17.3 – Political Behavior in Organizations

- How do managers cope effectively with organizational politics?

Closely related to the concept of power is the equally important topic of politics. In any discussion of the exercise of power—particularly in intergroup situations—a knowledge of basic political processes is essential. We will begin our discussion with this in mind. Next, on the basis of this analysis, we will consider political strategies for acquiring, maintaining, and using power in intergroup relations. Finally, we look at ways to limit the impact of political behavior in organizations.

What Is Politics?

Perhaps the earliest definition of politics was offered by Lasswell, who described it as who gets what, when, and how.15 Even from this simple definition, one can see that politics involves the resolution of differing preferences in conflicts over the allocation of scarce and valued resources. Politics represents one mechanism to solve allocation problems when other mechanisms, such as the introduction of new information or the use of a simple majority rule, fail to apply. For our purposes here, we will adopt Pfeffer’s definition of politics as involving “those activities taken within organizations to acquire, develop, and use power and other resources to obtain one’s preferred outcomes in a situation in which there is uncertainty or dissensus about choices.”16

In comparing the concept of politics with the related concept of power, Pfeffer notes:

If power is a force, a store of potential influence through which events can be affected, politics involves those activities or behaviors through which power is developed and used in organizational settings. Power is a property of the system at rest; politics is the study of power in action. An individual, subunit or department may have power within an organizational context at some period of time; politics involves the exercise of power to get something accomplished, as well as those activities which are undertaken to expand the power already possessed or the scope over which it can be exercised.17

In other words, from this definition it is clear that political behavior is activity that is initiated for the purpose of overcoming opposition or resistance. In the absence of opposition, there is no need for political activity. Moreover, it should be remembered that political activity need not necessarily be dysfunctional for organization-wide effectiveness. In fact, many managers often believe that their political actions on behalf of their own departments are actually in the best interests of the organization as a whole. Finally, we should note that politics, like power, is not inherently bad. In many instances, the survival of the organization depends on the success of a department or coalition of departments challenging a traditional but outdated policy or objective. That is why an understanding of organizational politics, as well as power, is so essential for managers.

Intensity of Political Behavior

Contemporary organizations are highly political entities. Indeed, much of the goal-related effort produced by an organization is directly attributable to political processes. However, the intensity of political behavior varies, depending upon many factors. For example, in one study, managers were asked to rank several organizational decisions on the basis of the extent to which politics were involved.18 Results showed that the most political decisions (in rank order) were those involving interdepartmental coordination, promotions and transfers, and the delegation of authority. Such decisions are typically characterized by an absence of established rules and procedures and a reliance on ambiguous and subjective criteria.

On the other hand, the managers in the study ranked as least political such decisions as personnel policies, hiring, and disciplinary procedures. These decisions are typically characterized by clearly established policies, procedures, and objective criteria.

On the basis of findings such as these, it is possible to develop a typology of when political behavior would generally be greatest and least. This model is shown in Exhibit 17.4. As can be seen, we would expect the greatest amount of political activity in situations characterized by high uncertainty and complexity and high competition among employees or groups for scarce resources. The least politics would be expected under conditions of low uncertainty and complexity and little competition among employees over resources.

Reasons for Political Behavior

Following from the above model, we can identify at least five conditions conducive to political behavior in organizations.19 These are shown in Table 17.2, along with possible resulting behaviors. The conditions include the following:

- Ambiguous goals. When the goals of a department or organization are ambiguous, more room is available for politics. As a result, members may pursue personal gain under the guise of pursuing organizational goals.

- Limited resources. Politics surfaces when resources are scarce and allocation decisions must be made. If resources were ample, there would be no need to use politics to claim one’s “share.”

- Changing technology and environment. In general, political behavior is increased when the nature of the internal technology is nonroutine and when the external environment is dynamic and complex. Under these conditions, ambiguity and uncertainty are increased, thereby triggering political behavior by groups interested in pursuing certain courses of action.

- Nonprogrammed decisions. A distinction is made between programmed and nonprogrammed decisions. When decisions are not programmed, conditions surrounding the decision problem and the decision process are usually more ambiguous, which leaves room for political maneuvering. Programmed decisions, on the other hand, are typically specified in such detail that little room for maneuvering exists. Hence, we are likely to see more political behavior on major questions, such as long-range strategic planning decisions.

- Organizational change. Periods of organizational change also present opportunities for political rather than rational behavior. Efforts to restructure a particular department, open a new division, introduce a new product line, and so forth, are invitations to all to join the political process as different factions and coalitions fight over territory.

