Collaborative Projects in Narrative Medicine and the Visual Arts at the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics at McGovern Medical School

Megan G. Jiao; Sarah Syed; Anson Koshy; and Renee Flores

https://doi.org/10.52713/YODR5791

Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of new opportunities for medical students, residents, faculty, and others to gain depth and insight into illness and suffering by exploring connections between arts and health. While all medical students have formal humanities exposure, there are extracurricular opportunities to explore healthcare and engage in reflective practice through art, media, poetry, literature, music, and writing. These activities enrich medical education, training, and practice, promoting ethics, professionalism, compassion, empathy, and resilience. This chapter describes a range of initiatives at the intersections of arts and health, including faculty writing workshops, student-led narrative medicine programs, and collaborations with local artists.

Keywords: arts, humanities, medical education, reflection, narrative medicine, physician-patient relationships

Introduction

Significant collaborative efforts have been made to integrate the arts and humanities into medical education, fostering enhanced empathy, teamwork, communication skills, and humanistic sensibility among medical students and trainees. By extension, the arts and humanities have become increasingly recognized for their role in promoting professional identity formation in medicine. Physician Molly Cooke and colleagues define this concept as “the development of professional values, actions, and aspiration” and denoted it the “backbone of medical education” in Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency (2010). Today, the Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education (FRAHME), an initiative of the Association of American Medical Colleges, affirms that the arts and humanities are more than “joys and pleasures”—the health professions are leveraging them as an evidence-based approach to develop trainees’ and physicians’ professionalism, ethics, compassion, and resilience.

Founded in 2004 at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics is dedicated to teaching and scholarship that examines the context and experience of medicine and healthcare. The McGovern Center provides substantial health humanities programming for students and trainees in the health professions. These include a Medical Humanities Scholarly Concentration for medical students, a clinical humanities certificate for dental students, and a new humanities program for graduate medical education trainees. Beyond its broad curricular programming, the McGovern Center plays a considerable role in facilitating the creation, development, and maintenance of several initiatives led by students and faculty. This chapter presents a synopsis of some recent endeavors by faculty and students at the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics to assimilate various aspects of the arts and humanities into medical education. Each section provides a distinct model of applying medical humanities into practice, incorporating various humanistic topics and audiences that range from students to faculty and beyond.

In the first section of this chapter, geriatrician Renee Flores describes her writing group experiences at a faculty level within her department. She delves into the personal and professional growth that arose from the reflective writing process. These experiences at the faculty level inspired additional endeavors by both students and faculty aimed at broader audiences, which will be highlighted in the subsequent segments of the chapter.

In the second section, Megan Jiao, a second-year medical student in the Medical Humanities Scholarly Concentration at the time, describes how she built upon her undergraduate experiences with narrative medicine at Duke University to create an event series for McGovern Medical School in collaboration with Renee Flores. This narrative medicine-based initiative aimed to bring students and faculty together in conversation about important topics in medicine and cultivate community by exploring literature, poetry, art, and other audiovisual media.

In the third section, Sarah Syed, then a fourth-year medical student, recounts her experience producing a narrative medicine and reflection workshop series under the mentorship of Renee Flores to meet requirements for the Medical Education Scholarly Concentration, another scholarly track at McGovern Medical School. This concentration aims to enhance students’ academic and professional development by engaging them in creating an interdisciplinary health-related project to improve medical education. Syed’s narrative medicine initiative engaged medical students in their clinical years with a structured curriculum, teaching activities, and assessment developments.

In the final section, pediatrician Anson Koshy outlines the development of visual arts opportunities through collaborations among the McGovern Center, students, and local artists. He describes his work producing the Human Ties Digest, a digital journal that provides an institution-wide platform for poetry, prose, photos, and other media. Koshy also details his collaboration with Houston-based artists for the Arts and Resilience lecture series, which serves as a platform for local professional artists to share their work with healthcare professionals.

Even though these initiatives differ by content and audience, they were driven by a shared goal of integrating the arts and humanities into medical education. This chapter aims to demonstrate how the medical humanities may take on varied permutations in practice through reflective writing, literary and media analysis, and visual art. However, regardless of their specific form, they play an integral role in medical education for their critical engagement with varied aspects of the human experience.

