2.3 Organizational Designs and Structures

3. Identify different types of organizational structures and their strengths and weaknesses.

A 2017 Deloitte source asked, before answering, “Why has organizational design zoomed to the top of the list as the most important trend in the Global Human Capital Trends survey for two years in a row?”19 The source continued, “The answer is simple: The way high- performing organizations operate today is radically different from how they operated 10 years ago. Yet many other organizations continue to operate according to industrial-age models that are 100 years old or more.”

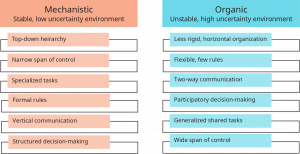

Exhibit 2.3 Mechanistic and Organic Organizations (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC-BY 4.0 license)

Early organizational theorists broadly categorized organizational structures and systems as either mechanistic or organic.21 This broad, generalized characterization of organizations remains relevant. Mechanistic organizational structures (Exhibit 2.3) are best suited for environments that range from stable and simple to low-moderate uncertainty (Exhibit 2.2) and are characterized by top-down hierarchies of control that are rule-based. The chain of command is highly centralized and uses formal authority; tasks are clearly defined and differentiated to be executed by specific specialized experts. Bosses and supervisors have fewer people working directly under them (i.e., a narrow span of control), and the organization is governed by rigid departmentalization (i.e., an organization is divided into different departments that perform specialized tasks according to the departments’ expertise). This form of organization represents a traditional type of structure that evolved in environments that were, as noted above, stable with low complexity. Historically, the U.S. Postal Service and other manufacturing types of industries (Exhibit 4.4) were mechanistic. Again, this type of organizational design may still be relevant, as Exhibit 2.2 suggests, in simple, stable, low-uncertainty environments.

Organic organizational structures and systems, however, have opposite characteristics from mechanistic ones. As Exhibit 2.2 shows, these organizational forms work best in unstable, complex, changing environments. Their structures are flatter, with participatory communication and decision-making flowing in different directions. There is more fluidity and less-rigid ways of performing tasks; there may also be fewer rules. Tasks are more generalized and shared; there is a wider span of control (i.e., more people reporting to managers). Exhibit 2.3 offers examples of organically structured industries, such as high tech, computer, aerospace, and telecommunications industries, that must deal with change and uncertainty. Contemporary corporations and firms engaged in fast-paced, highly competitive, rapidly changing, and turbulent environments are becoming more organic in different ways, as we will discuss in this chapter. However, not every organization or every part of most organizations may require an organic type of structure. Understanding different organizational designs and structures is important to discern when, where, and under what circumstances a type of mechanistic system or part of an organization would be needed. The following section discusses five types of structures with variations.

Types of Organizational Structures

Within the context of mechanistic versus organic structures, specific types of organizational structures in the United States historically evolved over at least three eras, as we discuss here before explaining types of organizational designs. During the first era, the mid-1800s to the late 1970s, organizations were mechanistic self-contained, top-down pyramids.22 Emphasis was placed on internal organizational processes of taking in raw materials, transforming those into products, and turning them out to customers.

Early organizational structures were focused on internal hierarchical control and separate functional specializations in order to adapt to external environments. Structures during this era grouped people into functions or departments, specified reporting relationships among those people and departments, and developed systems to coordinate and integrate work horizontally and vertically. As will be explained, the functional structure evolved first, followed by the divisional structure and then the matrix structured.

The second era started in the 1980s and extended through the mid-1990s. More-complex environments, markets, and technologies strained mechanistic organizational structures. Competition from Japan in the auto industry and complex transactions in the banking, insurance, and other industries that emphasized customer value, demand and faster interactions, quality, and results issued the need for more organic organizational designs and structures.

Communication and coordination between and among internal organizational units and external customers, suppliers, and other stakeholders required higher levels of integration and speed of informational processing. Personal computers and networks had also entered the scene. In effect, the so-called “horizontal organization” was born, which emphasized “reengineering along workflow processes that link organizational capabilities to customers and suppliers.” Ford, Xerox Corp., Lexmark, and Eastman Kodak Company are examples of early adopters of the horizontal organizational design, which, unlike the top-down pyramid structures in the first era, brought flattened hierarchical, hybrid structures and cross-functional teams.

