Expressive Therapies Pilot Group: Combining Art and Music Interventions to Enhance Patient Care in an Inpatient Psychiatric Hospital

Kula Moore and Chris Webb

https://doi.org/10.52713/BZDJ4214

Abstract

This paper outlines the inception and implementation of a pilot project at an inpatient psychiatric hospital. The authors received a grant to conduct a proposed expressive therapies group, combining art therapy and music therapy interventions to extend the reach of services to include more patients. With only two providers for art and music therapy hospital-wide, patients frequently experienced waitlists to receive these services. Providing a group space that merged music and art therapy offered timely service delivery and improved patient outcomes. Art and music therapy group interventions used in the pilot group are described, and findings demonstrated decreased post-group levels of patient-reported distress.

Keywords: art therapy, music therapy, group therapy, expressive therapy, mentalizing

Background

The Menninger Clinic has a rich history of expressive therapies. Art was offered to Menninger patients in Topeka, Kansas, as early as the 1930s. Mary Huntoon was an early pioneer and champion of art therapy with psychiatric patients, offering studio art as a means for healing and self-expression. She was followed by Don Jones and Robert Ault, who made meaningful contributions to the field of art therapy based on their work with Menninger patients (Wix 2000; Malchiodi 2007).

Similarly, music therapy has early roots at the Menninger Clinic. E. Thayer Gaston, a psychologist at the University of Kansas and sometimes called “the father of music therapy,” was instrumental in moving the profession forward by creating an organized educational system for music therapy. The first music therapy college training programs were created in the 1940s, and the first music therapy internship site was at the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas (American Music Therapy Association 2022; Johnson 1981).

Since that time, music therapy and art therapy have been incorporated into psychiatric rehabilitation services. Within the psychiatric rehabilitation model, clinicians from varied backgrounds use their areas of expertise to target treatment goals that ultimately improve functioning in living, working, and social environments. Psychiatric rehabilitation specialists facilitate many of the groups at the Menninger Clinic (Moore and Marder 2019). While Menninger patients already received individual and group art therapy and music therapy services, this pilot study offered them something new: a structured, cross-disciplinary, multimodal expressive therapies group.

Expressive Therapies Group Design

In 2018, we responded to a call for proposals, encouraging collaboration among faculty and staff to generate projects enhancing patient care, research, training, and operations. This pilot project sought to enhance patient care by increasing availability of expressive therapies services to adult patients, thereby addressing the problem of patient waitlists for individual art and music therapy. The focus of the proposed group was providing support for Individualized Treatment Plan (ITP) goals and offering opportunities for patients to enhance mentalizing capacity through the vehicles of art and music. The aims of this pilot project were to impact patients individually and interpersonally; support improved organizational outcomes; and benefit treatment teams by enhancing their understanding of patients through patients’ work in the expressive therapies group.

Mentalizing Approach

A mentalizing-based approach to the group was applied, based on the ethos of the clinic and training of the group facilitators. Mentalizing Based Treatment, developed by Anthony Bateman and Peter Fonagy, is an evidenced-based treatment for people with borderline personality disorder. It has since been applied to treat people with various psychiatric problems. Mentalizing involves attending to mental states in oneself and others, reflecting on thoughts, emotions, and intentions underpinning behavior. This natural process aids in making sense of what happens in one’s own mind and in the minds of others. However, in times of stress, people tend to find it challenging to mentalize (Bateman and Fonagy 2012; Allen et al. 2008). For many Menninger patients, failure to examine beliefs and clarify thoughts and feelings leads to interpersonal challenges and reinforces problematic assumptions about self and others. A mentalizing approach was natural for the creative arts therapists facilitating the group and aligned with the treatment patients received in other areas of programming.

Mentalizing provides a theoretical framework for creative arts therapies, and expressive therapies inherently support mentalizing aims. Visual art, music, movement, performance, and writing processes allow patients to share their minds, promote reflection on self and others, and activate inquisitiveness in those who witness the expression. When these acts of creating art or music take place in the presence of others who are attuned, responsive, and curious, it fosters connection, epistemic trust, and self-agency (Moore and Marder 2019; Springham and Huet 2018). Creative arts therapies offer immediate material to explore and facilitate the examination of thoughts and feelings on nonverbal sensorimotor, perceptual, and symbolic levels. Expressive arts therapies typically generate products that are tangible, preverbal, and encourage imagination; they invite patients to create and play with representations of material reality—physical art objects, that is, that represent self and are observed by self and others—by feeling emotions and creating an explicit mental perception of this reality (Havsteen-Franklin 2016; Verfaille 2016; Rubin 2011; Springham and Huet 2018; Springham and Camic 2017). Arts therapies promote affect consciousness, psychological mindedness, empathy, and mindfulness (Havsteen-Franklin 2016). Creative therapies also help treatment providers connect with and deepen understanding of patients’ experiences (Moore and Marder 2019).