Faculty Writing Group

Renee Flores

In 2018, a small group of five physicians affiliated with the Joan and Stanford Alexander Division of Geriatric and Palliative Medicine at McGovern Medical School dedicated themselves to regular writing as part of their journeys of lifelong learning. Intending to align with the core values of the medical school for scholarship and innovation, we invited Thomas Cole, the founding director of the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics. With Cole as our support and leader, we also promoted interprofessional collaboration by inviting Anson Koshy, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician, to participate in our small group.

We would meet monthly at the medical school. Cole would choose a writing prompt ahead of time and send it via email before our meeting. We would independently read the prompt on the honor system and write for ten minutes. On the day of our meeting, we would bring our writing unedited. The journey of reflection through writing within our group was new. This process of self-discovery and exploration through writing brought a new skill to our physician group that we explored in a group setting. The tangible piece included sharing our writing, which brought value to the self-expression of these carefully selected prompts. Sharing our deepest thoughts and ideas, expressions, feelings, and experiences unraveled dynamics well-documented in research yet relatively unknown and unexplored in our academic circle. Our creative outlet for revealing ourselves and our writing in a safe space led to close listening and compassion for ourselves, our group members, colleagues, and patients. When the pandemic arrived, our in-person meetings turned to a virtual format, and we continued to explore with depth driven by circumstance. Our families, fear, death and dying, and professional constraints guided our paths for self-exploration and discovery. It also created a safe space, community, and strength in interacting with the world of uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the writing process, reflecting changed our perspectives on the value of our group and monthly writing sessions. Our small group practices then expanded to a faculty development workshop led by Thomas Cole and me. The workshop was a one-hour breakout session for professional development for all clinical faculty within the Internal Medicine Department at McGovern Medical School. The workshop followed a format similar to our small writing group, which started with reading, close listening, reflection, and a writing prompt, followed by sharing and further reflection. The gratification derived from the community, alongside personal and professional growth, prompted us to lead workshops beyond the institution to disseminate our reflections and experiences. We also took part in a few conferences regionally and nationally, extending the value of our experiences beyond the Houston area. Ultimately, lessons learned from these faculty writing groups inspired teaching modes and methods in other initiatives for the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics, including the narrative medicine-based initiatives in the following two sections.

Narratives of Illness and Healing: A Student-Faculty Collaboration in Narrative Medicine

Megan Jiao

Origins

Narratives of Illness and Healing is a monthly, narrative medicine-based event series that I conceptualized during my first year at McGovern Medical School and implemented in the fall of 2021 during my second year. Because I began medical school during the height of the pandemic in 2020, I wanted to establish meaningful student-faculty relationships, become acquainted with other medical humanities-oriented members of the McGovern community, and promote communal healing through the arts during a time of uncertainty and social isolation. I decided to pilot an event series inspired by my narrative medicine experiences at my undergraduate institution, Duke University.

In college, narrative medicine was my gateway to exploring the broader world of the medical humanities. I participated regularly in a monthly event series called Narrative Medicine Mondays, run by Duke’s Health Humanities Lab (Image 1). These events brought together undergraduates, graduate students, physicians, and liberal arts faculty to discuss short pieces of literature, poetry, and media, with occasional writing exercises. Works we discussed were only revealed during the meetings, so this cultivated a space of shared learning that broke down hierarchical barriers and enabled authentic connection. Participants could come as they were without expectations of prior reading or knowledge.

Image 1: A Narrative Medicine Mondays gathering.

Inspired by Narrative Medicine Mondays, I created and taught a semester-long seminar course for Duke undergraduates titled Narratives of Illness and Healing, a name I also adopted for the monthly event series at McGovern. (For clarity, any mention of Narratives of Illness and Healing for the remainder of this section refers to the McGovern initiative.)

