Chapter 5: The Rock Cycle

Learning Objectives

The goals of this chapter are to:

- Recognize three rock types and how they form

- Compare and contrast rock types

- Evaluate the distribution of rock types in North America

5.1 The Rock Cycle

Rocks are solid materials that are primarily made up of minerals. Most of the time, rocks are a combination of minerals that are held together, and sometimes rocks can be made up of just one mineral (not a single mineral crystal, but many crystals of the same type held together). There are three rock types:

- Igneous rocks form when magma or lava cools and solidifies

- Sedimentary rocks form when pieces of weathered and eroded rocks are cemented together, or when minerals precipitate from a solution

- Metamorphic rocks form when pre-existing rocks are altered by heat and/or pressure.

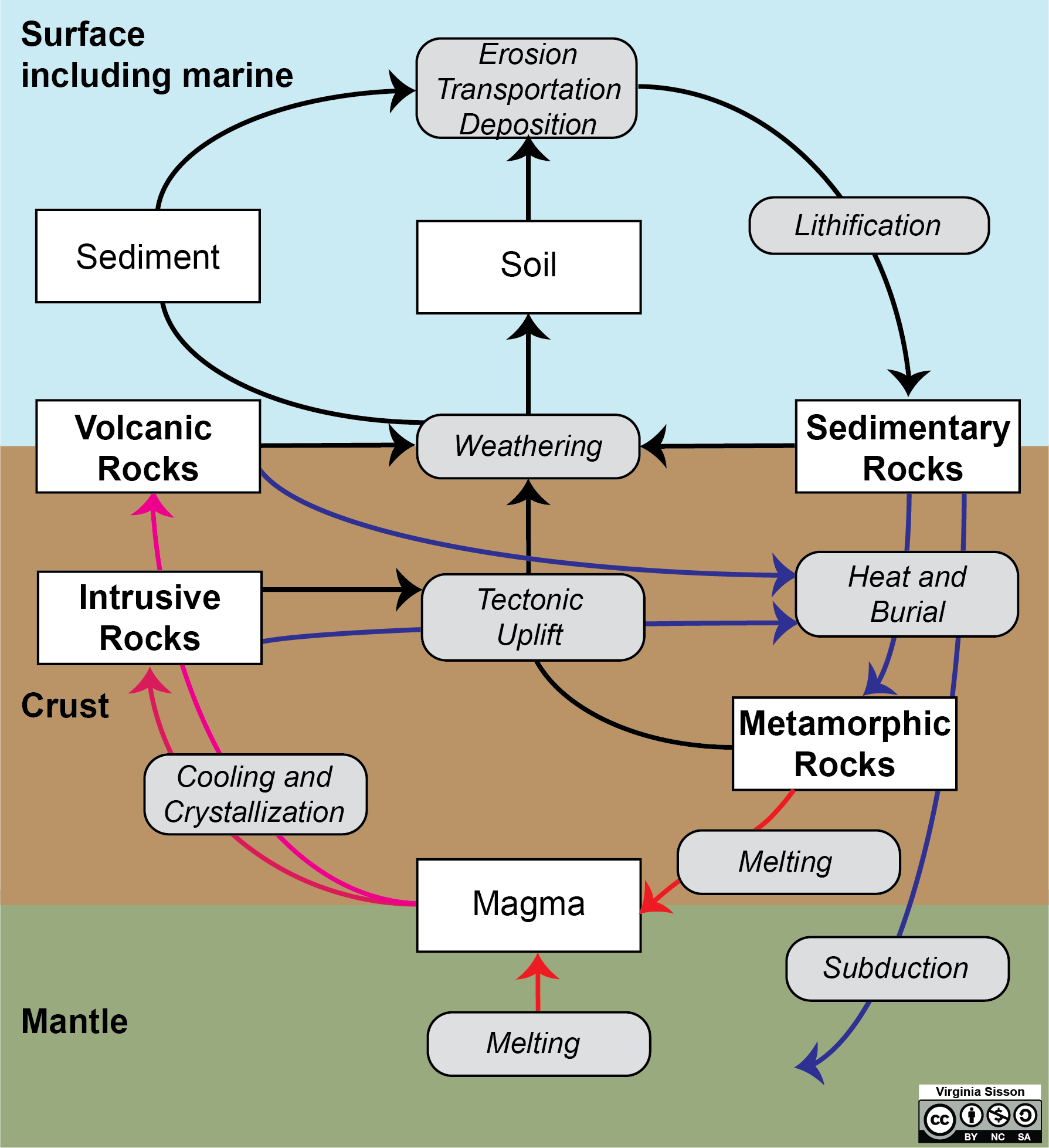

Plate tectonics and other natural processes slowly change rocks from one type to another. The rock cycle (Figure 5.1) is the traditional way geologists have shown the relationships between rock types, including the processes that tie them together. These processes result in distinctive textures, a term geologists use to describe the size, shape, and arrangement (or fabric) of mineral grains in rocks. Broadly speaking, igneous and metamorphic rocks have a crystalline texture, meaning the minerals are interlocking and intertwined with each other. In igneous rocks, the mineral grains are randomly oriented, but in most metamorphic rocks, the mineral grains have a preferred orientation. Sedimentary rocks mainly have a clastic texture, where mineral grains are separated by cement.

Exercise 5.1 – Recognizing Rock Textures

Your instructor has given you three different rocks.

5.2 Rock Formation

Igneous rocks form as magma or lava (molten rock) cools off and solidifies. As the magma cools, minerals crystallize, growing intertwined with each other and forming an interlocking, or crystalline, texture. If the magma cools slowly within the Earth, mineral crystals can grow fairly large (you can see them without magnification), forming an intrusive igneous rock. If magma erupts onto the surface, it’s called lava. Since lava is at Earth’s surface, it cools rapidly and mineral crystals cannot grow very large (you would need magnification to see most of the minerals), or minerals may not even grow at all.

