1.3 Netflix: Tech and Timing

Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the basics of the Netflix business model.

- Appreciate why other firms found Netflix’s market attractive, and why many analysts incorrectly suspected Netflix was doomed.

- Understand the long tail concept, and how it relates to Netflix’s ability to offer the customer a huge (the industry’s largest) selection of movies.

- Understand the role that market entry timing has played in Netflix’s success.

- Understand the role Amazon Web Services play in Netflix’s business.

Netflix is an American media-services provider headquartered in Los Gatos, California, founded in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph in Scotts Valley, California. Netflix allows subscribers to stream movies and TV shows on their devices for a flat subscription fee. The company started as an over the mail DVD rental company in 1997, its streaming service in 2007 and has since become one of the highest valued media service providers.

Studying Netflix gives us a chance to examine how technology helps firms craft and reinforce competitive advantage. We’ll look at the components of the firm’s strategy and learn how technology played a starring role in placing the firm atop its industry. We also realize that while Netflix emerged the victorious underdog at the end of the first show, there will be at least one sequel, with the final scene yet to be determined. We’ll finish the case with a look at the very significant challenges the firm faces as new technology continues to shift the competitive landscape.

Highlights from Netflix’s History

Reed Hastings, a former Peace Corps volunteer with a master’s in computer science, got the idea for Netflix when he was late in returning the movie Apollo 13 to his local Blockbuster store. The forty-dollar late fee was enough to have bought the video outright with money left over. Hastings felt ripped off, and out of this initial outrage, Netflix was born – or at least this was the myth created by the founders to fuel sentiment against the then market leader that charged those huge late fees (Washington Post, 2014).

The model the firm originally settled on was a DVD-by-mail service that charged a flat-rate monthly subscription rather than a per-disc rental fee. Customers did not pay for mailing expenses, and there were no late fees. Videos arrived in red Mylar envelopes. After tearing off the cover to remove the DVD, customers revealed prepaid postage and a return address. When done watching videos, consumers just slipped the DVD back into the envelope, resealed it with a peel-back sticky-strip, and dropped the disc in the mail. Users made their video choices in their “request queue” at Netflix.com.

In 2007, Netflix started its streaming service and offered a variety of subscription options. While 2.7 million DVD-by-mail subscribers still remain (CNN, 2019), by early 2019 “Netflix has over 148 million paying streaming subscribers worldwide as well as over 6.56 million free trial customers. Of these subscribers, 60.23 million were from the United States (Statista, 2019)”.

In 2013, Netflix debuted original content like House of Cards and Orange is the New Black (THR, 2013), both series went on to win multiple traditional television awards. While Netflix continues to stream TV shows and movies from a variety of content providers, as of late 2018/19, they invest around $8 billion in original content with “1,000 originals total on the service by the end of 2018. […] More than 90% of Netflix’s customers regularly watch original programming.” (Variety, 2018)

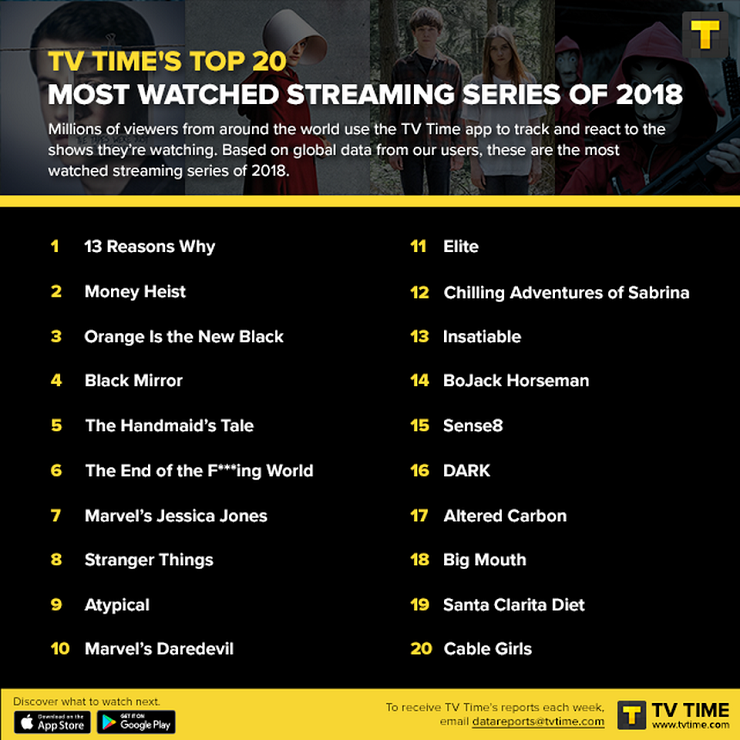

The Top 20 TV Shows Streamed In 2018: Only One Isn’t On Netflix (#5 airs on Hulu, THR, 2019).