To create the event series at McGovern, I combined the format of Narrative Medicine Mondays with the curriculum of my seminar course and drafted a proposal for review by the McGovern Center. While spending my first year of medical school in physical isolation, I noticed a widespread stagnancy in my peers’ and my own social networks and acute feelings of unease and lack of belonging. The inherently tumultuous nature of the first year of medical school was compounded by the psychosocial distress from the pandemic and near-total virtual learning. Therefore, I emphasized that the events should be open to anyone to cultivate a sense of community and interpersonal connection that the pandemic obstructed—students, residents, faculty, and staff at McGovern were all welcome. I especially encouraged attendance from preclinical students, who had not yet undergone clinical rotations. As a preclinical student myself at the time, I felt that we were most susceptible to crises of meaning while learning a substantial amount of medical material in the classroom divorced from real patient encounters, which were limited until clinical years. I believed personable, early encounters with faculty and staff at McGovern through the events would encourage a greater sense of belonging among students, stave off burnout, and possibly even pave the way for mentorship. After the events were approved, I connected with Renee Flores, a geriatrician and faculty member of the McGovern Center with a primary interest in narrative medicine, and Sarah Syed, then a fellow student who was planning a reflective writing workshop series for students in their clinical years. We brainstormed how our initiatives could overlap and ways to hold joint sessions. We also identified differentiating characteristics unique to our initiatives to ensure we were not mirroring each other too closely if students would like to participate in both. As we planned and eventually started running our events for the first time, we shared resources with each other and collaborated closely. We considered ourselves part of a novel narrative medicine program at McGovern Medical School, which had always had robust curricular representation of the medical humanities and ethics due to the presence of the McGovern Center but had fewer extracurricular opportunities tailored towards narrative analysis, discussion, and writing.

Narrative Medicine in Novel Contexts

Though the medical humanities have long contained precedents for narrative medicine, Rita Charon, a physician at Columbia University, coined the phrase “narrative competence,” which she described as involving “the ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others” (Charon, 2001). Medicine practiced with narrative competence was denoted “narrative medicine,” for which Charon outlined four objectives as an approach for more empathetic and effective patient care: “With narrative competence, physicians can reach and join their patients in illness, recognize their journeys through medicine, acknowledge kinship with and duties toward other health care professionals, and inaugurate consequential discourse with the public about health care.”

Since its inception, narrative medicine has developed into a global phenomenon. It has been adopted into medical school coursework, standalone workshops, educational programming for clinicians, and graduate degrees. Perhaps most prominently, Columbia University offers regular narrative medicine rounds (monthly events featuring guest lecturers or performers) and semiannual workshops led by Rita Charon, which are available to the public. As of 2022, 80% of medical schools in the United States were found to teach the medical humanities (not including ethics) in some capacity, and 32% incorporated literature or narrative medicine, which was the most popular specific branch of medical humanities represented (Howick et al. 2022). Much of the power of narrative medicine lies in its accessibility; it does not require a significant amount of clinical expertise to understand health narratives, nor does it necessitate a background in the humanities or literature to understand the texts used to spark discussion.

What makes narrative medicine initiatives distinct across institutions is often their structure and audience. Narrative medicine workshops are often open to an audience of patients, interprofessional healthcare workers, and other caregivers; however, at McGovern, we planned ours specifically for medical students, faculty, and staff to build community between trainees, physicians with established careers, and staff who played more indirect roles in student education. I wanted to ensure the event series emphasized student-faculty and student-staff connections because I believed that students could benefit greatly from the clinical and professional insights faculty and staff offered. Additionally, given the limited classroom interactions between faculty/staff and students (typically, most faculty/staff instructors would lecture to students only once or twice in the preclinical curriculum, and staff in administrative roles would interact with students even more rarely), I believed faculty and staff could also gain valuable perspective from students early in their medical training. Therefore, Renee Flores joined as the leading faculty facilitator to co-facilitate the sessions with me. I would serve as the leading student facilitator, and we would work together on every session to finalize materials and discussion topics. Flores would advertise the events through faculty-specific outlets, and I would do the same for students and the broader McGovern community. We also invited guest facilitators on topics and pieces of their choice to promote further engagement with our audience, and we ultimately hosted multiple guest sessions within the first year.