When rocks are exposed at the surface they begin to break apart physically and chemically through weathering processes. These particles that break off are called sediment. Weathering can also produce soil (sediment with organic matter). Sediment is transported and deposited by wind, water, or ice. As sediment accumulates, those at the bottom are compressed and water is squeezed out of the pore spaces. During this process, new minerals can precipitate in the pore spaces that act as a cement to hold the grains of sediment together, giving us sedimentary rocks. Sedimentary rocks can also form when minerals precipitate out of a solution and undergo the same processes.

Metamorphic rocks form when pre-existing rocks are changed by heat and pressure. Through tectonic processes, igneous, sedimentary, and even other metamorphic rocks can be buried deep within Earth’s crust where temperature and pressure is much higher. As these rocks are heated up and squeezed, minerals undergo physical and chemical changes to create metamorphic rocks. If this process continues, these rocks may start to melt which starts the cycle over again with igneous rocks.

Exercise 5.2 – Understanding Rock Formation and Textures

In this exercise, you will learn how rocks form using analogues. Your instructor will provide demonstrations and ask you to make observations and/or sketches. You can also use open-access materials with chocolate or crayons to demonstrate how rocks form.

Observations and sketch from the igneous rock experiment:

Observations and sketch from the sedimentary rock experiment:

Observations and sketch from the metamorphic rock experiment:

Over the next several lab classes, you’ll be asked to identify rocks. The first step to identify a rock is to categorize the rock into one of the three main types or groups of rocks. Igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rock types are distinguished by the processes which form them. Some of the observations you need to make are similar to minerals, such as color, but others such as cleavage and hardness only apply to minerals within rocks. For many rocks, texture is what distinguishes them from other types of rocks.