It may be hard to imagine from today’s perspective, but Netflix wasn’t always considered a success. Businesses are supposed to want to go public. When a firm sells stock for the first time, the company gains a ton of cash to fuel expansion and its founders get rich. Going public is the dream in the back of the mind of every tech entrepreneur. But in 2007, Netflix founder and CEO Reed Hastings told Fortune that if he could change one strategic decision, it would have been to delay the firm’s initial public stock offering (IPO): “If we had stayed private for another two to four years, not as many people would have understood how big a business this could be” (Boyle, 2007). Once Netflix was a public company, financial disclosure rules forced the firm to reveal that it was on a money-minting growth tear. Once the secret was out, rivals showed up.

Hollywood’s best couldn’t have scripted a more menacing group of rivals for Hastings to face. First in line with its own DVD-by-mail offering was Blockbuster, a name synonymous with video rental. In 2007, 40 million U.S. families were already card-carrying Blockbuster customers, and the firm’s efforts promised to link DVD-by-mail with the nation’s largest network of video stores. Following close behind was Wal-Mart—not just a big Fortune 500 company but the largest firm in the United States ranked by sales at the time. In Netflix, Hastings had built a great firm, but at the time, an Internet “pure play” company without a storefront and with an overall customer base that seemed microscopic compared to Blockbuster and Wal-Mart. Yet, Wal-Mart eventually had cut and run, dumping their experiment in DVD-by-mail. Ultimately, Blockbuster had been mortally wounded, hemorrhaging billions of dollars in a string of quarterly losses. And Netflix? Not only had the firm held customers, but it also grew bigger, recording record profits.

Selection: The Long Tail in Action

During the DVD rental era, customers have flocked to Netflix in part because of the firm’s staggering selection. A traditional video store (and in the late ’90s and early 2000s Blockbuster had some 7,800 of them) stocked roughly three thousand DVD titles on its shelves. For comparison, Netflix was able to offer its customers a selection of over one hundred thousand DVD titles. At traditional brick-and-mortar retailers, shelf space is the biggest constraint limiting a firm’s ability to offer customers what they want when they want it. Which films, documentaries, concerts, cartoons, TV shows, and other things that made it inside of a Blockbuster store, what they carried was dictated by what the average consumer was most likely to be interested in.

For any store, finding the right product mix and store size can be tricky. Offer too many titles in a bigger storefront and there may not be enough paying customers to justify stocking less popular titles (remember, it’s not just the cost of a product, as firms also pay for the real estate of a larger store, the workers, the energy to power the facility, etc.). There’s a breakeven point that is arrived at by considering the geographic constraint of the number of customers that can reach a location, factored in with store size, store inventory, the payback from that inventory, and the cost to own and operate the store. Anyone who has visited a physical store understands that shelves and show floors can only hold so many products.

Many pure-play (online only) businesses are able to run around these limits of geography and shelf space. Internet firms that ship products can get away with having highly automated warehouses, each stocking just about all the products in a particular category. And for firms that distribute products digitally (iTunes, Hulu, Office Online), the efficiencies are even greater because there’s no warehouse or physical product at all.

Offer a nearly limitless selection and something interesting happens: there’s actually more money to be made selling the obscure stuff than the hits. In the early 2000s at Netflix, roughly 75 percent of DVD titles shipped were from back-catalog titles, not new releases. At Blockbuster outlets the equation is nearly flipped, with some 70 percent of their business coming from (then) new releases (McCarthy, 2009). In 2019, Netflix streams obscure things and massive hits. Blockbuster is gone and In 2019, Netflix accounts for 15% of the world’s, 19% of the US’ internet traffic.

