One Journey of Learning to Flourish: Integrating Contemplative Practices and the Arts for Wellness in Healthcare Institutions and Community Organizations

Alejandro Chaoul

https://doi.org/10.52713/CCBB3298

Abstract

In this personal essay, Alejandro Chaoul describes his discovery of Tibetan philosophy and contemplative practices while traveling in India as a young man, where he stayed for nine months. In the decades since, Chaoul has led numerous initiatives to integrate meditation and the arts for the benefit of patients, medical students, and physicians in Houston, Texas. This essay offers an overview of that work, with the intention to show one path within this vast exploration that may inspire or help others on similar journeys, as well as to open healthcare administrators and medical educators to the possibility of incorporating contemplative practices and arts in their programs.

Keywords: spirituality, mind-body medicine, contemplative practice, Tibetan yoga, breathing, sound, meditation, mindfulness, art

My Journey

Spirituality, art, and healing have fueled my search for meaning and purpose. I grew up in the 1970s and ’80s in Argentina with terrorism and military repression. Art, reading, imagination, and learning to meditate became my unwavering supports during what I called “existential attacks.” These experiences guided me to keep searching for meaning. Years later, Houston became my safe haven and foundation for flourishing. Its universities, medical center, art, and spiritual spaces all became inspirations that manifested in healing practices for people with cancer and caregivers, healthcare providers, medical students, and professors, as well as for myself. In this multimedia essay, I will share some examples of art and healing through contemplative practices—especially meditation and Tibetan yoga—that I have been refining over several decades.

I was probably eight or nine years old when a bomb exploded in a supermarket a few blocks from where we lived in Buenos Aires. I also remember not feeling safe opening the street door of my apartment building if police or military personnel were nearby. I felt scared of terrorists and of the military government.[1]

During the same years, I would often wake in the middle of the night, sweating, gripped by the thought, “I will die, and then what?” I called these experiences “existential attacks.” Writing this essay has given me the opportunity to connect, for the first time, my existential attacks to my country’s struggle and the environment I lived in. What has been clear to me all along, though, is that those dreadful feelings fed and supported my continuous inner search for meaning.

Art and movies were my escape, and then Herman Hesse’s book Siddhartha (1922) became my guide. It relays the story of a man who notices, even in his palatial life, that there is suffering. Notably, he identifies the sufferings of birth, old age, sickness, and death. This observation spoke to me loudly, though its clarity emerged over time. After eight readings, I finally understood that life involves suffering from birth to death, and that meditation practices are tools to gaining understanding and awareness—to waking up! Siddhartha is the story of Buddha Shakyamuni’s life, and “Buddha” means “the awakened one.” His first teaching, the Four Noble Truths, is about understanding suffering and gaining liberation from it by waking from the stupor and ignorance in which emotions like anger and attachment keep us bound. The path of liberation is traversed by meditation, and I became eager to learn.

My fortune, or maybe my karma, had it that my best friend’s uncle was a meditation teacher, and through him I learned transcendental meditation (TM) and received my secret mantra. I practiced daily and learned that this form of meditation comes from India, where the Beatles traveled to learn from the famous TM teacher Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. I loved not just the Beatles’ music but also the art of their album covers! I wondered if meditation had inspired some of that dream-like art.

The situation in Argentina continued to be uncertain and violent, and I had an opportunity to study abroad. As an international student at Boston University (BU), my favorite place was the plaza of the Marsh Chapel, with its “Freedom at Last” sculpture of 50 doves flying in formation representing the aspiration of freedom in all 50 states. The sculpture was made in honor of Martin Luther King Jr., who received his PhD in theology from BU. My world broadened on the BU campus. I attended lectures by Howard Zinn and Elie Wiesel, among others. I also learned about Indian philosophy and religion, vegetarian cooking, and Zen meditation.