Another aim I had for Narratives of Illness and Healing was to present a wide variety of health-related narratives represented in visual and interactive media in equal amount to traditional, text-based sources. These media included graphic novels, short films, animations, and documentaries. Most novel of these were video games, a medium of great interest to me for its thriving indie scene that produces works unafraid to tackle challenging topics, such as mortality and mental health. Whenever possible, I included multimedia works during sessions to demonstrate nuanced differences in storytelling across texts and visual or interactive media and appeal to a variety of audience members’ interests. For example, I included excerpts about performing empathy in standardized patient experiences from Leslie Jamison’s essay collection The Empathy Exams and Corinne Botz’s short film Bedside Manner for a session called “Becoming a Doctor: Experiences in Medical Education.” For another event on graphic medicine and visual media, we analyzed scenes from That Dragon, Cancer, an autobiographical video game made by a father whose infant son was diagnosed with cancer (Image 2), as well as Stitches, a graphic memoir by David Small about his turbulent family dynamics and childhood experiences with illness. As a final example, I asked participants in a session on power and conflict to watch an interview by surgeon and writer Richard Selzer on his piece “Brute.”

Image 2: That Dragon, Cancer by Numinous Games.

Project Reception, Impact, and Looking to the Future

In my initial proposal for Narratives of Illness and Healing, I specified five objectives that I hoped the initiative would accomplish for attendees:

- Engage with important themes in medicine through discussion of literary texts and audiovisual media.

- Explore the role of storytelling and narratives in health-related contexts and our everyday lives.

- Develop a nuanced understanding of the ambiguity and complexity of health experiences.

- Cultivate our empathic abilities by reflecting on our connections with the texts and with other participants.

- Promote student-faculty connections and foster community at McGovern by bringing together students and faculty in conversation about shared topics.

The goal was to encourage participants to not only think critically about the presented health narratives but also utilize them as conduits to explore and better understand their own experiences, perspectives, and emotions. I hoped participants would engage with this process of internal discovery both in the moment through reflective discussions and for the longer term through the formation of a close-knit narrative medicine community at McGovern.

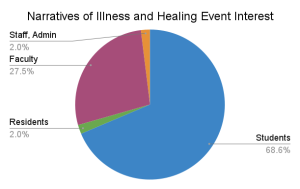

When I first advertised the initiative to all of McGovern Medical School, I received many interested responses requesting to be notified of upcoming events through the event email list. Initially, I received 76 responses, which grew to 102 by the end of the year. Across all responses, about 70% were from students across all four years, and the remainder were from faculty, staff, residents, and fellows (Image 3). Almost 60% of them expressed interest in serving as guest facilitators. These responses indicated to me that several members of the McGovern community had topics they were interested in sharing with others through discussions on meaningful pieces, or at least were like-minded in wanting to help contribute to building student-faculty connections through narrative medicine. Each session had an average of 15 to 20 attendees.

Image 3: Pie graph of interested responses demonstrating the distribution of students, residents, faculty, staff, and administrators.

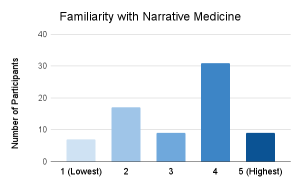

Post-session surveys evaluated participants’ familiarity with narrative medicine, the structure of the session (e.g., length, participant numbers), experience with the session (e.g., comfort level speaking up, the relevance of included pieces, enjoyment of having both faculty and students), and how well the session achieved the five outlined objectives. Based on 73 responses, attendees varied greatly in their familiarity with narrative medicine (Image 4).

Image 4: Bar graph of post-session survey showing variation in familiarity with narrative medicine among respondents.

Overwhelmingly, respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that the series was meaningful (96%), relevant (97%), and successful in achieving its objectives (99%, averaged across all objectives). 100% of respondents strongly agreed that sessions were thought-provoking and that they enjoyed having a mixture of students and faculty in the group.

Beyond quantitative data collected from a collective pool of participants, I received narrative feedback in the surveys. Out of 24 narrative comments, 67% included positively coded words ranging from generic (e.g., “Great session!”) to specific. Some of the specific comments reflected on what the session topic inspired them to consider in their clinical and personal lives, and others evaluated the impact of the session. For example, one student participant felt that “the session was trying to help me reflect as a person in addition to a clinician.” A faculty participant stated that their session “exemplified all of the benefits of the medical humanities,” and another mentioned that they “appreciate[d] these sessions and activities SO MUCH … they are so important” in response to a session on power and conflict in medicine. The remaining comments were either suggestions for improving the structure of the sessions (e.g., having reflective writing sessions between discussing pieces rather than at the end) or requests to have future sessions in person.