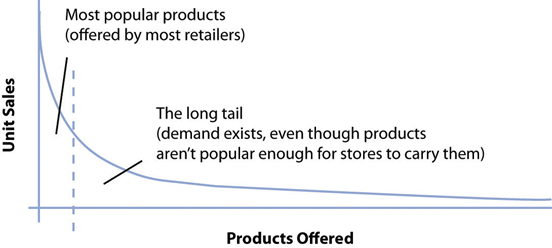

The phenomenon whereby firms can make money by selling a near-limitless selection of less-popular products is known as the long tail. The term was coined by Chris Anderson, an editor at Wired magazine, who also wrote a best-selling business book by the same name. The “tail” (see the figure below) refers to the demand for less popular items that aren’t offered by traditional brick-and-mortar shops.

Anderson, C., “The Long Tail,” Wired 12, no. 10 (October 2004).

While most stores make money from the area under the curve from the vertical axis to the dotted line, long tail firms can also sell the less popular stuff. Each item under the right part of the curve may experience less demand than the most popular products, but someone somewhere likely wants it. The total demand for the obscure stuff is often much larger than what can be profitably sold through traditional stores alone. While some debate the size of the tail (e.g., whether obscure titles collectively are more profitable for most firms), two facts are critical to keep above this debate: (1) selection attracts customers, and (2) the Internet allows large-selection inventory efficiencies that offline firms can’t match.

The long tail works because the cost of production and distribution drop to a point where it becomes economically viable to offer a huge selection. For Netflix, the cost to stock and ship or stream an obscure foreign film is the same as sending out or streaming the latest blockbuster. The long tail gives the firm a selection advantage (or one based on scale) that traditional stores simply cannot match.

Technology Creates a Data Asset That Delivers Profits

Netflix proves there’s both demand and money to be made from the vast back catalog of film and TV show content. But for the model to work best, the firm needed to address the biggest inefficiency in the movie industry—“audience finding,” that is, matching content with customers. To do this, Netflix leveraged some of the industry’s most sophisticated technology, a proprietary recommendation system. Each time a customer visited Netflix after sending back a DVD, the service essentially asked “So, how did you like the movie?” Today we have a single click (“Like” or “Dislike”) as opposed to the original five-star rating system.

Netflix algorithms generally develop a map of user ratings and steer you toward titles preferred by people with tastes that are most like yours. This is called collaborative filtering and refers to a classification of software that monitors trends among customers and uses this data to personalize an individual customer’s experience. Input from collaborative filtering software can be used to customize the display of a Web page for each user so that an individual is greeted only with those items the software predicts they’ll most likely be interested in. The kind of data mining done by collaborative filtering isn’t just used by Netflix; other sites use similar systems to recommend music, books, even news stories. While other firms also employ collaborative filtering, Netflix has been at this game for years, and is constantly tweaking its efforts. The results are considered the industry gold standard.

Collaborative filtering software is powerful stuff, but is it a source of competitive advantage? Ultimately it’s just math. Difficult math, to be sure, but nothing prevents other firms from working hard in the lab, running and refining tests, and coming up with software that’s as good, or perhaps one day even better than Netflix’s offering. But what the software has created for the early-moving Netflix is an enormous data advantage that is valuable, results yielding, and impossible for rivals to match. More ratings make the system seem smarter, and with more info to go on, Netflix can make more accurate recommendations than rivals.

Understanding Scale & Timing

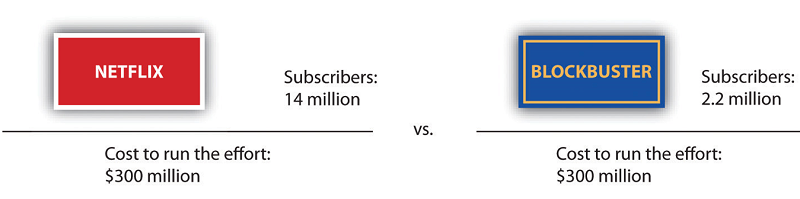

In 2008, the yearly cost to run a Netflix-comparable nationwide delivery infrastructure was about $300 million (Reda & Schulz, 2008). Even if rivals had identical infrastructures, the more profitable firm would be the one with more customers. The firm with better scale economies would be in a position to lower prices, as well as to spend more on customer acquisition, new features, or other efforts. Smaller rivals would have an uphill fight, while established firms that tried to challenge Netflix with a copycat effort were in a position where they were straddling markets, unable to gain full efficiencies from their efforts.