The expressive therapies pilot group provided experiential, structured art and music therapy directives to promote patients’ exploration, reflection, and curiosity about thoughts and emotions. The group offered opportunities for patients to learn new coping skills and to connect with others through the combined use of art and music interventions.

Materials

The grant included funds to purchase art supplies, musical instruments, and other equipment for patient use in the expressive therapy group. Art supplies included varied 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional art media, including drawing materials, painting materials, collage supplies, clay, and paper. Music supplies included percussion instruments (detailed in weekly group descriptions), a smart tablet, and a wireless speaker.

Target Population

The group was open to all adult units, ages 18 and older. The typical length of stay at the hospital is four to eight weeks. Patients who were referred to the group had to meet safety criteria and demonstrate the ability to remain securely in the multipurpose room for the duration of the group, as group sessions took place in a building separate from patient units. Patients who were restricted to their units due to safety and impulsivity concerns or medical precautions were excluded from the group.

We shared information about the pilot group and referral process with staff in the hospital’s units. Next, we sent them a call for referrals, specifying the group’s aim and appropriate candidates. Patients were recommended for the group by their treatment team or by the expressive therapists. Group membership required a doctor’s order from the patient’s psychiatrist. Referred patients generally had some interest in creative practices or they experienced challenges with traditional therapy. Some level of willingness to try expressive therapy was expected, but no experience with art or music was required.

Format and Schedule

The group met once per week for 60 minutes over a six-week period. The group was limited to 16 patients, with space for about 4 patient referrals per unit. The group was open and voluntary; new patients could join at any time and existing patients could withdraw at any time. The group schedule was as follows:

- Facilitators introduce the group structure and guidelines to new patients (and review them with returning patients)

- Patients complete a self-reported pre-test measure

- Patients receive information on the weekly group topic

- Patients are invited to engage in the art and music interventions (Table 1)

- Facilitators guide group discussion to elicit processing and reflection

- Patients and facilitators cleanup the art and music materials and store artwork in folders

- Patients complete a self-reported post-test measure

Metrics

The Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) (Wolpe 1969) was administered at the beginning and end of each group. This measure is widely used in mental health settings and considered a useful tool to quantify the distress an individual feels at a specific moment. SUDS has sound psychometric properties and is used to assess the efficacy of various therapies. It is considered a reliable, valid, and sensitive evaluation tool, demonstrating correlation to clinical diagnoses and other measures of anxiety and depression (Kiyimba and O’Reilly 2020; Tanner 2012; Kim et al. 2008). In this pilot group, the SUDS was selected to focus on the patients’ internal experiences, especially their intensity of feelings of distress before and after the group. The SUDS also promoted patients to be mindful of their emotions in that they had to attune to their feelings to complete this assessment. This self-reported measure was a way of quantifying any distress the expressive therapies helped mitigate. In addition to completing the SUDS, patients were asked to take a survey at the end of the pilot to share about their experience of the group and provide us with direct feedback.

Weekly Group Interventions and Patient Examples

Week 1: Who Am I?

Patients were offered a selection of rhythm instruments, including paddle drums, djembes, a Kokiriko, cajon, bongos, triangle, rain stick, chimes, ocean drum, cowbell, maracas, and egg shakers. We chose to use rhythm instruments because they do not require the skill of melodic instruments. Patients were invited to select an instrument that represents some aspect of their identity. They were encouraged to take a few moments to explore the instrument’s sound and how they wanted to play it. Group members were asked to play their instruments in a way that represented their mood, personality, or anything important about themselves. As they played, they were invited to listen to themselves and to each other. The group played for approximately 15 minutes and verbally processed their experience afterward. Following the music intervention, the group was invited to sit at a table where a variety of art supplies (markers, watercolors, clay, pastels, charcoal, textured papers, brushes, and paint) were presented for use. The patients were asked to reflect on their musical experience through artmaking and, if they were willing, to share their art with the group while verbally processing the overall experience.