Exercise 5.3 – Determining Rock Types

Your instructor has given you a set of rocks. Using your knowledge of how rocks form and their textures, classify your rocks as igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic. Fill in Table 5.1.

| Igneous Rock Samples | Sedimentary Rock Samples | Metamorphic Rock Samples |

|

|

5.3 Why Study Rocks?

Why should you study different types of rocks? Well, they all contain clues about what the Earth was like in the past. Perhaps one area may have sedimentary rocks which experienced an environmental change from a desert to a swamp to a coral reef under the sea. Different rocks form under only certain conditions, and even the dullest gray rock can tell us something important about the past. Some types of things that rocks can tell us about our planet as well as other planets are:

- Was there a lake or a volcano present where the rock was found?

- Was there a mountain range or a sea?

- Was it hot or cold?

- Was the atmosphere thick or thin?

For example, by understanding where volcanos have occurred in the past, we have a much better idea of where they are likely to occur in the future and can be prepared for them. Second, by gaining an understanding of how planets work, we can better predict how the Earth will react to changes. If we understand how the Earth and its life responded to temperature changes in the past, we might better understand the effects of the global warming that is happening today.

So the basic point is to better understand our world. This helps us to better coexist with nature and reap the benefits that it has to offer.

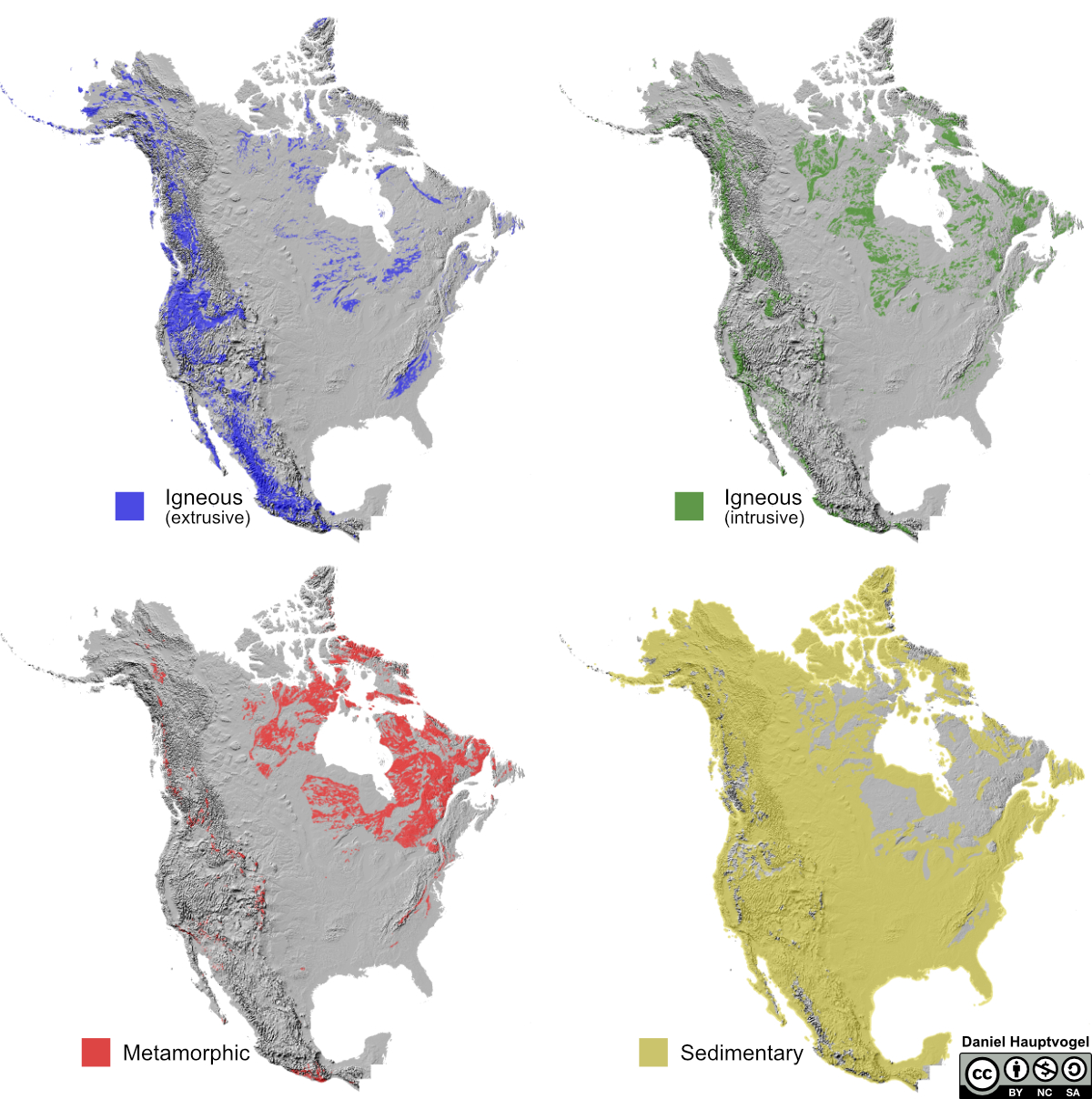

Exercise 5.4 – Rock Types in North America

Look at the distribution of rock types at the surface in North America (Figure 5.6) and answer the following questions. Remember that these maps show you rocks at the surface of the Earth.

- What is the most abundant rock type in North America? ___________________

- Describe the distribution of each rock type. For example, do you see any patterns or are those rocks only located in certain areas?

- Critical Thinking: These maps only show what is exposed is at the surface. Why does one rock type cover most of North America?

- Critical Thinking: Cratons are the nuclei of continental plates composed of intrusive igneous and metamorphic rocks. Where do you think the craton of North America is located? What is your reasoning?