Running a nationwide sales network costs an estimated $300 million a year. But Netflix has several times more subscribers than Blockbuster. History confirms the basic math of which firm’s economies scaled better.

For Blockbuster, the arrival of Netflix played out like a horror film where it was the victim. Pressure from Netflix forced Blockbuster to drop late fees costing it about $400 million (Mullaney, 2006). The Blockbuster store network once had the advantage of scale, but eventually, its many locations were seen as an inefficient and bloated liability. By 2008, Blockbuster had been in the red, meaning it did not make a profit for ten of the prior eleven years. During a three-year period that included the launch of its Total Access DVD-by-mail effort, Blockbuster lost over $4 billion (MacDonald, 2008). Blockbuster tried to outspend Netflix on advertising, even running Super Bowl ads for Total Access in 2007, but a money loser can’t outspend its more profitable rival for long. Blockbuster also couldn’t sustain subscription rates below Netflix’s, so it had to give up its price advantage.

For Netflix, what delivered the triple scale advantage of the largest selection; the largest network of distribution centers; the largest customer base; and the firm’s industry-leading strength in brand and data assets? Moving first. Timing and technology don’t always yield a sustainable competitive advantage, but in this case, Netflix leveraged both to craft what seems to be an extraordinarily valuable pool of assets that continue to grow and strengthen over time.

The Case of Netflix and Amazon Web Services

The following video was shared on the Amazon Web Services (AWS) YouTube Channel in 2015. “Netflix, one of the world’s leading Internet television networks, is using AWS to deliver billions of hours of content monthly, and run its analytics platform for optimum performance of its global service.” Consider, how Amazon, the e-commerce giant that grew from a bookseller into the “everything store” had to develop all these new technologies to scale and grow is able to sell the same technology to its competition in order to facilitate their delivery of products and services.

Watch the following and note key points about scale

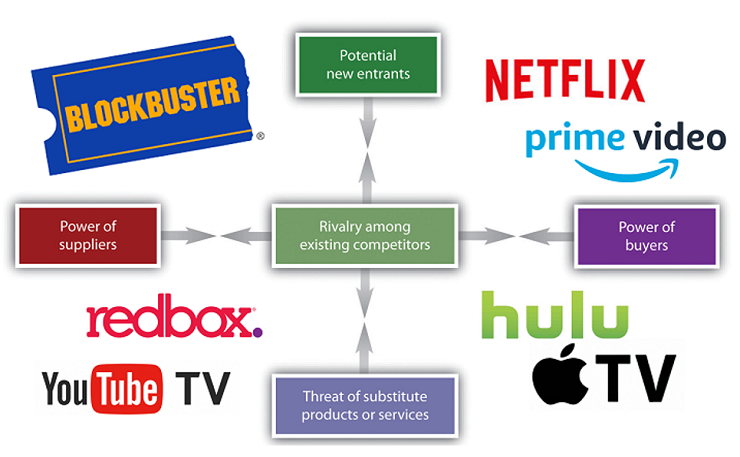

Discuss how Porter’s theory about competitive advantage comes into play in the streaming media field.

- Which is the best provider and why?

- What factors influence your choice as a buyer?

- What are potential threats to your top pick?

- How does rivalry help the buyer?

- What is the role of the supplier here?

Additional References

Boyle, M., “Questions for…Reed Hastings,” Fortune, May 23, 2007.

Conlin, M., “Netflix: Flex to the Max,” BusinessWeek, September 24, 2007.

MacDonald, N., “Blockbuster Proves It’s Not Dead Yet,” Maclean’s, March 12, 2008.

McCarthy, B., “Netflix, Inc.” (remarks, J. P. Morgan Global Technology, Media, and Telecom Conference, Boston, May 18, 2009).

Mullaney, T., “Netflix: The Mail-Order House That Clobbered Blockbuster,” BusinessWeek, May 25, 2006.

Patterson, B., “Netflix Prize Competitors Join Forces, Cross Magic 10-Percent Mark,” Yahoo! Tech, June 29, 2009.

Reda S. and D. Schulz, “Concepts that Clicked,” Stores, May 2008.

Thompson, C., “If You Liked This, You’re Sure to Love That,” New York Times, November 21, 2008.

LICENSE

Tech and Timing: Creating Killer Assets by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.