Week 1 Vignettes

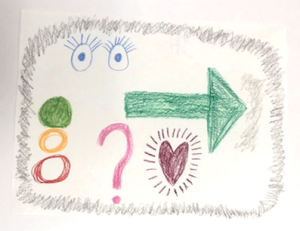

Dorothy, a young adult patient in treatment for chronic suicidality and borderline personality disorder, chose to play the Kokiriko. She noted that it looked easy to play and didn’t seem too loud. She also stated that she looked at the group facilitator (with whom she had existing therapeutic rapport) and copied what she did while playing. She explained that her art response (Image 1) represented various layers of depression, moving from a light blue sadness to a deep black pit of despair. Dorothy went on to tell us that her mental illness has been a large part of her identify for some time and makes it difficult to trust her own mind. Her engagement in the week 1 session yielded information about how she engaged in the world, as themes of self-doubt and subsequent dependence on others were present in other areas of treatment.

Image 1: Dorothy’s Week 1 Art Response

Sarah was an adult professional who struggled with anxiety, underpinned by emotional overcontrol and perfectionism. She chose to play the sitting drum, or cajon, and noted that she likes drums and used to play the saxophone. During discussion, Sarah shared that she could not help but notice the errors that she and others made while playing the instruments, and then she felt guilt about her critical thoughts. For her art response (Image 2), Sarah created repetitive lines in various colors using brush markers. She described her artwork as structured and grounding, reporting that she found the process of making her image to be soothing.

Image 2: Sarah’s Week 1 Art Response

Week 2: Meaningful Relationship

Patients were asked to think of a meaningful relationship in their life and select a song to share with the group that represents how the relationship felt. Due to time constraints, the music therapist used recorded music, searching for each song on the tablet and playing it from the wireless speaker as patients created art in response to the same prompt. Each person was given an opportunity to share their art and share their song selection, discussing who their meaningful relationship was with and what made it meaningful.

Week 2 Vignette

Donald used the prompt to reflect on his relationship with his young son. He chose the song “The Little White Duck” by Burl Ives to represent the relationship, noting that he and his son would listen to this song at bath time. Donald spoke of the anxiety he felt about being a good father. He used color pencils to represent the relationship (Image 3), creating symbols to depict his son’s wide-eyed curiosity, activeness, energy, and love. He represented himself as the gray border containing the symbols. Donald became tearful as he spoke about his son being a motivator for him to complete treatment.

Image 3: Donald’s Week 2 Art Response

Week 3: Open/Unstructured

The group took a pause from structured prompts. In the week 3 session, facilitators encouraged members to create art with the drawing, painting, and collage materials provided. For their leisure, patients were invited to select songs for background music that would play and inspire creativity as they worked. The group processed the artworks they created, their musical selections, and the overall experience.

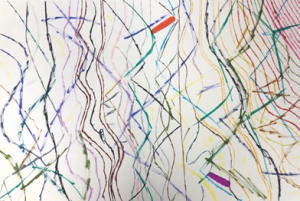

Week 3 Vignette

For the unstructured group, Sarah decided to practice what she was working on in treatment, which was challenging perfectionistic thinking. Unlike the structured drawing style from week 1, Sarah decided to make an abstract line drawing with no order or predictable pattern (Image 4). As she discussed her image, she shared with the group that many of her problems stem from perfectionism, and though she felt anxious while creating the drawing and looking at the final product, she wanted to push herself to tolerate the anxiety of imperfection. This marked difference from Sarah’s week 1 and week 2 art responses exemplified her progress in treatment.

Image 4: Sarah’s Week 3 Art Response

Week 4: Musical Conversation/Art Response

Patients were asked to choose a rhythm instrument to represent their “voice.” Once each person had chosen an instrument, they were paired with a peer and asked to have a nonverbal dialogue, using their instruments in place of their voices. The musical conversation was held between two individuals at a time, with the rest of the group observing their facial expressions and body language. Verbal processing occurred after the music conversations. Next, patients were invited to reflect visually on their experience with the art supplies provided, paying attention to emotions that were elicited from the music intervention. Last, the group processed the overall experience by sharing their art images and discussing their time in group.

Week 4 Vignette

Carl was a transgender patient, assigned female at birth and transitioning to male, who was in treatment to address depression. He chose the bass paddle drum to represent his voice. He explained that he chose the loudest, lowest instrument because that is what he would like his voice to sound like. It was notable that Carl perceived himself to play “aggressively” while group members commented that they experienced him to be playing quite softly. He noted that he is learning to find his voice and to take up more space in the world instead of hiding his authentic self.

Week 5: Iso-Principle

The Iso-principle is a music therapy technique used for mood management (Heiderscheit and Madson 2015). Patients were asked to identify an emotion they have difficulty managing or one they find challenging to move through. Next, each patient created a playlist that began with a song that matched their highest level of emotional intensity. Then, song by song, each patient completed their playlist by choosing music, lyrics, and/or rhythm that incrementally decreased the level of intensity, until they reached a baseline mood. The selected songs are intended to encourage or reflect an improvement in mood or physiological response and can readily be changed to move in the desired direction. Ideally, six or more songs are included in a playlist, and it is recommended to have no fewer than three songs. Each patient was asked to use art materials to depict what their emotional transition would look like based on their playlist. Group members volunteered to share their playlists, playing excerpts from each song as others listened and responded. We gave patients time to process the experience of creating their playlists and their art responses.