Aside from participants, I also received positive feedback from guest facilitators about their experiences. For example, two faculty members and one resident in psychiatry led a joint session on the life and works of Abraham Verghese, a prominent physician-writer. The opportunity to facilitate a guest session was particularly significant for one of the faculty facilitators, who had always been passionate about Verghese’s works in private and felt a personal connection to him based on a shared hometown. The event series provided an opportunity for him to engage with an audience around themes that were personally meaningful to him both as a physician and a human, representing another way that the event series has been able to impact others beyond participation. The resident facilitator added, “I had a wonderful experience creating and facilitating the discussion showcasing Abraham Verghese’s writings. Discussing how one can feel ostracized within the medical community with … medical students, residents, attendings, and faculty was such a meaningful experience.”

The feedback received from participants and guest facilitators has indicated the success of the pilot event series among students and faculty at McGovern. Now in its third year, Narratives of Illness and Healing has continued with a new set of topics and facilitators. Even as McGovern Medical School and broader society transition out of the pandemic, the sessions continue to facilitate connections between McGovern students and faculty while helping participants maintain a sense of purpose amidst the challenges of practicing medicine. One faculty participant stated, “The series has such potential to create a community … at McGovern [whose members] could inspire one another and serve as role models of compassion and sensitivity, bringing the much-needed antidote to physician burnout and occupational distress.” For years to come, I hope the series will continue to unite students and faculty at McGovern in authentic dialogue about illness, healing, and what it means to be human.

The Narrative Medicine and Reflection Workshop Series: Addressing a Gap in the Medical Curriculum

Sarah Syed

What Students Feel: A Learner-Centered Approach to Narrative Medicine

The Narrative Medicine and Reflection Workshop Series (NMRWS), which I piloted in my fourth year of medical school, was developed during the 2021-22 school year alongside the Narratives of Illness and Healing event series, led by Megan Jiao. While both projects serve the similar purpose of building community and encouraging active reflection through narrative medicine, NMRWS was designed specifically for third- and fourth-year medical students to reflect on, share, and discuss personal and professional thoughts, ideas, and experiences longitudinally in a small-group setting over the clinical years.

At its inception, NMRWS was designed as part of my Medical Education Scholarly Concentration capstone project. For this project, I wanted to draw upon my humanities background as a Plan II Honors major at the University of Texas at Austin and my inclination toward literature and the arts more broadly. After I was directed toward Flores as a mentor, I learned that Megan Jiao and Anson Koshy had been working on McGovern’s Human Ties Digest arts magazine. It soon became clear that the four of us had a wealth of unique experiences and common interests that would give rise to novel narrative medicine initiatives at McGovern Medical School.

Through the workshop series, I hoped to explore questions I asked myself during my fourth year of medical school: How do we keep our skin thin in a career that can harden many? What have we seen in the clinical years of medical school that has supported, changed, or even dampened our original interest in medicine? And what are we learning in the clinical years that is not explicitly taught? I believed that students should be able to ask these questions in a safe space to consider not only the doctor-patient relationship and the patient experience but also the student experience. During my clinical years, I had not seen this addressed in a longitudinal, community-centered, and interactive way. As a result, the primary objective of the NMRWS was to fill this gap in the medical curriculum.

Objectives, Inspirations, and Dual Format

The workshop sessions themselves had three main objectives for students:

- Discuss texts (poems, visual art, songs, video, literature excerpts, and more) and apply them to personal and clinical experiences.

- Practice writing reflections surrounding themes and topics related to both the patient and medical student experience.

- Share reflections both within the small-group setting and beyond the workshop sessions.

To achieve these objectives, interested students were divided into two small groups. Each group consisted of ten to twelve students, and each was led by me and a faculty facilitator—Koshy for one small group and Flores for the other. Each group met one to two times per month for 90 minutes per session. The workshop sessions alternated between two formats throughout the year: the first type of session was called “read-reflect-respond,” and the second type was a dedicated writing workshop.