The third era started in the mid-1990s and extends to the present. Several factors contributed to the rise of this era: the Internet; global competition—particularly from China and India with low-cost labor; automation of supply chains; and outsourcing of expertise to speed up production and delivery of products and services. The so-called silos and walls of organizations opened up; everything could not be or did not have to be produced within the confines of an organization, especially if corporations were cutting costs and outsourcing different functions of products to save costs. During this period, further extensions of the horizontal and organic types of structures evolved: the divisional, matrix, global geographic, modular, team-based, and virtual structures were created.

In the following discussion, we identify major types of structures mentioned above and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each, referenced in Exhibit 2.4. Note that in many larger national and international corporations, there is a mix and match among different structures used. There are also advantages and disadvantages of each structure. Again, organizational structures are designed to fit with external environments. Depending on the type of environments from our earlier discussion in which a company operates, the structure should facilitate that organization’s capability to achieve its vision, mission, and goals.

Exhibit 2.4 offers a profile of different structures that evolved in our discussion above.

Exhibit 2.4 Evolution of Organizational Structure Adapted from: Daft, R., 2016, Organization Theory and Design, 12th edition, Cengage learning, Chapter 3; Warren, N., “Hitting the Sweet Spot Between Specialization and Integration in Organizational Design”, People and Strategy, 34, No. 1, 2012, pp. 24-30.

Note the continuum in Exhibit 2.4, showing the earliest form of organizational structure, functional, evolving with more complex environments to divisional, matrix, team-based, and then virtual. This evolution, as discussed above, is presented as a continuum from mechanistic to organic structures—moving from more simple, stable environments to complex, changing ones, as illustrated in Exhibit 2.4. The six types of organizational structures discussed here include functional, divisional, geographic, matrix, networked/team, and virtual.

The functional structure, shown in Exhibit 2.5, is among the earliest and most used organizational designs. This structure is organized by departments and expertise areas, such as R&D (research & development), production, accounting, and human resources. Functional organizations are referred to as pyramid structures since they are governed as a hierarchical, top-down control system.

Exhibit 2.5 Functional Structure (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC-BY 4.0 license)

Small companies, start-ups, and organizations working in simple, stable environments use this structure, as do many large government organizations and divisions of large companies for certain tasks.

The functional structure excels in providing for a high degree of specialization and a simple and straightforward reporting system within departments, offers economies of scale, and is not difficult to scale if and when the organization grows. Disadvantages of this structure include isolation of departments from each other since they tend to form “silos,” which are characterized by closed mindsets that are not open to communicating across departments, lack of quick decision-making and coordination of tasks across departments, and competition for power and resources.

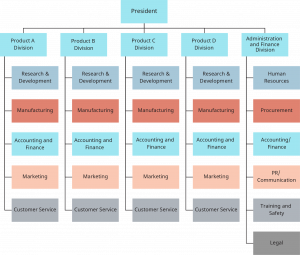

Divisional structures, see Exhibit 2.6, are, in effect, many functional departments grouped under a division head. Each functional group in a division has its own marketing, sales, accounting, manufacturing, and production team. This structure resembles a product structure that also has profit centers. These smaller functional areas or departments can also be grouped by different markets, geographies, products, services, or other whatever is required by the company’s business. The market-based structure is ideal for an organization that has products or services that are unique to specific market segments and is particularly effective if that organization has advanced knowledge of those segments.

Exhibit 2.6 Divisional Organization Structure (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC-BY 4.0 license)

The advantages of a divisional structure include the following: each specialty area can be more focused on the business segment and budget that it manages; everyone can more easily know their responsibilities and accountability expectations; customer contact and service can be quicker; and coordination within a divisional grouping is easier, since all the functions are accessible. The divisional structure is also helpful for large companies since decentralized decision-making means that headquarters does not have to micromanage all the divisions. The disadvantages of this structure from a headquarters perspective are that divisions can easily become isolated and insular from one another and that different systems, such as accounting, finance, sales, and so on, may suffer from poor and infrequent communication and coordination of enterprise mission, direction, and values. Moreover, incompatibility of systems (technology, accounting, advertising, budgets) can occur, which creates a strain on company strategic goals and objectives.