A couple of years after graduation, I decided to backpack through India, partly because I had made many Indian friends at BU, but mainly to find a spiritual teacher. On that fabulous journey, the first spiritual guide I met was U.G. Krishnamurti, whose teachings crumbled my philosophical understanding. I became more at home in my body and my heart, freed from living too much in my head and in fight-or-flight mode. Swami Chinmayananda became another wonderful teacher for me, helping me understand life as maya, illusory, allowing me to get less mired in life’s fleeting dramas. Finally, after visiting many Tibetan monasteries in the Northern Indian region of Ladakh, I traveled to meet His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala. Standing in line in a public blessing, I got to be face-to-face with him for the first time. I offered him the traditional white khata scarf as a sign of deep respect, and, when he handed it back to me with some Tibetan medicine, I was speechless. I stayed reflecting under a tree with tears flowing down my face, feeling a connection so deep it is difficult to describe in words. A moment that marked my life forever. Someone on that trip had told me that spiritual exploration is like digging in different holes and advised me to keep digging whenever I reach water. Meeting His Holiness the Dalai Lama certainly felt like finding water. I had met not only my Teacher but also my tradition. That was in early 1990. Ever since, with help from other Tibetan teachers, I have continued digging and learning. His Holiness the Dalai Lama used the phrase, “A good heart is the best religion.” Simple and yet profound, that saying resonated with me deeply. It had an important mark on how I continue to learn and teach spirituality.

The nine months I spent on that first trip to India seemed like a second gestation period. Afterward, I felt I could bring some healing to my country and my family. So in 1992 I helped organize a visit by His Holiness the Dalai Lama to Argentina, and I did so again in 1999. Later, he journeyed there two more times. During that first visit, I helped publish a book of many of His Holiness’s teachings translated into Spanish. Of course, I titled it Un Buen Corazón es la Mejor Religión (A Good Heart Is the Best Religion).

To strengthen my intellectual grasp of Tibetan contemplative techniques, I earned a master’s degree in Tibetan religions. In that program, I also learned about the significance of certain types of Asian art that invite engagement and practice. These included symbols, deities, and mandalas, the latter of which are both art forms and spiritual supports for one’s practice. I was drawn particularly to the Tibetan mandalas. The concept of a mandala (khyil khor in Tibetan, meaning center and periphery) helped me understand how we are all interrelated wherever we are in the mandala, and how, by connecting to our own center, we can also connect more deeply to others. Indeed, in Tibetan, there is a metaphorical way of asking a person how they are doing. You say, “How clear is your mandala?”

My original trip to India served as a nine-months gestation that birthed a lifelong relationship with the contemplative healing tradition. Over the years, I traveled repeatedly to monasteries in Nepal and India, where I absorbed instruction from an older generation of Tibetan teachers. Building on my earlier understanding of mandala, I began to perceive my body as a microcosm of the larger mandala of the universe. In these far-flung places, I also learned about local art, culture, community, and rituals. For example, I gleaned that certain paintings, statues, and other objects form an integral part of the teaching by explaining and supporting Tibetan yoga theory, philosophy, and practice.

Eventually, back in Houston, my own meditation practice would allow me to interweave various organizations, artists, and healers into a vibrant contemplative community. That work was first motivated by illness—when both my father and one of my Tibetan teachers were diagnosed with different types of cancer, the same disease from which my grandmother and another teacher had already passed. Their experiences led me to wonder about the possible benefits that Tibetan yogic practices—especially simple breathing and movement techniques—could have for people with cancer and for their caregivers.

