Art Museum-Based Experiences to Build Skills for Clinical Communication and Medical Professionalism

Caroline Goeser; Anson Koshy; and Evan Leslie

https://doi.org/10.52713/ZBCN6445

Abstract

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) and the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics at the McGovern Medical School, UTHealth have collaborated in offering an elective Art of Observation course since the early 1990s. The three-session course, offered in both fall and spring semesters, is designed for first- and second-year medical and dental students, and each two-hour session takes place in the museum’s galleries. After the hiatus necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic, the course planning team capitalized on the immersive architecture and art installations in the new Nancy and Rich Kinder Building at MFAH to create opportunities for newly conceived, multisensory learning sessions. To heighten this multisensory experience, the team reached out to colleagues at the Moores School of Music in the College of the Arts at the University of Houston to add learning experiences with music, which many consider the most immersive of art forms. With these ingredients, staff from all three Houston institutions codesigned multisensory learning modules in direct response to learning goals that would fill gaps in the standard curriculum for medical and dental students in their first and second years. In this chapter, the collaborative team shares its experiences co-designing and implementing this Art of Observation course in the fall semester, 2021 and spring semester, 2022. The team also reflects on their new approaches to pedagogy, the research and evaluation collected from the students, and the pedagogical and logistical challenges experienced along the way.

Keywords: museum-based medical education, professional identity formation, multisensory learning, skill-based healthcare education

Introduction

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) and the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics at the McGovern Medical School, UTHealth have collaborated in offering an elective Art of Observation course since the early 1990s. The three-session course, offered in both fall and spring semesters, is designed for first- and second-year medical and dental students, and each two-hour session takes place in the museum’s galleries. Through close looking and active discussion, students in the early years of the course honed their observation skills by looking deeply at works of art, discussing what they could see with their classmates and facilitators, and drawing inferences that could inform their medical and diagnostic practices. Over the years, through the aegis of the museum’s longtime partner Rebecca Lunstroth, associate director, McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics, the course expanded scope to explore how discussion of art in the museum’s galleries could provide a safe space for addressing critical skills often absent from medical education, including understanding bias and practicing tolerance.

With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Art of Observation—which requires in-person participation—went on hiatus until the fall semester, 2021, when the course could resume at the museum with all participants wearing masks. Much had happened in the intervening months since the course was last offered. Students, professors, and museum staff had been learning and working remotely; they experienced the illness and death of patients, colleagues, and loved ones due to the pandemic; they witnessed the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd with ensuing protests against racism and injustice; and for many, their sense of wellbeing was scarred by these events. How could the organizers of the Art of Observation course create a learning environment for the medical and dental students commensurate with this challenging moment?

At the MFAH, one bright light amid these challenges was the opening of the new Nancy and Rich Kinder Building of modern and contemporary art in November 2020. The architecture designed by Steven Holl provided an immersive oasis to experience novel works of art, many themselves immersive installations. The Art of Observation course planning team decided to capitalize on this immersive environment to create opportunities for multisensory learning sessions that could provide students with an alternative learning experience, separate from the classroom, clinic, and outside world. To heighten this multisensory experience, the team reached out to colleagues at the Moores School of Music in the College of the Arts at the University of Houston to add learning sessions with music, which many consider the most immersive of art forms. With these ingredients, staff from all three Houston institutions codesigned multisensory learning modules in direct response to learning goals that would fill gaps in the standard curriculum for medical and dental students in their first and second years.

In this chapter, the collaborative team will share its experience codesigning new approaches and classroom experiences for this newly conceived Art of Observation course, and its implementation in the fall semester, 2021 and spring semester, 2022. The first section of the chapter will address the course itself, sharing experiments in building and executing the new curriculum. Each session will be discussed, beginning with the learning goal for each class period. Links to comments and assessments from two McGovern Medical School students will also be shared: Gavin Roland from the fall 2021 semester, and Samantha Oglesby from the spring 2022 semester. The second section of the chapter will focus on new approaches to pedagogy, the research and evaluation collected from students in the course, and challenges in planning and implementing the course among the three institutional partners in Houston.

Part One: Overview of the Three Art of Observation Sessions

During curriculum planning for the new version of the Art of Observation elective course, the team began by composing learning goals for each of the sessions and then workshopping those goals and possible exercises with educators at the MFAH, Jennifer Beradino and Emee Hendrickson, who became the primary facilitators of the discussions with the students.[1] Their work with the students was critical to the success of this re-envisioned course. The first learning goal of honing communication skills felt like a fundamental place to start, with skills that could be practiced throughout the course.