Another reason to study rocks is that they have many industrial uses and are an essential part of the world’s economies. They are used in their natural state as raw materials, or as additives in a wide range of applications. Typical examples of industrial rocks are limestone, marble, granite, unlithified sediment such as clay, sand, gravel, and less well-known rocks such as diatomite, trona, and bentonite. These are used in construction, ceramics, paints, electronics, filtration, plastics, glass, detergents, and paper. In 2025, the U.S. Geological Survey reported that the United States exported ~$11 billion in resources. More importantly, domestic uses of rocks added up to $106 billion as ores, sand, gravel and stone. The total value to the gross domestic product (GDP) was $4,080 billion. So, knowing about the rock cycle will help the world’s economies.

Exercise 5.5 – Industrial Uses of Rocks

- Take a selfie picture of yourself with an industrial rock. If you have never looked for these, look at sculptures carved from rocks. Or look at your home, dorm, or classroom building (e.g., walls, countertops, roof, steps, etc). If your classroom is old, it may have a chalkboard made of slate, a metamorphic rock.

- Describe your industrial rock.

- What type of rock is this?

- Table 5.2 contains a list of commercial materials made from rocks. Use the internet to search for the types of rock(s) that create these commercial materials. For the rock type, you can list the specific rock name, such as slate, or the general classification, such as metamorphic. Some of these commercial materials derive from more than one rock type. Then, determine where the rock is commonly mined.

Table 5.2 – Commercial Materials in the Rock Cycle Commercial Material Rock Type (s) Where do you find it? Any other useful information? Aggregate/crushed stone Stone for sculptures Stone for tombstones Sand for fracturing rocks Wallboard Salt Building stone Concrete Counter tops Glass Ceramics (pottery) Fertilizer Fireplace or grill rocks Pumice for skin care Cat litter Zeolite for water purification Baking soda

Additional Information

Reference

U.S. Geological Survey, 2025, Mineral commodity summaries 2025 (ver. 1.2, March 2025): U.S. Geological Survey, 212 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/mcs2025.

Exercise Contributions

Daniel Hauptvogel, Virginia Sisson

A series of processes which relate rocks in Earth, including igneous intrusion or extrusion, weathering, erosion, transport, deposition as sediment, which lithifies into sedimentary rock, metamorphism, remelting, and leading again to igneous activity