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

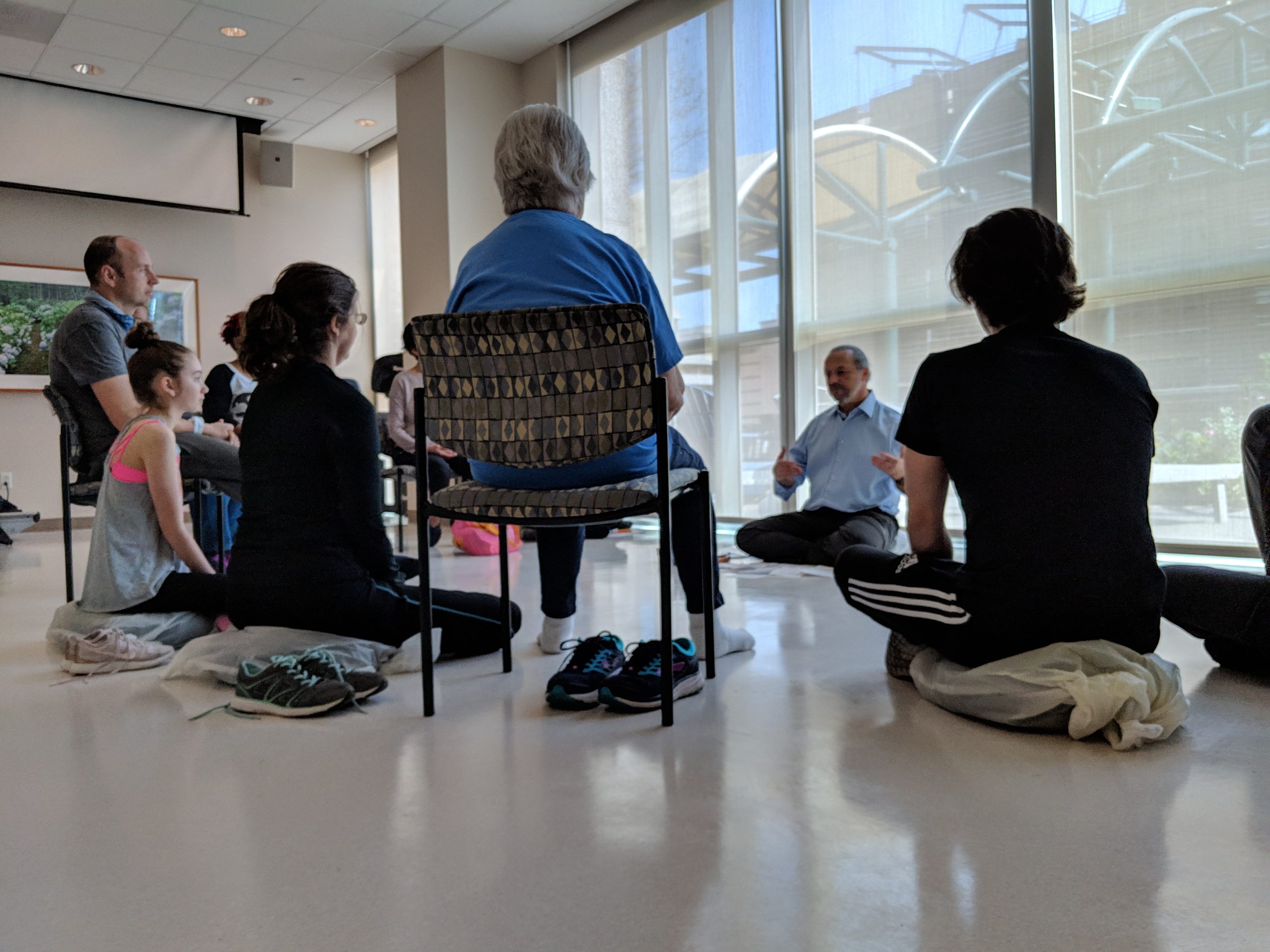

In 1999, I had an opportunity to start volunteering at MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Place of Wellness, leading meditation for anyone touched by cancer as part of addressing the psychosocial aspects of their illness experience. Following the advice of my teachers, I taught basic meditation techniques that included mindfulness, breathing, and simple Tibetan yoga movements. These classes were well-received. As I continued my work at MD Anderson, I was hired as a Mind-Body Intervention Specialist to create research protocols, designing meditation and yogic classes and trainings as interventions for people touched by cancer and their caregivers.

The research studies were conducted at MD Anderson’s Integrative Medicine Program. Following George Engel’s seminal paper in Science, the aim was to provide healing focused not just on the physical (i.e., biomedical) but also on the psychosocial-spiritual aspects of persons (Engel 1977). In other words, although the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of health and illness that Engel had proposed over two decades earlier was not pervasive in US healthcare, that model was part of the philosophical foundation of our Integrative Medicine Program.

Complementing Engel’s model was another part of that foundation: Arthur Kleinman’s Illness Narratives, which describes differences between disease—in this case, cancer—and the whole illness experience that a patient endures (Kleinman, 1988). Kleinman characterizes illness as an innately human experience that affects not only the patient but also their family and loved ones. Kleinman also emphasized the value of understanding the patient’s experiences as a story or narrative. Thus, to probe different aspects of a patient’s story, our interdisciplinary team of integrative medicine/health providers consisted of physicians, nurses, physician assistants, biomedical researchers, psychologists, acupuncturists, massage therapists, music therapists, and mind-body practitioners. When we convened every Thursday morning, we took our cues from Engel and Kleinman and discussed not only the patient’s medical chart but also their story, interests, and roles that loved ones were playing in their lives. That discussion, with attention and input from all members of the team, richly informed the patient’s treatment plan.