Session One: Communication

Communication is key to any successful relationship, but how do you guide learners in developing self-awareness around their own communicative strengths or weaknesses? Studies have shown that physicians interrupt their patients within seconds after they begin speaking. If one examines the many demands on a clinician’s attention, this may be a slightly easier statistic to digest. Hospital administrators often use metrics examining productivity to award clinicians with key academic promotions or merit raises. Trainees working under time-pressured clinicians quickly recognize the value in providing concise yet accurate patient presentations to their team. From salary increases to positive evaluations, or even the rare opportunity to sit down for lunch—in clinical medicine, efficiency and speed are constantly rewarded. An added challenge students encounter as they begin to create their professional identity in healthcare involves internalizing a new healthcare vocabulary, with an associated range of acronyms and jargon, that has the potential to create new barriers to meaningful patient communication. One intention behind this goal is to remind healthcare students of what patients may experience when they are immersed in an unfamiliar space, where the language or vernacular used may feel foreign.

Session One Learning Goal: Communication

Effective communication is essential for medical professionals in building productive relationships with patients, in fostering interdisciplinary collaboration with coworkers, in processing uncertainty and ambiguity, and in challenging personal and group biases. This session will offer tools for 1) understanding the importance of listening, 2) practicing verbal description of what can be observed, and 3) making inferences about what is observed. Effective communication will be a critical learning goal at the heart of each session in this course.

Each session of the Art of Observation elective comprised two related exercises, which built upon one another.

Exercise 1: String Quartet Communication Lab

To inspire reflection and conversation about effective communications strategies, the course organizing team presented UT medical and dental students with an opportunity to observe a string quartet rehearsing a piece of music together for the first time. This activity was premised on the notion that a string quartet faces communication challenges similar to those of a team of medical professionals. Like a team of doctors and nurses, a string quartet is comprised of individuals who have mastered a particular role. To create an optimal team performance, the quartet members must prepare and execute their individual parts with integrity and skill, while also flexibly adjusting to their collaborators’ needs and differing ideas.

Before meeting the string quartet, UT medical and dental students first convened in a museum classroom and spent time answering two questions in their journals:

- Remember a time when communicating with a teammate was a challenge. What made collaboration difficult?

- Do you have any techniques or strategies that you employ to communicate effectively with collaborators?

While the medical students journaled, the members of the University of Houston Tomatz graduate string quartet stationed themselves far apart from each other at various places on the first three floors of the MFAH’s Kinder Building and practiced independently their individual parts for Beethoven’s String Quartet Opus 18, no. 5, movement 3. The cacophonous sound of the unsynchronized players could be heard throughout the museum. After completing their journaling assignment, the medical students were instructed to walk through the museum, following the sound of each musician, until they arrived at the fourth player in the quartet, the cellist, located on the third floor of the museum.

Once everyone had arrived on the third floor, the quartet came together to rehearse and be observed, now as a team, playing the Beethoven excerpt together for the first time. To focus attention on the various elements of communication, the quartet divided their rehearsal into an unusual sequence of “communication experiments.” First, the quartet played through the Beethoven excerpt sitting back-to-back, so that the four players could not see each other. They attempted to play precisely together, simply by listening to each other. Next, they played the same music looking at each other, but without speaking. Finally, the quartet was allowed to speak as they normally would in a rehearsal, asking each other questions, making requests, and proposing ideas.

Following each “communication experiment,” a museum educator facilitated a conversation with the medical students, inviting them to share observations and questions. Here are three of the most interesting realizations about how the string quartet communicated well as a team:

- Just by looking at each other, the quartet was able to not only synchronize their work, but they also each seemed to perform with more confidence and expression. A face-to-face supportive interaction encouraged confidence.

- Sometimes spoken language was less effective when trying to share ideas. Often the quartet would sing to each other or physically demonstrate, and that created mutual understanding more quickly than spoken language.

- The quartet demonstrated a productive ability to receive constructive feedback from collaborators. A trusting attitude from all members meant that differing perspectives could be shared and creatively experimented, without any resentment or time-wasting defensiveness.

The medical students were able to apply some of these new communication strategies to situations that they may encounter with patients. As can be heard in the medical student responses embedded here, recorded at the Innovations in Arts and Health conference, Gavin Roland and Samantha Oglesby, both second-year students at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth, correlated the complexity of communication between physician and patient to the demonstration of communication skills the musicians had perfected.