Because most organizations today have scarce resources, ambiguous goals, complex technologies, and sophisticated and unstable external environments, it seems reasonable to conclude that a large proportion of contemporary organizations are highly political in nature.20 As a result, contemporary managers must be sensitive to political processes as they relate to the acquisition and maintenance of power in organizations. This brings up the question of why we have policies and standard operating procedures (SOPs) in organizations. Actually, such policies are frequently aimed at reducing the extent to which politics influence a particular decision. This effort to encourage more “rational” decisions in organizations was a primary reason behind Max Weber’s development of the bureaucratic model. That is, increases in the specification of policy statements often are inversely related to political efforts, as shown in Exhibit 17.5. This is true primarily because such actions reduce the uncertainties surrounding a decision and hence the opportunity for political efforts.

| Conditions Conducive to Political Behavior | |

|---|---|

| Prevailing Conditions | Resulting Political Behaviors |

| Ambiguous goals | Attempts to define goals to one’s advantage |

| Limited resources | Fight to maximize one’s share of resources |

| Dynamic technology and environment | Attempts to exploit uncertainty for personal gain |

| Nonprogrammed decisions | Attempts to make suboptimal decisions that favor personal ends |

| Organizational change | Attempts to use reorganization as a chance to pursue own interests and goals |

Technology, Innovation, and Politics in Performance Appraisals

Developing a strategy for a performance appraisal is an important step for any company, and keeping out political bias is a main concern as well. Unfortunately, many times there is no way around bringing some bias into a performance appraisal situation. Managers often think of the impact that their review will have on the employee, how it will affect their relationship, and what it means for their career in the future. There are a lot of games played in the rating process and whether managers admit it or not, they may be guilty of playing them. Many companies, such as Adobe, are looking at ways that they can revamp the process to eliminate potential biases and make evaluations fairer.

In 2012, Adobe transformed its business, changing its product cycle; while undergoing process changes, Adobe understood that there needed to be a cultural shift as well. It announced the “Check-in” review process to allow for faster feedback, as well as an end to their outdated annual review process. With the faster-paced reality of their product cycles and subscription-based model in technology, this made complete sense.

This process established a new way of thinking, allowing for two-way communication to become the norm between managers and employees. They were able to have frequent candid conversations, approaching the tough subjects in order make improvements rather than waiting until an annual review and letting bad performance go unchecked or good performance go unnoticed. Eliminating a once-a-year cycle of review also eliminates the issue of politics creeping into the process. Managers are able to think critically about the performance, working alongside their employees to better the outcome rather than worrying about having a tough conversation and the bad result that may follow—and having to live with the fallout. Employees also are given chances to provide feedback and their own personal evaluation, which then is discussed with the manager. They review the items together, and what is formally submitted is agreed upon, rather than set in stone. The addition of the employee feedback is another great way to reduce the insertion of politics or bias in the review.

In result of this change, Adobe’s employees showed higher engagement and satisfaction with their work, consistently improving. They no longer had negative surprises in their annual review and were able to adjust priorities and behaviors to become more effective workers.

- What are important considerations to eliminate potential political bias in a performance review?

- Why was Adobe successful in the changes that they implemented in their performance review process?

- What other positive outcomes could be achieved from an ongoing feedback model versus annual performance review?

Sources: D. Morris, “Death of the Performance Review: How Adobe Reinvented Performance Management and Transformed its Business,” World at Work Journal, Second Quarter, 2016, https://www.adobe.com/content/dam/acom/en/aboutadobe/pdfs/death-to-the-performance-review.pdf; “How Adobe retired performance reviews and inspired great performance,” Adobe website, accessed January 4, 2019, https://www.adobe.com/check-in.html; K. Duggan, “Six Companies That Are Redefining Performance Management,” Fast Company, December 15, 2015, https://www.fastcompany.com/3054547/six-companies-that-are-redefining-performance-management.

Political Strategies in Intergroup Relations

Uo this point, we have explained the related concepts of power and politics primarily as they relate to interpersonal behavior. When we shift our focus from the individual or interpersonal to the intergroup level of analysis, the picture becomes somewhat more complicated. In developing a portrait of how political strategies are used to attain and maintain power in intergroup relations, we will highlight two major aspects of the topic. The first is the relationship between power and the control of critical resources. The second is the relationship between power and the control of strategic activities. Both will illustrate how subunit control leads to the acquisition of power in organizational settings.