Fortunately, for my dissertation, I had the chance to join my interests in the humanities and the sciences. In addition to translating Tibetan yoga texts and researching their history and current ways of practicing them today in the monasteries, I was able to include a clinical research study. With Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche as my advisor and Dr. Lenzo Cohen as principal investigator, I helped lead a pilot study of Tibetan yoga for people with lymphoma. Thirty-nine patients were randomly assigned to either an intervention or a control group. The intervention group received a seven-week Tibetan yoga program, while members of the control group did not. Patients in both groups completed self-reported evaluations at baseline (i.e., before the program began), as well as one week, one month, and three months after the seven-week program. The study took almost a year to complete. We began the seven-week Tibetan yoga sessions after each recruitment cycle, with four to nine patients in each session.

89% of Tibetan yoga participants completed at least two yoga sessions; 58% completed at least five sessions. Overall, the results indicated that the Tibetan yoga program was feasible and well-liked. The majority of participants indicated that the program was “a little” or “definitely” beneficial, with no one indicating “not beneficial.” After the study, a majority also maintained a regular yoga practice, with some practicing twice a week or more. Patients in the Tibetan yoga group reported significantly lower sleep disturbance scores during the follow-up period than did the patients in the control group. This included better subjective sleep quality, faster sleep latency (i.e., the moment one decides to sleep until one actually falls asleep), longer sleep duration, and less use of sleep medications. Improving sleep quality in a cancer population may be particularly salient, as sleep is crucial for recovery. Fatigue and sleep disturbances are common problems for patients with cancer. In these ways, our research focused on behavioral changes and quality-of-life improvement, which aligned with Engel and Kleinman’s emphases. It is also worth noting that none of the patients involved had any previous knowledge of Tibetan yoga, and the majority had no prior experience with a meditative or yoga practice. Reported in Cancer, our study was the first randomized controlled trial of any yoga intervention in a cancer population and the first clinical study of a Tibetan yoga intervention with any population (Cohen et al. 2004).

I became more engaged in research and continued teaching groups and individual classes supporting people touched by cancer. Often, patients’ loved ones came with them to the classes, and I encouraged them to practice together. In 2006, I was part of a team that received a large grant from the National Cancer Institute to do a loftier study of Tibetan yoga for women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy that included an active control group in addition to standard of care. One of the publications from that study, also in Cancer, detailed how those who practiced more than twice a week had long-term benefits. This was useful information for clinicians in integrative medicine to be able to recommend these practices with an appropriate “dose” (Chaoul et al. 2018). And a few years earlier, we reported in Psychooncology on a Tibetan yoga intervention for adult lung cancer patients and their caregivers (Milbury et al. 2015). During those years, we also created audio and videos of Tibetan yoga practices that included meditation, breathing, sound, and movements. Originally designed for people who were inpatients, these videos were later made available online to encourage wider use.

As mind-body practices like mindfulness and yoga became more popular and gained evidentiary support, we created a new group of classes called meditation and daily life. The idea behind these classes was to help people bring more mindfulness to their entire day—what is sometimes called informal meditation. To integrate meditation into daily activities, we offered four sessions, which rotated weekly: meditation and tea, meditation and nature, meditation and writing, and meditation and art. In the latter, patients would express themselves through coloring a mandala while I guided them through a meditation.

We also created a research meditation app in English and Spanish designed to reduce patients’ psychological distress and anxiety. The app was equipped with on-demand meditations and downloaded to an iPod Touch given to outpatient cancer patients. The results were published in Integrative Cancer Therapies (Lopez et al. 2023). This pilot study demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of a meditation app for cancer outpatients. Those who used the meditation app reported improvement in several measures of symptom distress.

As MD Anderson faculty and staff became increasingly interested in mind-body practices, I began teaching through Faculty Health and Employee Health. Later, I extended similar offerings to UTHealth Houston’s medical school, dental school, and employee health program.