Exercise 2: Back-to-Back Drawing

The curriculum team wanted to incorporate the back-to-back drawing exercise, which had been used in the Art of Observation course for many years, to have a tried-and-true anchor within this new curricular experiment. In many ways, the initial string quartet communication lab was designed to complement this exercise, so that through lines in the importance of listening and nonverbal communication could be perceived by the students as equally important to clear and respectful verbal communication.

This activity was adapted from standard communication and team-building exercises used in the workplace. The students are divided into pairs, with one dental and one medical student, when possible, understanding the benefits of cross-professional training. The students choose roles—either as speaker or drawer. They are assigned galleries with three-dimensional art objects—sculpture or decorative arts (clocks, vases, furniture), and those with the speaker roles choose objects that they would like to describe to their partners. They set up stools back-to back, so that the speaker is facing the art object and the drawer is looking in the opposite direction. The drawer is equipped with pencil and paper clipped to a board, and the speaker describes the work of art they are viewing as clearly as possible, so that their partner can draw it on their paper. The drawer listens and makes marks on the paper, guided by the speaker’s description—or their interpretation of what the speaker has said. The drawer can ask clarifying questions, to which the speaker responds, but the speaker cannot view their partner’s drawing. Once finished, the speaker and drawer reverse roles and choose another work of art to describe and draw.

As can be heard in the video below, the students were wary at first about having to draw. However, as they came to realize, the exercise is less about learning how to draw and more about honing skills in listening, patience, and clear verbal communication that respects the needs of the listener.

Relevance for Healthcare Education

Healthcare providers are encouraged to transition beyond the initial confines of a “beginner’s mind” with the aim of becoming a professional with some level of expertise. By placing students in activities that encourage a beginners mind approach, while letting go of the frenetic pace that is often inherently present within clinical encounters, students reacquaint themselves with a range of skills needed to foster effective communication and collaboration.

Patients want to be seen and heard. Successful clinicians recognize the many ways patients communicate their concerns or needs while also relaying regard and concern for patients, despite the other demands on the clinician’s attention. Healthcare professionals must also develop a heightened level of self-awareness to recognize how they can best navigate challenging situations, all the while conveying care and regard for their patient’s needs. By placing students in a safe space to practice and experience communicative successes and failures, these activities aim to provide opportunities for professional growth and self-awareness with an ultimate goal of optimizing patient care.

Session Two: Ambiguity and Uncertainty

In traditional healthcare education, the value of uncertainty and ambiguity are often passed over for more highly coveted accuracy and definitive conclusions. Many healthcare students are high-achieving individuals who are often accustomed to a level of success with academic challenges. However, much of clinical practice involves learning how to be comfortable in uncertain situations, where clear conclusions are not easily within reach. Providing learners an immersive, multisensory opportunity to safely navigate low-risk uncertain scenarios is a primary focus of this session. The goal of this learning objective is to foster professional identity formation through improved self-awareness, while also encouraging curiosity and innovative team-based problem solving amid activities and environments that can be somewhat unsettling.

Session Two Learning Goal: Ambiguity and Uncertainty

Ambiguity and uncertainty are constant realities in medical and dental clinical practice, and yet generally unacknowledged in medical education. Rather than risking a false sense of certainty by closing down an investigative process, this session will help build adaptive strategies for uncertainty, highlight the value of curiosity, and construct new frames of reference for investigation.

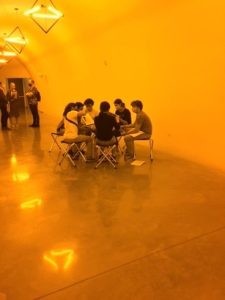

Olafur Eliasson Tunnel Experience

This activity responds to the immersive light installation by Olafur Eliasson, Sometimes an underground movement is an illuminated bridge, 2020, in the tunnel connecting the museum’s Glassell School of Art with the Kinder Building. In this installation, Eliasson designed angular light fixtures that hang from the ceiling, fitted with mono-frequency, low-pressure sodium lights. Their narrow-frequency band of yellow light fills the tunnel with a hazy yellow aura, which reduces the eye’s color perception to shades of yellow, gray, and black.