Week 5 Vignette

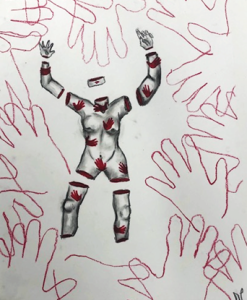

Collette was a young adult patient who struggled with an eating disorder, trauma, borderline personality disorder, depression, and anxiety. She also experienced dissociation while in distress. She created a playlist to help with grounding when she felt disconnected from herself and the world around her. Her art response began with a drawing that centered a severed body with no head or feet and small red handprints all over (Image 5). She told us that this represented the crux of her pain and the psychological response of splitting off from parts of herself. Collette also represented the emotional transition to baseline by tracing her own hands around the page, noting that this signified being more grounded and connected with her body.

Image 5: Collette’s Week 5 Art Response

Collette’s Iso-Principle playlist began by representing feelings of anxiety, anger, loneliness, and suicidality. As her songs continued, they invited a more neutral, euthymic feeling and acceptance of difficult emotions. Her playlist consisted of the following songs:

- Girl with One Eye – Florence + the Machine

- Blackbird – The Beatles

- Stay Alive – Andy Black

- Penny Lane – The Beatles

- Weightless – All Time Low

- This is Me – The Greatest Showman

Week 6: Hope

Patients were invited to engage in a discussion about hope—what it means to them and what it looks like in their treatment. The group discussion identified sources of hope and emotions the topic elicited. Patients were invited to use art supplies to represent what hope means to them and to participate in a musical improvisation. They chose instruments and played them in response to the question: what does hope sound like? Patients were given an opportunity to share their artwork and to discuss the music they made.

Week 6 Vignette

Kendra was an older adult patient with a history of trauma that began in childhood. She chose the wind chimes to represent what hope sounds like. She was observed closing her eyes while playing, and she explained that she did this to avoid distractions and to try to focus only on herself. She chose watercolor paints to create a rainbow (Image 6). During discussion, Kendra shared that she felt like she had been through constant rain and storms in her life, but hope meant that she could still look up to search for the rainbow.

Image 6: Kendra’s Week 6 Art Response

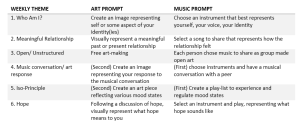

Table 1. Weekly Art and Music Interventions

Results

The pilot study had several results. First, more patients received art and music therapy during this six-week time period than would have been served in the absence of the study. The previous availability for 6 patients to receive services was almost doubled, with a total of 11 participants reached during the pilot group. Over this six-week period, no patients were waitlisted for either art or music therapy services. In addition to facilitating the group, the music therapist and art therapist also provided individual services when therapeutically indicated. Both qualitative and quantitative measures demonstrated the pilot study’s successes.

Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) Outcomes

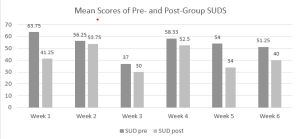

The findings from the SUDS indicate that the mean value of the group’s distress rating decreased each week (Figure 1). Collectively, patients reported a lower level of distress after every expressive therapy group intervention, with differences in pre- and post-test scores ranging from 2.5 to 22.5 points. Individually, patient scores varied; at times, data suggested a higher level of distress after the group than before. This variability was anticipated due to the difficult emotional content the group explored in the sessions.

Figure 1. SUDS Outcomes

Table 2. Weekly Pre- and Post-Test SUDs Scores

Expressive Therapy Questionnaire Outcomes

The primarily identified effect of the group is linked to emotional regulation goals, which all patients had included in their ITPs. The expressive therapies group seemed to encourage patients to identify, connect with, and relate to their emotions in new ways. Exact responses to the survey questions are as follows.

How did the expressive therapy group impact you or your treatment?

- “Took me out of my comfort zone”

- “It truly helped me to discover things about myself and attribute emotions that I didn’t know I was feeling”

- “It was helpful to focus on particular feelings to work through with art rather than using art to distract from my feelings”

- “This group gave me a positive outlet from difficult emotions”

What about the group did you find helpful?