Power and the Control of Critical Resources

On the basis of what has been called the resource dependence model, we can analyze intergroup political behavior by examining how critical resources are controlled and shared.21 That is, when one subunit of an organization (perhaps the purchasing department) controls a scarce resource that is needed by another subunit (for example, the power to decide what to buy and what not to buy), that subunit acquires power. This power may be over other subunits within the same organization or over subunits in other organizations (for example, the marketing units of other companies that are trying to sell to the first company). As such, this unit is in a better position to bargain for the critical resources it needs from its own or other organizations. Hence, although all subunits may contribute something to the organization as a whole, power allocation within the organization will be influenced by the relative importance of the resources contributed by each unit. To quote Salancik and Pfeffer,

Subunit power accrues to those departments that are most instrumental in bringing or in providing resources which are highly valued by the total organization. In turn, this power enables these subunits to obtain more of those scarce and critical resources allocated within the organization.

Stated succinctly, power derived from acquiring resources is used to obtain more resources, which in turn can be employed to produce more power—“the rich get richer.”22

To document their case, Salancik and Pfeffer carried out a major study of university budget decisions. The results were clear. The more clout a department had (measured in terms of the department’s ability to secure outside grants and first-rate graduate students, plus its national standing among comparable departments), the easier it was for the department to secure additional university resources. In other words, resources were acquired through political processes, not rational ones.23

Power and the Control of Strategic Activities

In addition to the control of critical resources, subunits can also attain power by gaining control over activities that are needed by others to complete their tasks. These critical activities have been called strategic contingencies. A contingency is defined by Miles as “a requirement of the activities of one subunit that is affected by the activities of other subunits.”24 For example, the business office of most universities represents a strategic contingency for the various colleges within the university because it has veto or approval power over financial expenditures of the schools. Its approval of a request to spend money is far from certain. Thus, a contingency represents a source of uncertainty in the decision-making process. A contingency becomes strategic when it has the potential to alter the balance of interunit or interdepartmental power in such a way that interdependencies among the various units are changed.

Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is to consider the example of power distribution in various organizations attempting to deal with a major source of uncertainty—the external environment. In a classic study by Lawrence and Lorsch, influence patterns were examined for companies in three divergent industries: container manufacturing, food processing, and plastics. It was found that in successful firms, power distribution conformed to the firm’s strategic contingencies. For example, in the container-manufacturing companies, where the critical contingencies were customer delivery and product quality, the major share of power in decision-making resided in the sales and production staffs. In contrast, in the food-processing firms, where the strategic contingencies focused on expertise in marketing and food sciences, major power rested in the sales and research units. In other words, those who held power in the successful organizations were in areas that were of central concern to the firm and its survival at a particular time. The functional areas that were most important for organizational success were under the control of the decision makers. For less-successful firms, this congruence was not found.

The changing nature of strategic contingencies can be seen in the evolution of power distribution in major public utilities. Many years ago, when electric companies were developing and growing, most of the senior officers of the companies were engineers. Technical development was the central issue. More recently, however, as utilities face greater litigation, government regulation, and controversy over nuclear power, lawyers are predominant in the leadership of most companies. This example serves to emphasize that “subunits could inherit and lose power, not necessarily by their own actions, but by the shifting contingencies in the environment confronting the organization.”25

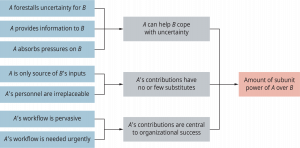

To better understand how this process works, consider the model shown in Exhibit 17.6. This diagram suggests that three factors influence the ability of one subunit (called A) over another (called B). Basically, it is argued that subunit power is influenced by (1) A’s ability to help B cope with uncertainty, (2) the degree to which A offers the only source of the required resource for B, and (3) the extent to which A’s contributions are central to organizational success. Let us consider each of these separately.

Ability to Cope with Uncertainty. According to advocates of the strategic contingencies model of power, the primary source of subunit power is the unit’s ability to help other units cope with uncertainty. In other words, if our group can help your group reduce the uncertainties associated with your job, then our group has power over your group. As Hickson and his colleagues put it:

Uncertainty itself does not give power; coping gives power. If organizations allocate to their various subunits task areas that vary in uncertainty, then those subunits that cope most effectively with the most uncertainty should have most power within the organization, since coping by a subunit reduces the impact of uncertainty on other activities in the organization, a shock absorber function.26

As shown in Exhibit 17.6 above, three primary types of coping activity relating to uncertainty reduction can be identified. To begin, some uncertainty can be reduced through steps by one subunit to prevent or forestall uncertainty for the other subunit. For example, if the purchasing group can guarantee a continued source of parts for the manufacturing group, it gains some power over manufacturing by forestalling possible uncertainty surrounding production schedules. Second, a subunit’s ability to cope with uncertainty is influenced by its capacity to provide or collect information. Such information can forewarn of probable disruptions or problems, so corrective action can be taken promptly. Many business firms use various forecasting techniques to predict sales, economic conditions, and so forth. The third mechanism for coping with uncertainty is the unit’s ability to absorb pressures that actually impact the organization. For instance, if one manufacturing facility runs low on raw materials and a second facility can supply it with needed materials, this second facility effectively reduces some of the uncertainty of the first facility—and in the process gains influence over it.