Word of our research and programs continued to spread. When colleagues from the University of Texas Cizik School of Nursing expressed interest in meditation research, we conducted a clinical study for people who had a stroke, and another one on people with knee osteoarthritis pain. The latter study was especially interesting, as it combined two interventions: meditation and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). This creative pairing of interventions supported participants’ desire for convenience; both the meditation and the tDCS could be done at home. Because initial findings suggested the promising clinical efficacy of this combination of modalities (Ahn et al. 2019), we are now concluding a larger NIH-funded study based at the University of Arizona. We hope our study will inspire other evidence-based couplings of meditation with medical technologies.

The Rothko Chapel: Meditation, Healing, and Art

Immediately after the attacks on September 11, 2001, I joined numerous people from various faith traditions beside Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk sculpture outside the Rothko Chapel in Houston. Though we didn’t know exactly what, we were determined to do something that would promote peace and healing. There beside the reflecting pool, we gathered to discuss possibilities openly and in a safe space.

The Rothko Chapel’s triad of art, spirituality, and advocacy for human rights inspired me to combine art and contemplative practices through a yearlong program called “12 Moments of Meditation” held at both the Rothko Chapel and the Texas Medical Center. This program was made possible through the support of the director of the Rothko Chapel, K.C. Eynatten; the president of the Institute of Spirituality and Health, Dr. Jim Duffy; and members of MD Anderson, Interfaith Ministries of Greater Houston, and the Jung Center. Each month, we invited a presenter from a different faith tradition to share their perspective on faith and to lead and engage all attendees in a practice. Each guest speaker presented twice, once in the Rothko Chapel and again in the Texas Medical Center (e.g., in a hospital chapel), where the presenter would focus more on healing. A few years into the program, we changed the title to “12 Moments of Spirituality and Healing.” Sessions at the Rothko Chapel were attended by the general public, while those in the medical center attracted mostly staff, patients, and caregivers. These sessions were so popular and impactful that they endured far beyond the original one-year vision, not ceasing until the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted such gatherings in 2020.

My passion for the arts also led me to link meditation and art in other spaces, such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, during its retrospective on Mark Rothko. There, I facilitated four meditation sessions, one in each of the four galleries, focusing on how the specific Rothko works displayed could support participants’ meditative experiences. Similarly, at Rice University, I led meditations in the Moody Center for the Arts as well as outdoors on campus.

Although I did not seek to record the impacts of these experiences on participants in a systematic way, I was consistently encouraged by the positive feedback I received from many. Their enthusiasm for the meditation sessions—especially those coupled with visual art—inspired me to plan and lead them again and again.