The MFAH planning team wanted to use Eliasson’s palpably immersive, disorienting space as an entry location for students to begin this session on coping with ambiguity and uncertainty. Within the safe space of the museum, the team wanted to create a set of experiences that increasingly frustrated students’ desire for certainty and clarity. At the outset, in the tunnel space, students were given a schedule for the day, which was playfully redacted, omitting key information from the session’s itinerary. They were then asked to form cross-professional teams of six and given an envelope to open as a group. Inside was a reproduction of an artwork on view in the Kinder Building; each team had a different image. The first task was to determine what was happening to their vision in this tunnel space, and next, to determine the actual appearance of the image in their envelope. What were the colors used in the original works of art, or was the image they were looking at originally created only in black and white? How could they arrive at their conclusions as a group, and what strategies would they use to determine missing information?

As the video below illustrates, students were truly baffled about how to draw conclusions in this activity. However, they appreciated having teammates to help them develop strategies for coping with uncertainty and making determinations, especially when their conclusions did not bear out when they viewed their images in natural light.

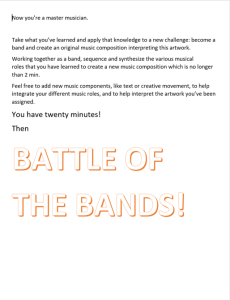

Battle of the Bands

Ambiguity and uncertainty are uncomfortable and scary. However, rushing to find relief though a false sense of certainty, without thorough inquiry, may lead to unproductive outcomes. A professional team can flourish in ambiguity if they open-mindedly rely on the diverse perspectives and creative ideas of each team member.

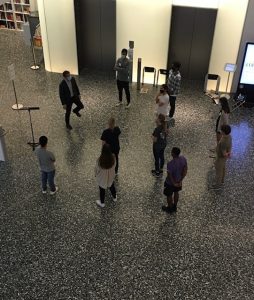

In the first session, UT medical and dental students observed an ensemble of musicians making music. In the second session, these students were challenged to create their own music, by applying what they learned about effective communication as a team. To begin the activity, the medical students were divided into three “specialist” groups that relocated to separate corners of the Kinder Building. They were not told any details about the project they would be expected to complete or anything about the other specialist groups. Once separate, a University of Houston music pedagogy graduate student taught group one to hum a very specific melody, while a different UH music teacher taught group two how to create a musical pulse by clapping and stomping. Group three learned to create a variety of expressive audio effects with their mouths and hands. After each group had completed their specific music skill class, the medical students were asked to explore the museum and find the artwork with their original team from the Eliasson tunnel activity that opened the session. Only when these original groups were reunited and looking at their artworks in the galleries was the final assignment of the evening revealed: a Battle of the Bands. The students were asked to create an original performance that would interpret their artwork and incorporate the three specialized skills learned in the previous music classes.

The experience was uncomfortable by design. The idea of performing originally composed music for others was scary for most of the students. The steps of the process were unclear, complicated, and even seemed ridiculous. The expectations and criteria for success were never plainly articulated.

The Battle of the Bands was ultimately a very uplifting, affirmational creative experience. Each “band” of students created wonderfully unique performances, tackling the ambiguous challenge of interpreting visual art through music with wit, imagination, and supportive collaboration. The skills acquired from the UH music teachers surfaced in the performances in unexpected ways, but more importantly, the groups devised new methods for musical expression, including inventing instruments from gallery chairs and pencils, composing chants from gallery labels, and choregraphing movements to clarify the meaning of the music. How these innovations occurred was revealed in a group discussion at the end of the evening. The students recounted how the unclear instructions and expectations pushed each team member to venture further outside their own comfort zones. Group members, embracing the ambiguity, began to suggest novel ideas to accomplish the goal. In some groups, team members who typically resist leadership roles, found themselves guiding the ideas of the group. The ambiguity of the challenge invited creativity, open-mindedness, and trusting collaboration. The students who participated in the Innovations in Arts and Health conference bore this out in their responses to this session.

Embed medical student responses in video, 27:14 to 29:28

Relevance for Healthcare Education

These activities challenge learners to sit with discomfort and uncertainty and offer opportunities to develop self-awareness of how to move forward in spite of these hurdles. Similar to uncertainty in healthcare practice, students chose to remain open to the possibility of what can come about by leaning on each other. In other instances, learners attempted to ground their approach to ambiguity by finding an entry point of familiarity. In clinical practice, these strategies are the foundation to navigating complex cases. In addition, how you “feel” as a provider when faced with uncertainty is not a question commonly explored in healthcare settings. However, healthcare students within the museum quickly articulated their discomfort or disorientation and discovered that, in sharing and validating these concerns, they were able to create a level of transparency with each other. Lowering these walls and creating a more transparent environment allowed students to move forward together and successfully tackle the challenge in front of them.