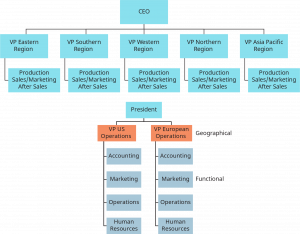

A geographic structure, Exhibit 2.7, is another option aimed at moving from a mechanistic to more organic design to serve customers faster and with relevant products and services; as such, this structure is organized by locations of customers that a company serves. This structure evolved as companies became more national, international, and global. Geographic structures resemble and are extensions of the divisional structure.

Exhibit 2.7 Geographic Structure (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC-BY 4.0 license)

Organizing geographically enables each geographic organizational unit (like a division) the ability to understand, research, and design products and/or services with the knowledge of customer needs, tastes, and cultural differences. The advantages and disadvantages of the geographic structure are similar to those of the divisional structure. Headquarters must ensure effective coordination and control over each somewhat autonomous geographically self-contained structure.

The main downside of a geographical organizational structure is that it can be easy for decision-making to become decentralized, as geographic divisions (which can be hundreds if not thousands of miles away from corporate headquarters) often have a great deal of autonomy.

Matrix structures, illustrated in Exhibit 2.4 and depicted in Exhibit 2.8, move closer to organic systems in an attempt to respond to environmental uncertainty, complexity, and instability. The matrix structure actually originated at a time in the 1960s when U.S. aerospace firms contracted with the government. Aerospace firms were required to “develop charts showing the structure of the project management team that would be executing the contract and how this team was related to the overall management structure of the organization.” As such, employees would be required to have dual reporting relationships—with the government and the aerospace company.25 Since that time, this structure has been imitated and used by other industries and companies since it provides flexibility and helps integrate decision-making in functionally organized companies.

Exhibit 2.8 Matrix Structure (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC-BY 4.0 license)

Matrix designs use teams to combine vertical with horizontal structures. The traditional functional or vertical structure and chain of command maintains control over employees who work on teams that cut across functional areas, creating horizontal coordination that focuses projects that have deadlines and goals to meet within and often times in addition to those of departments. In effect, matrix structures initiated horizontal team-based structures that provided faster information sharing, coordination, and integration between the formal organization and profit-oriented projects and programs.

As Exhibit 2.8 illustrates, this structure has lines of formal authority along two dimensions: employees report to a functional, departmental boss and simultaneously to a product or project team boss. One of the weaknesses of matrix structures is the confusion and conflicts employees experience in reporting to two bosses. To work effectively, employees (including their bosses and project leaders) who work in dual-authority matrix structures require good interpersonal communication, conflict management, and political skills to manage up and down the organization.

Different types of matrix structures, some resembling virtual team designs, are used in more complex environments.26 For example, there are cross-functional matrix teams in which team members from other organizational departments report to an “activity leader” who is not their formal supervisor or boss. There are also functional matrix teams where employees from the same department coordinate across another internal matrix team consisting of, for example, HR or other functional area specialists, who come together to develop a limited but focused common short-term goal. There are also global matrix teams consisting of employees from different regions, countries, time zones, and cultures who are assembled to achieve a short-term project goal of a particular customer. Matrix team members have been and are a growing part of horizontal organizations that cut across geographies, time zones, skills, and traditional authority structures to solve customer and even enterprise organizational needs and demands.

As part of the next discussed organizational type of structure, networked teams, organizational members in matrix structures must “learn how to collaborate with colleagues across distance, cultures and other barriers. Matrix team members often suffer from the problem of divided loyalties where they have both team and functional goals that compete for their time and attention, they have multiple bosses and often work on multiple teams at the same time. For some matrix team members this may be the first time they have been given accountability for results that are broader than delivery of their functional goals. Some individuals relish the breath and development that the matrix team offers and others feel exposed and out of control.” To succeed in these types of horizontal organizational structures, organizational members “should focus less on the structure and more on behaviors.”