The Jung Center’s Mind Body Spirit Institute

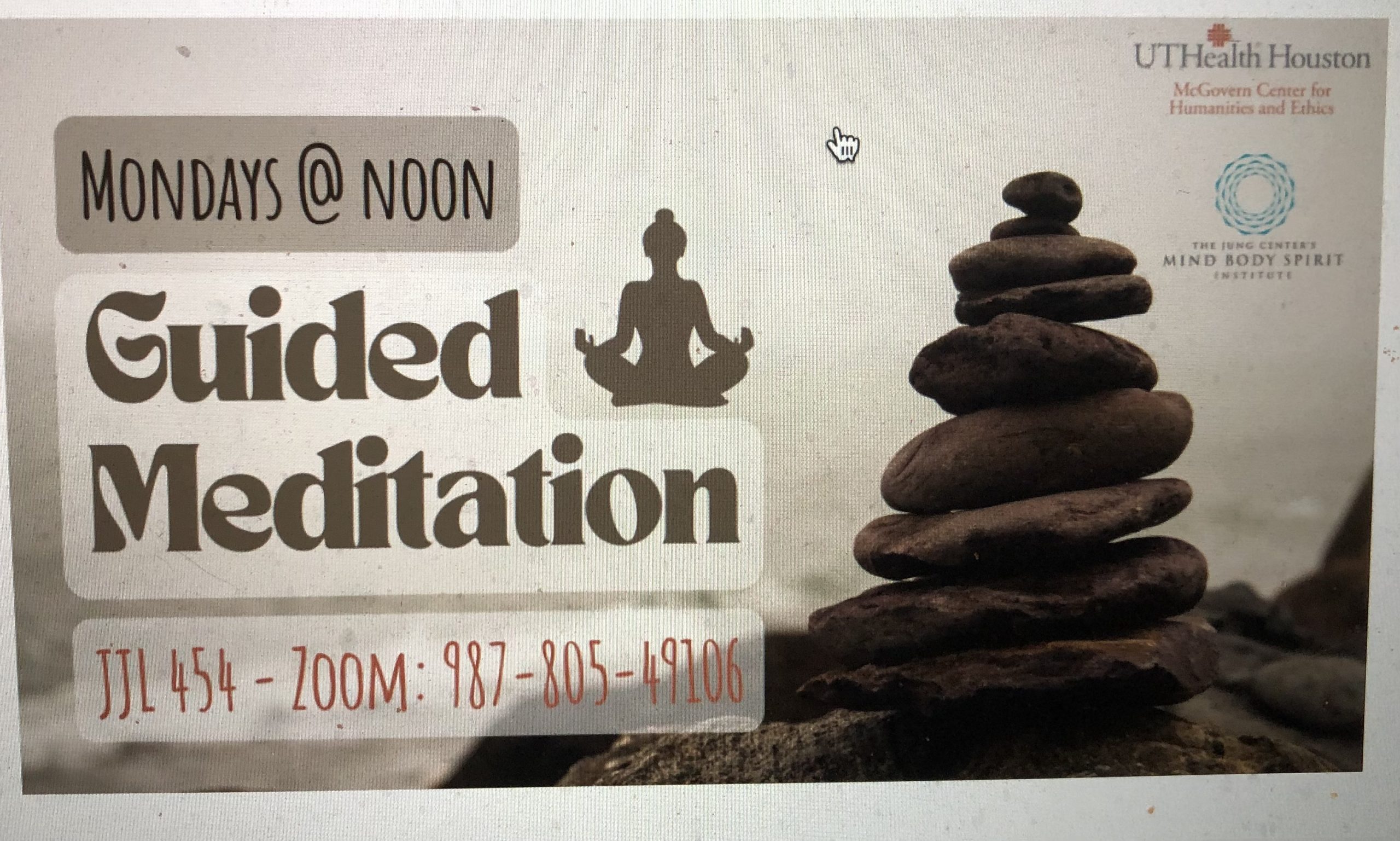

After twenty years at MD Anderson and in other Texas Medical Center institutions, I wanted to do more for the larger Houston community. When I began searching for ways to anchor and amplify the flourishing of meditative, connective, and healing experiences into others’ lives, I thought immediately of the Jung Center of Houston. For over six decades, the Jung Center has served as a nonprofit forum for dynamic conversations on a diverse range of psychological, artistic, and spiritual topics. Years earlier, in 1999, I had begun teaching courses and leading workshops there. Now I wanted to strengthen my bond to the place. Through many conversations over coffee with Sean Fitzpatrick, executive director of the Jung Center, we developed a plan for the Mind Body Spirit Institute (MBSI). Our vision was to offer programs that would teach individuals to live healthier and more balanced, productive, and meaningful lives. MBSI was launched in 2017, and, with initial support from the Huffington Foundation and others in Houston, I became the founding director, moving almost full-time into the Jung Center.

From the outset, MBSI’s goal was to bring more contemplative practices to four sectors of our community: healthcare, education, nonprofit organizations, and corporations. We began partnering with companies and institutions that recognized the value of empowering their team members to be more connected to each other and to themselves. As a result, we created professional training programs (PTP). Our PTPs trained healthcare workers and social workers from organizations working with underserved communities. One of the unique characteristics of this training was its combination of spirituality, Jungian psychology, and mind-body-spirit techniques. Our trainees found the tools we taught to be useful in both their professional and personal lives, supporting their resilience as caregivers. These PTPs were taught by three faculty with different spiritual perspectives and ethnic backgrounds, which enriched the content and methodology.