- “The types of emotion we were prompted to express”

- “The ability to release emotions that I didn’t know how to release”

- “It was helpful to focus on particular feelings to work through with art rather than using art to distract from my feelings”

What aspect of the group were challenging?

- “Talking about the true meaning behind my art”

- “Finding the most suitable means of expression for my emotion”

- “Talking about an art piece tends to be more challenging for me than just making one”

- “Depicting emotions with art”

Is there anything you would like to change about the group? If so, what?

- “In the future I think it should be available to anyone (maybe not all at once but in small groups throughout treatment)”

- “More art feedback and personal music prompts”

- “Maybe just more time”

Did you share art or music from the group in other areas of treatment? If so, what was your intention? How was the artwork or music received?

- “Yes, I shared my art with IT [individual therapy]. I wanted to show her because I express myself better through art rather than words. It was exceedingly helpful for my IT sessions.”

- “No”

- “No”

- “No”

In the final section of the survey, participants were asked to rate their experience in the group on a 5-point Likert Scale. These were their mean values.

4.00 – found the music component of the group helpful

4.75 – found the art component of the group helpful

4.75 – were interested in continuing expressive therapy

4.75 – would recommend expressive therapy to others

Group members also shared feedback about the quality of art materials provided through the grant. They expressed excitement and appreciation for using high-quality materials and instruments.

Conclusion

We made several recommendations for the continuation of the expressive therapies group. First, increasing the length of the group from 60 minutes to 90 minutes would allow more time for patients to engage in the art and music tasks and more time for processing and discussion. Second, extending the group beyond 6 weeks could yield more robust data and further opportunities for patients to engage in expressive therapies.

We also encountered barriers with the timing and schedule of each of the 4 adult units. We may have been able to include more patients in the group had we taken more time to publicize the service and to prepare unit supervisors to adjust to the schedule change. Another unintended exclusion factor occurred as a result of scheduling: patients who were required to attend support groups at the same time as the expressive therapies group were not able to participate in the pilot study. Had our group occurred at a time that did not conflict with other specialty programming, more patients may have been able to join.

This grant-funded pilot project enabled the combination of art and music therapy interventions in an expressive therapies group for adults in inpatient psychiatric treatment. The present findings suggest an increased reach of services, decreased collective levels of patient-reported distress, and some facilitation of emotion regulation goals. Combining art and music therapy in a group format offered a unique experience for patients who participated in the group.

References

Allen, Jon G., Peter Fonagy, and Anthony W. Bateman. 2008. Mentalizing in clinical practice. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

American Music Therapy Association. 2022. Music Therapy Historical Review: Celebrating 60 years of music therapy history. https://www.musictherapy.org/about/music_therapy_historical_review/

Bateman, Anthony W. and Peter Fonagy (Eds). 2012. Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Havsteen-Franklin, Dominik. 2016. Mentalization-based art therapy. In Approaches to art therapy: Theory and technique, edited by Judith A. Rubin. New Yok, NY: Routledge.

Heiderscheit, Annie, and Amy Madson. (2015). Use of the iso principle as a central method in mood management: A music psychotherapy clinical case study. Music Therapy Perspectives 33(1): 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miu042

Johnson, Robert E. 1981. E. Thayer Gaston: Leader in scientific thought on music in therapy and education. Journal of Research in Music Education 29(4): 279–286.

Kim, Daeho, Hwallip Bae, and Yong Chon Park. 2008. Validity of the Subjective Units of Disturbance Scale in EMDR. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 2(1): 57-62. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1891/1933-3196.2.1.57

Kiyimba, Nikki, and Michelle O’Reilly. 2020. The clinical use of Subjective Units of Distress scales (SUDs) in child mental health assessments: a thematic evaluation. J Ment Health 29(4): 418-423.

Malchiodi, C. 2007. The art therapy sourcebook. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Moore, Kula, and Kate Marder. 2019. Mentalizing in group art therapy: Interventions for emerging adults. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Rubin, J. 2011. The art of art therapy: what every art therapist needs to know (2nd Ed). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Springham, Neil, and Paul M. Camic. 2017. Observing mentalizing art therapy groups for people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. International Journal of Art Therapy 22(3): 138–152.

Springham, Neil, and Val Huet. 2018. Art as relational encounter: An ostensive communication theory of art therapy. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 35(1): 4-10.

Tanner, Barry A. 2012. Validity of global physical and emotional SUDS. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 37(1): 31-4.

Verfaille, Marianne. 2016. Mentalizing in arts therapies. London: Karnac.

Wix, Linney. 2000. Looking for what’s lost: The artistic roots of art therapy: Mary Huntoon. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 17(3): 168–176.

Wolpe, Joseph. 1969. Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t05183-000