Session Three: Bias

Unconscious bias is increasingly recognized as a key variable in healthcare inequities and is often a focus of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives across healthcare institutions. However, initiating and facilitating conversations around racism in healthcare can be a difficult task. For healthcare students who are just beginning the process of developing a professional identity, surfacing biases and developing self-awareness around one’s own blind spots or unconscious thought processes are key first steps in addressing unconscious biases. By placing this session at the end of the course, the curriculum team hopes learners have already experienced the museum galleries as a safe space for difficult and vulnerable conversations. It is rare for healthcare students or professionals to be asked about strong negative opinions or experiences.

The main intention in creating a session focused on biases around art is to support students’ abilities to surface and identify other personal biases they may hold as they move beyond this course and further into their professional training. We wanted to also draw a clear connection to empathy and how one can find meaningful connections with those they may disagree with or have negative emotions toward.

Session Three Learning Goal: Bias

Unconscious bias has been identified as one of the contributing causes of unjust disparities in healthcare. The final session of this course uses the safe space of the museum’s galleries to explore participants’ patterns of perception and preference, to identify triggers of negativity, and to build capacity for empathy and generosity. Improved self-awareness to foster professional identity formation serves as a primary goal of this session.

Negative Response Exercise

This exercise is the first of a two-part session, with the first part focused on uncovering unconscious bias and the second on moving from bias toward empathy. This “negative response” exercise was inspired by a workshop at the Art of Examination: Art Museum and Medical School Partnerships Forum, organized by the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History and hosted at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in June 2016 (Pittman 2016). Participants in the workshop—museum educators and medical professionals—gathered in one gallery at MoMA. The facilitator asked them to find a work of art in the space to which they had an immediately negative response to the point of real discomfort. Then participants were asked to describe why they reacted so negatively. It was an utterly disarming and revealing experience. For example, when Caroline Goeser, coauthor of this chapter and attendee at the Art of Examination forum, admitted she had a vehement aversion to the work of a specific artist, the medical professionals in the room found this admission a welcome surprise. It allowed them to think differently about museum educators and museum spaces, and to feel less inhibited about revealing their own assumptions and biases.

In Houston, this same exercise opened the final course session, in an effort to begin to uncover participants’ unconscious biases. As Samantha Oglesby mentions in the embedded video segment, it was particularly enlightening for her to hear multiple responses to the same object she disliked—to hear new perspectives that countered her own.

Embed medical student response from video: 35:15 to 36:44.

Empathy Lab

The final activity of the final session of the course was designed to invite the students to fully enjoy an emersion into the museum and its rich variety of art. After two busy sessions of highly interactive experiences, the culminating activity of the course simply asked the students to wander, discover, reflect, and relate their own perspectives, histories, and relationships. This final activity aspired to make individual encounters with artworks into an opportunity to find empathy for others.

The “Empathy Lab” began with a journaling session. The medical students were instructed to identify and describe people they personally knew that matched the following profiles: someone who misunderstands me; someone who doesn’t listen; someone who can do no wrong; someone I’m worried about; someone who inspires me. After completing this journal assignment, the medical students were instructed to once again wander the museum in search of artworks. In contrast to the first activity, the medical students were now looking for artworks that they might give as a gift to each of the people that they wrote about in their journals. These gifted artworks should be chosen in a spirit of empathy. The gifts should not be chosen to teach the receiver a lesson or to express some unheard feeling from the gift giver. Instead, the artworks should help the gift giver express and demonstrate their desire to empathize with the person who misunderstands them, who doesn’t listen, or who can do no wrong.

After an extended opportunity to wander independently looking for gifts, the medical students convened for a final conversation about their experiences. Students shared what they found in the museum and why certain works helped them relate to someone they knew. Through sharing, the students also discovered that within their group there were a variety of common experiences but also unique perspectives and hardships. The exercise became an opportunity for the students to confront their differences thoughtfully, without consequences, because art interpretation was a mediator.

Relevance for Healthcare Education

Asking students to share negative responses validates emotions that are universal but not often asked about in a professional context. We found it often takes one student to discuss the art they feel strong dislike toward for others to then share similar “negative” sentiments. Students in high-stress environments, like medical school, can experience pressure to be “on” and demonstrate the highest levels of professionalism at all times. Regular debriefs led by museum educators and clinical faculty are key to providing both structure and a framework for why negative emotions around art can serve as a starting point to think about other biases around race, gender, or other aspects of identity that can complicate interactions with others. By bridging this activity to one that centers around empathy (the gift-giving exercise), the team hopes to emphasize the importance of finding commonality despite any negative emotions and that this may be an active process at times. In healthcare, clinicians will be tasked with caring for patients who they may not share commonalities with or with patients who may direct negative emotions to their healthcare providers. Finding empathy within these types of challenging interactions can be a difficult skill but one that is required for those who choose to pursue careers in the healthcare profession.