Another example of the impact of our PTPs was our work with the Houston Area Women’s Center (HAWC), a multiracial, multilingual agency that supports survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, and sex trafficking. Through the financial generosity of the Rockwell Foundation, we were able to train almost thirty HAWC staff members. This nine-month PTP included many small group and individual sessions, some of which were conducted in Spanish. In the end, HAWC employees reported that they felt newly empowered by the techniques we taught. Several staff members told us they often applied lessons from the training during their meetings with clients.

Through additional funding from the Huffington Foundation, our PTP work continued with Bread of Life, an organization that seeks to relieve hunger and address homelessness. One of their directors wrote, “The experience ushered in the awareness that if the good work is to continue, we must commit to not neglecting our own needs and consider how our organizational processes and policies can assist in paving the way toward wellness for all.” Another PTP, supported by H-E-B, engaged nurses with the Alief Independent School District.

Since MBSI began seven years ago, our work has grown exponentially. We have gone on to train healthcare professionals at MD Anderson and Houston Methodist Hospital and to work with small non-profits in what we called compassionate professional renewal (CPR). Some of the CPR sessions combined mind-body practices and art. For example, a training for the Houston Coalition Against Hate was held in a Zen exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. There, we conducted a meditation session that drew participants’ attention to the simplicity of the Zen art as a meditative expression. Participants reported informally that the session helped reduce their stress and increase their sense of presence in their immediate environments.

Conclusion

A quarter century ago, when I began working in the Texas Medical Center, the message I heard repeatedly from numerous people and institutions was that the arts and contemplative practices do not belong in healthcare. What changed? As I have sought to convey in this essay, what has emerged is a wealth of evidence for the health benefits of integrating the arts with yoga, meditation, and other contemplative practices. Inspired by a diversity of model teachers—from Arthur Kleinman to George Engel and His Holiness the Dalai Lama—I have been fortunate to play a small role in the growing acceptance of ideas and exercises that were once viewed, at best, as “alternative.”

Long ago, large swaths of what is now Houston were swampland. Whenever I remember that history, what comes to mind is the lotus, which can’t flourish without the mud from which it grows. By analogy, I think of our arts-and-health work in Houston as a collective effort to transform our local healthcare landscape, bringing forth flourishing lives in this former swamp. For me, the following photo represents the goal of transformation—individual and collective—and inspires me to continue my journey of learning to flourish.

References

Ahn, Hyochol, Chengxue Zhong, Hongyu Miao, Alejandro Chaoul, Lindsey Park, I. Hua Yen, Manuel A. Vila, Setor Sorkpor, and Salahadin Abdi. 2019. Efficacy of combining home-based transcranial direct current stimulation with mindfulness-based meditation for pain in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 70: 140-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2019.08.047

Chaoul, A., K. Milbury A. Spelman, K. Basen-Engquist, M.H. Hall, Q. Wei, Y.T. Shih, B. Arun, V. Valero, G.H. Perkins, G.V. Babiera, T. Wangyal, R. Engle, C.A. Harrison, Y. Li, and L. Cohen. 2018. Randomized trial of Tibetan yoga in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer 124(1): 36-45. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30938

Cohen, Lorenzo, Carla Warneke, Rachel T. Fouladi, M. Alma Rodriguez, and Alejandro Chaoul-Reich. 2004. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer 100(10): 2253-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20236

Engel, George L. 1977. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 196(4286): 129-36. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Hesse, Hermann. 1973. Siddhartha. Gyldendal. (Original work published 1922.)

Kleinman, Arthur. 1988. The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York: Basic Books.

Lopez, Gabriel, Alejandro Chaoul, Carla L. Warneke, Aimee J. Christie, Catherine Powers-James, Wenli Liu, Santhosshi Narayanan, et al. Self-administered meditation application intervention for cancer patients with psychosocial distress: A pilot study. 2023. Integrative Cancer Therapies 22: 153473542211487. https://doi.org/10.1177/15347354221148710

Milbury, K., Chaoul, A., Engle, R., Liao, Z., Yang, C., Carmack, C., Shannon, V., Spelman, A., Wangyal, T., and Cohen, L. 2015. Couple-based Tibetan yoga program for lung cancer patients and their caregivers. Psychooncology 24(1): 117-20.

- The feature film Argentina, 1985 and the Academy Award-winning La Historia Oficial offer glimpses of that era in Argentina. ↵