The format of the “read-reflect-respond” workshop sessions was modeled on virtual narrative medicine sessions conducted at Columbia University. Each session had a specific theme. For example, one session was titled “Keeping your skin thin: cynicism and burnout in medicine.” Other workshops related less directly to the medical field and allowed students to reflect more broadly on their lives while in medical school. One such workshop was themed “Beauty, friendship, and resilience in a new year.” For the “read” portion of the workshop, one or two texts were selected to be read aloud and discussed in a conversation led by me and the faculty facilitator. Texts included poems, visual art, songs, videos, literature excerpts, and more. The “reflect” portion of these sessions consisted of students responding to a writing prompt shown to them in the session. After writing for five to ten minutes, students were invited to share what they had written with their small group. Unlike the Columbia sessions, which were open to a new group of participants each time, I intentionally limited our sessions to the same groups of students. In this way, each session aimed to build upon the sense of comfort, trust, and community created in the last.

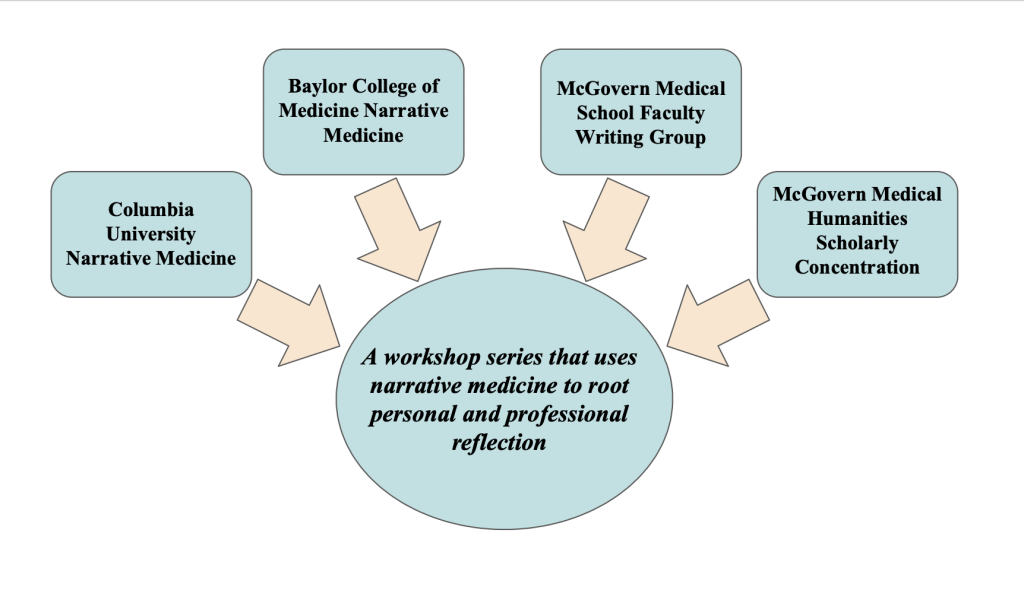

In the dedicated writing workshop format, we set aside a structured approach to narrative medicine to spend more time with our personal reflections. In these workshops, students were asked to bring in writing they had done on their own time to share with the group. The format for these sessions was influenced by three existing groups. The first was McGovern’s faculty writing group, which Flores and Koshy actively participated in. Through conversations with Flores and Koshy, I learned that sessions based entirely on participant writing had led to intimate and revealing dialogue. Second, according to my mentors, Baylor College of Medicine’s narrative medicine initiative served as an influence due to the interest that writing prompts garnered during those sessions. Third, McGovern’s Medical Humanities Scholarly Concentration served as an influence, as it required students to produce written reflections regularly to receive credit for the concentration. Of note, while reflections were read by the concentration director, there was no formal avenue for peers to share their reflections with one another. My writing workshops aimed to complement writing done for the scholarly concentration by offering an opportunity for peers to discuss the content of their reflective pieces and explore the feelings they inspired with others. In this setting, students could share curated pieces of writing that were more thoughtful than those that could be produced under the time constraints of the “read-reflect-respond” sessions. Ultimately, the writing workshop format was designed to further build community among students and offer feedback to students interested in publishing their work.

Importantly, by incorporating two different session formats into a workshop series, something unique that the Narrative Medicine and Reflection Workshop Series hoped to offer throughout the year was the opportunity to produce and revise written work for dissemination outside of any individual workshop session. Students were encouraged to submit to the Human Ties Digest, co-edited by Megan Jiao and Dr. Anson Koshy; humanities journals outside of McGovern; or the Houston-wide medical storytelling event Off Script. In this way, the workshop series aspired to build community among students in a small-group setting while extending the fruits of this reflection to the McGovern community, the Houston area, and beyond.