In short, subunit A gains power over B subunit if it can help B cope with the contingencies and uncertainties facing it. The more dependent B is upon A to ensure the smooth functioning of the unit, the more power A has over B.

Non-substitutability of Coping Activities. Substitutability is the capacity for one subunit to seek needed resources from alternate sources. Two factors influence the extent to which substitutability is available to a subunit. First, the availability of alternatives must be considered. If a subunit can get the job done using different products or processes, it is less susceptible to influence. In the IBM-compatible personal computer market, for example, there are so many vendors that no one can control the market. On the other hand, if a company is committed to a Macintosh and iPad computing environment, only one vendor (Apple Computer) is available, which increases Apple’s control over the marketplace.

Second, the replaceability of personnel is important. A major reason for the power of staff specialists (personnel managers, purchasing agents, etc.) is that they possess expertise in a specialized area of value to the organization. Consider also a reason for closed-shop union contracts: they effectively reduce the replaceability of workers.

Thus, a second influence on the extent of subunit power is the extent to which subunit A provides goods or services to B for which there are no (or only a few) substitutes. In this way, B needs A in order to accomplish subunit objectives.

Centrality of Coping Activities. Finally, one must consider the extent to which a subunit is of central importance to the operations of the enterprise. This is called the subunit’s work centrality. The more interconnected subunit A is with other subunits in the organization, the more “central” it is. This centrality, in turn, is influenced by two factors. The first is workflow pervasiveness—the degree to which the actual work of one subunit is connected with the work of the subunits. If subunit B cannot complete its own tasks without the help of the work activities of subunit A, then A has power over B. An example of this is an assembly line, where units toward the end of the line are highly dependent upon units at the beginning of the line for inputs.

The second factor, workflow immediacy, relates to the speed and severity with which the work of one subunit affects the final outputs of the organization. For instance, companies that prefer to keep low inventories of raw materials (perhaps for tax purposes) are, in effect, giving their outside suppliers greater power than those companies that keep large reserves of raw materials.

When taken as a whole, then, the strategic contingency model of intergroup power suggests that subunit power is influenced when one subunit can help another unit reduce or cope with its uncertainty, the subunit is difficult to replace, or the subunit is central to continued operations. The more these three conditions prevail, the more power will become vested in the subunit. Even so, it should be recognized that the power of one subunit or group can shift over time. As noted by Hickson and his colleagues, “As the goals, outputs, technologies, and markets of organizations change, so, for each subunit, the values of the independent variables [such as coping with uncertainty, non-substitutability, and centrality] change, and the patterns of power change.”27 In other words, the strategic contingency model suggested here is a dynamic one that is subject to change over time as various subunits and groups negotiate, bargain, and compromise with one another in an effort to secure a more favorable position in the organizational power structure.

MANAGERIAL LEADERSHIP

The Politics of Innovation

A good example of the strategic contingencies approach to the study of power and politics can be seen in a consideration of organizational innovation. It has long been recognized that it is easier to invent something new from outside an organization than to innovate within an existing company. As a result, a disproportionate share of new products originates from small businesses and entrepreneurs, not the major corporations with all the resources to innovate. Why? Much of the answer can be found in politics.

When a person or group has a new idea for a product or service, it is often met with a barrage of resistance from different sectors of the company. These efforts are motivated by the famous “not-invented-here syndrome,” the tendency of competing groups to fight over turf, and the inclination to criticize and destroy any new proposal that threatens to change the status quo. Other groups within the company simply see little reason to be supportive of the idea.

This lack of support—indeed, hostility—occurs largely because within every company there is competition for resources. These resources can include money, power, and opportunities for promotion. As one consultant noted, “One person’s innovation is another person’s failure.” As a result, there is often considerable fear and little incentive for one strategic group within a company to cooperate with another. Because both groups usually need each other for success, nothing happens. To the extent that politics could be removed from such issues, far more energy would be available to capitalize on an innovative idea and get it to market before the competition.

Sources: M. Z. Taylor, The Politics of Innovation, (New York: Oxford University Press), 2017; B. Godin, “The Politics of Innovation: Why Some Countries Are Better Than Others at Science and Technology by Mark Zachary Taylor (review),” Technology and Culture, April 2018; W. Kiechel, “The Politics of Innovation,” Fortune, April 11, 1988, p. 131.

CONCEPT CHECK

- What is politics and political behavior in organizations?

Source contents: Principles of Management and Organizational Behavior. Please visit OpenStax for more details: https://openstax.org/subjects/view-all