology 19 (November 1, 2018): e588-e653. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7

Kellehear, Allan. The Inner Life of the Dying Person. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Kellehear, Allan. 2017. Unusual perceptions at the end of life: Limitations to the diagnosis of hallucinations in palliative medicine. BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care 7: 238-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001083

—. 2020. Visitors at the end of life: Finding meaning and purpose in near-death phenomena. New York: Columbia University Press.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Integration of the Humanities and Arts with Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in Higher Education: Branches of the Same Tree. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17226/24988

Saunders, Cicely, Mary Baines, and Robert Dunlop. Living With Dying: A Guide to Palliative Care. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- See information on the nonprofit COLLAGE: Art for Cancer ↵

- The work that I undertake as a literary artist is distinct from the approach pursued within Narrative Medicine programs. Regarding the ways in which this work differs from Rita Charon’s practice of narrative medicine, see my book Life at the End of Life: Finding Words Beyond Words (Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2017), 16-17. See also Rita Charon, Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), and Rita Charon et al., The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). ↵

- Regarding the phenomenon of individuals seeing visions of deceased relatives, friends, and other figures as they approach the end of life, see Janice Miner Holden, Bruce Greyson, and Debbie James, eds., The Handbook of Near-Death Experiences: Thirty Years of Investigation (Santa Barbara: Praeger Publishers, 2009), 231-32. For a literature review and a rigorous critique of the term “hallucination” as a diagnostic category associated with deathbed visions and near-death experiences, see Allan Kellehear, “Unusual Perceptions at the End of Life: Limitations to the diagnosis of hallucinations in palliative medicine,” BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 7 (2017), 238-46. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001083 As Kellehear observes, describing these subjects as hallucinations promotes a stigmatizing approach that is often associated with psychopathology. Regarding these sensitive subjects, see Allan Kellehear, Visitors at the End of Life: Finding Meaning and Purpose in Near-Death Phenomena (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020). ↵