Evaluation and Future Directions

After each workshop, students were asked to fill out a post-workshop survey so that we could make adjustments to the series in real time. After the last workshop session of the year, students were asked to fill out a post-series survey. Of six third-year students and two fourth-year students, 100% of respondents agreed that the series helped them to better empathize, connect with, and treat patients; had a positive impact on their mental health; and addressed a gap in the medical curriculum for discussing what they experienced in the clinical years over time. Additionally, 88% of respondents agreed that they felt more connected to their medical school community and were likely to engage in reflective writing beyond medical school. One third-year student wrote of the sessions: “Through this workshop, I have not only been able to slow down and process my experience during this year of clinical rotations … I have also heard my colleagues do the same … In fact, being a part of our cohort’s workshop is one of the things I am proudest of during my clinical rotations.”

The survey also identified students who responded “neutral” to statements such as, “I feel confident using writing as a mode of reflection,” “I enjoy using writing as a mode of reflection,” and “I am likely to engage in reflective writing beyond medical school.” For me, these results opened doors to additional questions and potential conclusions. How can we help more students feel comfortable with writing and make the experience more enjoyable? In addition to discussion and writing, should other forms of active reflection be employed in these workshop sessions? Still, the survey indicated that all students took something away from the workshop series, whether or not writing was their reflective method of choice. This suggests that a workshop series that utilizes various modes of reflection—for example, both discussion and writing—may offer more to students than a workshop series that includes solely one or the other.

For the second iteration of NMRWS, four dedicated fourth-year students took over the workshops, each leading their own small group, and even more students took on facilitating positions in the third iteration. They will continue to collaborate with the Narratives of Illness and Healing event series and encourage students to share their work within and outside the McGovern community. With new student facilitators each year, the series can continue to grow and expand in different directions while promoting student wellbeing through the arts.

Creating Space for the Visual Arts within a Large Academic Healthcare Setting

Anson Koshy

A Digital Humanities Digest: Build It, and They Will Come

One of the advantages of working at the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics, with its well-established and popular scholarly concentration for medical students, is an endless stream of creative written and visual art. The scholarly concentration program was a well-oiled machine when I was recruited to join the center as part-time clinical faculty in 2016. Early on, part of my role at the center included reviewing journal entries by third-year medical students in their clinical clerkships and reviewing final projects submitted by Medical Humanities Scholarly Concentration students in their final year of medical school. However, in those early months of working at the center, I also found myself repeatedly explaining the center and its work to clinical faculty who had little contact with undergraduate medical education. When center faculty and staff met for a retreat to discuss future directions and initiatives shortly after I joined, we discussed creating a digital magazine showcasing the creative works submitted by students in the scholarly concentration. We hoped this would highlight their creativity and spread awareness about the center and our work in the humanities and ethics.

In the fall of 2018, the McGovern Center used a digital platform to launch the Human Ties Digest (Image 7). The initial edition of the digest was largely faculty-led, showcasing efforts and programs the center was involved in while highlighting creative works by humanities-focused medical students. We quickly recognized the value of collaborating with students and recruited two medical students to serve as co-editors of the digest, with a faculty member serving in a supervisory editorial role. For our medical school, we found that students were best positioned to serve as editors for the first half of their second year of medical school, with the goal of producing one edition of the digest at the midpoint of the year. Two first-year students were recruited in the spring of their first year and would subsequently serve as managing co-editors during their second year. After publishing one edition of the digest during their second year, co-editors were permitted to remain involved as part of an “editorial board” with varying levels of involvement in future editions based on interest.

Image 7: Partnering with Local Professional Artists: Reaching Beyond Academic Silos.