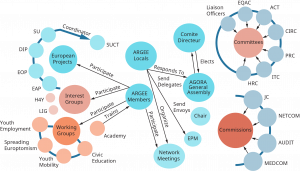

Networked team structures are another form of the horizontal organization. Moving beyond the matrix structure, networked teams are more informal and flexible. “[N]etworks have two salient characteristics: clustering and path length. Clustering refers to the degree to which a network is made up of tightly knit groups while path lengths is a measure of distance—the average number of links separating any two nodes in the network.”28 A more technical explanation can be found in this footnote source.29 For our purposes here, a networked organizational structure is one that naturally forms after being initially assigned. Based on the vision, mission, and needs of a problem or opportunity, team members will find others who can help—if the larger organization and leaders do not prevent or obstruct that process.

There is not one classical depiction of this structure, since different companies initially design teams to solve problems, find opportunities, and discover resources to do so.

Stated another way, “The networked organization is one that is connected together by informal networks and the demands of the task, rather than a formal organizational structure. The network organization prioritizes its ‘soft structure’ of relationships, networks, teams, groups and communities rather than reporting lines.”30 Exhibit 2.9 is a suggested illustration of this structure.

Exhibit 2.9 Networked Team Structure (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC-BY 4.0 license)

A Deloitte source based on the 2017 Global Human Capital Trend study stated that as organizations continue to transition from vertical structures to more organic ones, networked global designs are being adapted to larger companies that require more reach and scope and quicker response time with customers: “Research shows that we spend two orders of magnitude more time with people near our desk than with those more than 50 meters away. Whatever a hierarchical organization chart says, real, day-to-day work gets done in networks. This is why the organization of the future is a ‘network of teams.’”

Advantages of networked organizations are similar to those stated earlier with regard to organic, horizontal, and matrix structures. Weaknesses of the networked structure include the following: (1) Establishing clear lines of communication to produce project assignments and due dates to employees is needed. (2) Dependence on technology—Internet connections and phone lines in particular—is necessary. Delays in communication result from computer crashes, network traffic errors and problems; electronic information sharing across country borders can also be difficult. (3) Not having a central physical location where all employees work, or can assemble occasionally to have face-to-face meetings and check results, can result in errors, strained relationships, and lack of on-time project deliverables.

Virtual structures and organizations emerged in the 1990s as a response to requiring more flexibility, solution-based tasks on demand, fewer geographical constraints, and accessibility to dispersed expertise. Virtual structures are depicted in Exhibit 2.10. Related to so-called modular and digital organizations, virtual structures are dependent on information communication technologies (ICTs).

Exhibit 2.10 Virtual Structure (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC-BY 4.0 license)

These organizations move beyond network team structures in that the headquarters or home base may be the only or part of part of a stable organizational base. Otherwise, this is a “boundaryless organization.” Examples of organizations that use virtual teams are Uber, Airbnb, Amazon, Reebok, Nike, Puma, and Dell. Increasingly, organizations are using different variations of virtual structures with call centers and other outsourced tasks, positions, and even projects.

Advantages of virtual teams and organizations include cost savings, decreased response time to customers, greater access to a diverse labor force not encumbered by 8-hour workdays, and less harmful effects on the environment. “The telecommuting policies of Dell, Aetna, and Xerox cumulatively saved 95,294 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions last year, which is the equivalent of taking 20,000 passenger vehicles off of the road.”34 Disadvantages are social isolation of employees who work virtually, potential for lack of trust among employees and between the company and employees when communication is limited, and reduced collaboration among separated employees and the organization’s officers due to lack of social interaction.

In the following section, we turn to internal organizational dimensions that complement structure and are affected by and affect external environments.

CONCEPT CHECK

1. Why does the matrix structure have a dual chain of command?

2. How does a matrix structure increase power struggles or reduce accountability?

3. What are the advantages of committees?

Source contents: Principles of Management and Organizational Behavior. Please visit OpenStax for more details: https://openstax.org/subjects/view-all