As medical student Gavin Roland concluded at the end of the conference panel, the debriefs at the end of each activity and session, and at the conclusion of the course, were critical in summing up, as he put it, the importance of “time, communication, and permission” to hone skills critical to healthcare practice.

Embed medical student response from video, 39:58 to 40:30

Part Two: Pedagogy, Research, and Challenges

Pedagogy

The institutional collaboration in Houston among the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics at UTHealth, the University of Houston Moores School of Music, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston is unusual among museum-based learning programs for health professions students. Most are partnerships between medical education institutions and art museums alone.[2] Not only are the students in this iteration of Houston’s Art of Observation course part of a cross-professional medical and dental cohort, a practice recognized as advantageous for healthcare professions training, they are also exposed to multisensory experiences across the visual arts and music.

What is valuable about experiential, multisensory learning in this context? Broadly speaking, the advantages of experiential learning in higher education have been studied and practiced by those who advocate for “object-based learning,” which Helen Chatterjee defines as “a mode of education which involves the active integration of objects into the learning environment” (Chatterjee 2015, 1). It promotes an experiential investigation and discovery process on the part of the learner, rather than a passive consumption of knowledge, understanding that “learning is enhanced when there is physical, emotional, and cognitive engagement” (Chatterjee 2015, 5). Liliana Milkova has further commented on the value of museum partnerships for students in higher education, normally confined to the university classroom. Immersion in the new learning space of the museum for both professors and students can “upend the traditional expert-novice framework which defines the classroom” (Volk and Milkova 2012, 96). Studies also suggest that students better retain information and memories through multisensory learning, especially if the learning has taken place across multiple senses, such as sight and sound (Levant and Pascual-Leone 2014, xvii; Ward 2014, 273-274).

Because the Art of Observation course aims to fill gaps in medical education, including honing skills like communication and empathy that will benefit health professionals’ engagement with their patients and ultimately improve patient care, the multisensory aspects of the course sessions are designed to disrupt the normative medical education classroom. Using the safe space of the museum, healthcare students can explore issues that are of deep concern for them yet unaddressed in the classroom, such as coping with the vast uncertainties they face in making diagnoses and determining patient care. Coping mechanisms for these issues can be explored through multisensory learning experiences, which have the potential for ready retrieval down the road in their clinical experience.

This course is grounded in several key museum-based approaches to medical education. One construct, which Liz Gaufberg refers to as the “third thing in medical education,” builds on a framework described by educator Parker Palmer (Gaufberg and Batalden 2007). By approaching self-reflection through objects in the museum, and not through the voice of the facilitator or student, participants have a way to share about the objects using metaphor. Learners are afforded space to share insights through their own personal lens, with the flexibility to share as little or as much as they feel comfortable. When we approach truth “on the slant,” Parker notes that the shy soul is given the protective cover it may need.

In addition, learners are shown ways to make “thinking visible” using Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) and related museum-based educational approaches. VTS, an arts-based pedagogy, has been shown to support teaching of observation skills, observing nuance, critical thinking, professionalism, and humanism (Chisolm, Kelly-Hedrick, and Wright 2021). By encouraging students to share their assumptions and interpretations around art while placing priority and value in revising misinterpretations fostered through perspectives provided from peers, tenets of shared decision making and limiting biases are fostered. These critical skills, required of any healthcare professional, are difficult to achieve within a healthcare education system that prioritizes accuracy and efficiency.

Research

Pre- and Post-Test Findings

During the 2021-22 academic year, the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics conducted a pre-post educational research study with medical and dental students to evaluate the impacts of the Art of Observation elective. One portion of this study will be shared here, including several open-ended questions about personal biases. Students were asked to define “personal bias” and name some ways in which personal biases can affect individuals’ judgment, among additional questions. Responses were first coded into categories to allow for describing and identifying common answers. The responses were then coded thematically for broader interpretations of participants’ shared or common views around personal biases.