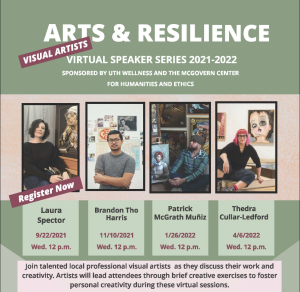

The McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics received a grant from Employee Wellness within our institution and launched an Arts and Resilience lecture series in 2017. Initially, the series showcased a wide array of local creatives, including poets, visual artists, dancers, vocalists, choirs, and prominent arts professionals from the Houston area, during a one-hour midday lecture or performance at the medical school. Sessions were open to anyone within the institution, with a variable amount of attendance depending on each topic. Like most things in life, things changed dramatically when the pandemic began, and I was tasked with taking over the series on a dramatically reduced budget. As a visual artist myself, I reached out to local professional artists I was familiar with and eventually recruited four diverse, Houston-based artists to provide a one-hour virtual talk about their work from their studios (Image 8). With this new series now housed in a virtual format, we chose to expand our audience by opening the series to the broader public. The series was well-received and created new opportunities to collaborate directly with local professional artists. Artists found benefit in having the opportunity to share their work with healthcare professionals, and they also advertised their sessions through their own networks, expanding the series’ reach and impact. One of our most recent lectures even included virtual participants from Europe and South America. Participating artists were provided an honorarium and a session recording, which they could later use as they saw fit.

Image 8: Equitable Collaboration with Artists: Practicing What We Preach.

Funding for visual arts-focused programming in a large healthcare institution setting can pose a significant roadblock to successful integration for many. Fortunately, clear correlations between the visual arts and practicing (and learning) medicine are well established in the literature. They can support successful proposals to prospective donors, often eager to support the intersection of the arts and medicine. Despite any anticipated budgetary challenges, it is critical to recognize the value of collaborating with local professional artists and compensating them for their time in a mutually agreed-upon manner early in the process. We have found that transparency is the easiest way to build a mutually beneficial collaboration with professional artists and clearly demonstrates how much we value the work they are bringing to the table. By outlining the expected number of attendees, proposed advertising plan, monetary compensation, timeline, and any additional variables early in the process, we can easily establish rapport with art-based professionals and create space for ongoing collaboration.

Future Directions

Now with five completed editions, the Human Ties Digest has fostered unique and unexpected benefits. Students involved with the editorial board of the digest have repeatedly shared how they are regularly asked about their work on the digest during residency interviews with great curiosity and interest. With the dissemination of each digest, awareness of this space as a potential publication source has increased further across the institution. We initially aimed to use the digest to showcase the work already being produced by learners involved in the McGovern Center; however, the 2021 edition (Image 9) consisted entirely of pieces submitted in response to a prompt related to “hope amidst uncertainty.” Administrators, staff, faculty, residents, and various employees from several departments submitted a range of paintings, poems, reflective writing pieces, and photography for consideration for publication, with little to no content pulled from those already involved in the center’s work. Particularly during and after the pandemic, those intimately involved in healthcare have sought ways to sustain their humanity and reflect on challenging encounters and experiences. It is increasingly apparent that the digest creates a space for all within our institution to foster, reflect, and share a small piece of themselves with others. These are the human ties that connect us to each other and ourselves and provide stability in these challenging times of distress. While there might be opportunities to expand the scope and reach of the Human Ties Digest, we remain focused, for now, on creating space to recognize the medical humanities as a necessary tool to establish lasting positive change for those committed to the service of others within a healthcare system that is broken and hampered by burnout.

Conclusion

The initiatives surveyed in this chapter continue to generate discussion for medical students and the broader McGovern community. Led by new facilitators, the two student-driven narrative medicine projects are in their third iterations, and the journey of writing and self-reflection through narrative medicine continues. Furthermore, the visual arts initiatives continue to engage additional student participants, faculty, and members of the arts-and-health community in Houston and beyond. Participating in these sessions has facilitated internal reflection among both students and faculty, conveying new views about oneself, the world, and patient care and, consequently, promoting personal and professional development. The McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics will continue to support these narrative medicine- and visual arts-based programs as vital opportunities to create, share, and reflect in the complex yet rewarding field of medicine.

References

Charon, R. 2001. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA 286(15): 1897-1902. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

Cooke, M., D.M. Irby, and B.C. O’Brien. 2010. Educating physicians: A call for reform of medical school and residency. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Howick, J., L. Zhao, B. McKaig, et al. 2022. Do medical schools teach medical humanities? Review of curricula in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 28(1): 86-92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13589