With defining personal bias, participants’ definitions shifted from the pre- to post-survey. Namely, in the pre-survey, they responded that personal biases were related to past experiences (12.5%), generalizations or stereotypes about people (5.6%), or were based on preferences (4.2%), judgments (4.2%), and prejudice (4.2%). These ideas shifted in the post-survey, in that students connected personal biases more so with past experiences (14.3%), individual beliefs or opinions (8.6%), influenced by personal background and upbringing (8.6%), cultural backgrounds (5.7%), individuals’ environments (5.7%), and their worldviews (5.7%).

Similarly, when asked to consider how personal biases affect one’s judgement, in the pre-survey students most often mentioned that personal biases affect how one treats or thinks about others (9.6%). However, in the post-survey students more frequently answered that personal biases facilitate making incorrect assumptions or conclusions (13.3%) and keep them closed off from others’ perspectives (10%).

Results showed that although students expressed some understanding of personal biases before the course started, upon completion of the program their understanding of personal biases appears more nuanced and complex. In particular, when thinking about the shift in how biases affect one’s judgment, learners pivoted from a general construct of how one treats or thinks about others to a more specific focus of creating incorrect assumptions or conclusions about someone and not being receptive to the perspectives of others.

Student Course Evaluations

The MFAH administered a student course evaluation through Survey Monkey for both the fall 2021 and spring 2022 sessions. The open responses to the penultimate question, “What was most surprising about your experience?” were perhaps the most revealing. The most frequent response was the element of music, especially the initial string quartet activity. Students found the experience of walking through the museum and hearing the music “frankly beautiful and extremely memorable,” as one wrote, or “shocking and beautiful,” in the words of another. Others said it reminded them of how much they “missed the arts” and “being creative.” One expressed their surprise at being able to practice different art forms, from drawing, to music, to writing in their journals.

Many expressed how surprised and appreciative they were about the interactive, immersive, and experiential learning, and they liked connecting across professions to students they did not know, and deepening relationships with students they already knew. Many were also surprised at “how directly art could be used” to concretize skill-based learning in the medical field, and at “the similarities one could draw between art and medicine.” One student mentioned how different these arts experiences were from their medical education but surprisingly applicable.

In assessing each of the three sessions, many found the first on communication their favorite, especially the back-to-back drawing exercise, which allowed them to assess their own styles of communication in new ways. While most found the second session very uncomfortable and challenging, they also liked having to cope with their feelings of uncertainty in the safe space of the museum and in collaboration with fellow students. For some, the third session on uncovering bias was the least effective, with fewer opportunities than desired to debrief in small groups, while others really liked the opportunity to express their own negative feelings with the larger group and to imagine giving gifts to those who they were concerned about or who they felt did not understand them. Through this activity, one student discovered, “I misunderstood the person who did not understand me.”

Challenges

It was both a dream and a challenge for the cross-institutional planning team to create space for re-envisioning the Art of Observation course for medical and dental students as an experiment in immersive, experiential learning across the visual arts and music. The team developed many new approaches and activities in reorienting the course, as well as keeping a couple of popular visual arts activities as mainstays that would bridge back to earlier course offerings. With the addition of music in the curriculum came added logistical planning for integrating musicians and music educators into the course. As a result, the fall 2021 offering of the revised course was complex, with many pieces and parts. In response, the team had the opportunity to edit the spring 2022 offering, paring it down to the two activities per session that are discussed in this chapter.

Pedagogically, the revised course planning was a valuable learning experience, especially for the educators in music and the visual arts. It provided a new opportunity to hone the purpose and approach of art education in the service of healthcare educational goals. For this project, the team abandoned the idea that works of art or music might teach healthcare students something specific about the art or music’s form, materiality, or history. Instead, the aim was to engage with art in the museum through hands-on drawing, music performance, and music-making to incite conversations. It was through safely organized, thoughtful dialogue about art and creative experiences that the emerging healthcare professionals learned strategies for changing their perspectives, sharing insights, and ultimately becoming more communicative, courageous, and empathetic.

Coordinating schedules and optimizing availability for both dental and medical students can pose logistic challenges. Students across two professional schools and within every academic year can potentially participate in the course. As a result, students often express some level of distress initially when exams are also scheduled during one of the museum-based sessions. Although this may seem like a barrier to engagement, many students recognize and view the time in the museum as restorative, with some students reframing their participation in the course as a break from the rigors of studying and not a deterrent from preparing for upcoming exams. As it is currently formatted, this course is an elective for medical and dental students. Although one lecture emphasizing the importance of close observation using visual art is incorporated into the core curriculum for first-year medical students, a more integrated approach to this course and the key concepts discussed should be required for all students. One could argue that the students most in need of the content in this course may never opt in and miss the unique opportunity to support their self-awareness and professional identity using a museum-based approach.

Conclusion

The value of re-envisioning this course has already had multiple benefits—perhaps most importantly, creating a curriculum based directly on learning goals designed to benefit the healthcare students, especially in filling gaps in their core medical education coursework. Utilizing the immersive nature of the new MFAH Kinder Building architecture and art installations, the team has been able to surprise students with multisensory, experiential learning that allows them a completely alternative learning environment, which is nonetheless applicable to their emerging healthcare practice and professional identity formation.

In creating this new experiment across the visual arts and music, the organizers of the course realized that having access to the galleries during the evenings the MFAH was closed was critical for success. Previously, the course had been offered on Thursday evenings, when the galleries were open to the public and often crowded. This was never ideal for student groups, but with the addition of music in the galleries, it felt like the right time to make this shift. No matter how this course moves forward, that shift will remain. It has been absolutely magical for the students and facilitators to have the museum to themselves, creating a truly safe space for exploration.

There are several ways in which this three-way collaboration can move forward. Because the team is still orienting themselves to the new curriculum, honing the balance of music and visual art is an ongoing process. The planning team has begun to think about the kind of music that is explored in the initial communication exercise, which has worked so beautifully with the classical string quartet. Another possibility, however, is to work with jazz musicians and the art of improvisation. This may provide a new window for the students onto the value of nonverbal, responsive communication. The team has also imagined the possibility of integrating a third artistic form, the dramatic arts or applied theater, into the course. This would allow an expanded collaboration with the University of Houston College of the Arts, and a further, perhaps even more interactive, opportunity for students to creatively participate and learn.

The team has been pleased with the positive research findings and student evaluations and wants to be responsive to suggestions for improvement. The course size is fairly large, with 30 to 35 students. Several evaluations suggested that smaller facilitated debrief sessions would allow more students a safer space to share their responses. Because these discussions are critical in making applications from the space of the museum to the students’ coursework, clinical practice, and professional identity formation, the team wants to make every effort to allow each student to participate.

As a stand-alone elective, this three-session course has a total of just six hours of contact time with first- and second-year healthcare students. Therefore, the pre- and post-test research and student course evaluations can reveal only partial conclusions, especially when assessing the long-term effects on professional identity formation and quality of patient care. Perhaps there could be continued opportunities for the students to check in with the facilitating teams of this course at points in their medical school trajectory, or drop-in refresher sessions at the museum to reinforce lessons learned and to collect further evaluation and research. Ultimately, if repeated sessions like these were required and more fully integrated over several critical points in medical school coursework and clinical practice, the long-term effects could be more accurately assessed.

References

Chatterjee, Helen, et al. 2015. An introduction to object-based learning and multisensory engagement. In Engaging the senses: Object-based learning in higher education, ed. Helen Chatterjee and Leonie Hannan, 1. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Chisolm, M., M. Kelly-Hedrick, and S. Wright. 2021. How visual arts-based education can promote clinical excellence. Academic Medicine 96(8): 1100-1104. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003862

Gaufberg, E., and M. Batalden. 2007. The third thing in medical education. The Clinical Teacher 4: 78-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2007.00151.x

Levant, Nina, and Alvaro Pascual-Leone. Introduction. In The multisensory museum: Cross-disciplinary perspectives on touch, smell, memory, and space, ed. Nina Levant and Alvaro Pascual-Leone, xvii. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Pittman, Bonnie. 2016. The art of examination: Art museum and medical school partnerships forum report. Dallas: Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History, University of Texas, Dallas, October 2016. https://arthistory.utdallas.edu/medicine/forum

Volk, Steven, and Liliana Milkova. 2012. Crossing the street pedagogy: Using college art museums to leverage significant learning across the campus. In A handbook for academic museums: exhibitions and education, ed. Stephanie Jandl and Mark Gold, 96. Edinburgh and Boston: Museumsetc.

Ward, Jamie. Multisensory memories: How richer experiences facilitate remembering. In The multisensory museum: Cross-disciplinary perspectives on touch, smell, memory, and space, ed. Nina Levant and Alvaro Pascual-Leone, 273-274. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Jenifer Beradino, senior manager, object-based learning, and Emee Hendrickson, object-based learning specialist, Department of Learning and Interpretation, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ↵

- The Edith O'Donnell Institute of Art History at the University of Texas, Dallas, maintains a listing of courses offered by art museums and medical education institutions in partnership. ↵