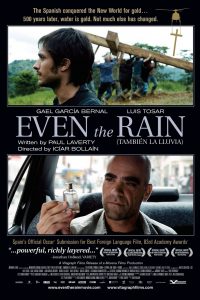

20 También la lluvia. Dir. Iciar Bollaín, 2010

Extra Credits for this week.

Bartolomé de las Casas and 500 Years of Racial Injustice Brief presentation, that’s only 6 minutes. A paragraph summarizing the contents can add up to 10 pts to one of your assignments

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1XmuQvvqsZU

The other extra credit is a full-length movie in English – The Mission (dir. Roland Joffé, 1986) When a Spanish Jesuit goes into the South American wilderness to build a mission in the hope of converting the Indians of the region, a slave hunter is converted and joins his mission. It’s widely available. Again, a couple of paragraphs with your reaction will add 10 pts to any assignment.

Paper read by Dr. Soliño at the Annual Conference of the Asociación Internacional de Literatura y Cultura Femenina Hispánica – Pomona College, October 11, 2013

Please pardon that this chapter is in English.

Iciar Bollaín’s También la lluvia

Neo-colonialism and the Parodies of Empire

In one of the most poignant films of 2010, Iciar Bollaín’s También la lluvia, an international crew arrives in the Cochabamba region of Bolivia to film a new historical epic film about the landing of Christopher Columbus and the first stages of the Conquest. These include the Mexican director, played by Mexican actor Gael García Bernal, and the Spanish producer, played by Luis Tosar, working with hundreds of indigenous extras. Their initial intention is to refocus the story of the Conquest lending

about the landing of Christopher Columbus and the first stages of the Conquest. These include the Mexican director, played by Mexican actor Gael García Bernal, and the Spanish producer, played by Luis Tosar, working with hundreds of indigenous extras. Their initial intention is to refocus the story of the Conquest lending

it the nuances that earlier productions of the Columbus story lacked, mainly by inserting the discourses of the two most notable voices against the abuse of the indigenous population – Antonio Montesinos and Bartolomé de las Casas.

Here is an exerpt from the sermon Montesinos preached:

Instead, through the actions of the crew, as well as the local government that prevents the indigenous population from even collecting rainwater, the film develops into a denunciation of the continued colonization of Latin America, today by local neo-liberal governments and the multinational corporations with whom they collaborate. In a neo-liberal state, the deregulation of business and the privatization of certain industries allows some individuals and corporations to get richer, while the average citizens are left to fend for themselves, often without government protection. One extreme, but sadly common impact of the privatization by the neo-liberal state, is when people no longer have access to clean water because the government has sold the water supplies to a multinational corporation. In historical reality, this happened in Bolivia and many other places. The Austrian CEO of Nestle,Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, declared that access to water is not a basic human right, that water is a marketable commodity like any other product. Thus in 2011 Nestle made a profit of over 68,580 million euros, while people in Latin America were asked to pay a high percentage of their income just on water. This is particularly offensive in that the corporations who profit are often European, and those who suffer are often indigenous, thus reproducing the old colonial system.

In También la lluvia, while the fictional crew is filming their revisionist historical epic, their lead indigenous actor, Daniel, becomes one of the leaders in the Guerra del agua, the real-life series of riots that rocked Cochabamba between January and April 2000 due to the privatization of the water supply which local governments had sold to Bechtel, an American and British multinational. Many Bolivians were only making an average of $100 a month, and were suddenly asked to spend $20 a month on water. $20 a month seemed like a small fee to the Europeans and North Americans, as well as influential Bolivian politicians, who would profit from the sufferings of the average Bolivian. These were not just normal water bills. How would you react if Governor Abbott sold all of Texas’s water to a German corporation, and as a result you have to pay 25% of your family income on water? And they wouldn’t even let you collect rain water. That’s what happened to the people of Cochabamba.

These riots were significant not only at the local level, but took on world significance as a successful anti-globalization movement. To emphasize the veracity of these events, Bollaín inserts news footage of the actual riots into her film, with the grainy black and white images contrasting sharply with the lush colors and textures of the scenes from the conquest being shot just outside the city.

The fictional crew that is supposedly filming the conquest through the eyes of the Tainos that Columbus first encountered, becomes aware of both the riots and the plight of the indigenous extras with whom they work every day, not through human interactions, but through a television in the bar of their hotel. Daniel, the seemingly idealist director who wants to give voice to the conquered and victimized through this film, refuses to acknowledge that now, in the early twenty-first century, Latin American elites, like him continue to perpetuate the abuses. His self-congratulatory attitudes towards their film are revealed as nothing less than aloofness and a narcissism that leads him to believe that their film is more important than the lives of their extras. In a meeting with the mayor of Cochabamba, Daniel reproaches the official for thinking that the people can spend such a high percentage of their salary on something as basic as water, only to be reproached in turn for exploiting the extras by paying them only $2 a day. More than once in the film Daniel justifies the higher purpose of his art by saying: “This confrontation will end and it will be forgotten. But our film is going to last forever.”

In its portrayal of the Cochabamba riots, También la lluvia becomes a graphic visualization of the findings of a 2009 Greenpeace study titled ‘Los nuevos conquistadores: Multinacionales españolas en América Latina — Impactos económicos, sociales y medioambientales’ which details the many abuses of peoples and natural resources being committed by European multinationals in connection with local government. The film exposes one particular case of neo-colonial tactics of multinationals that dominate Latin America. Sadly, the indigenous people hired as extras in También la lluviaare are now doubly colonized by their own local governments, by elites like Daniel, as well as by the multinationals, both those who control even their water supply, as well as the supposedly benevolent filmmakers that hire them as extras, bosting that they can get away with paying them only $2 a day. The location of the filming is dictated by economics. It is the cheapest place to film, and never mind that Columbus never went to Bolivia or that the Tainos did not speak Quechua. To the filmmakers, all indigenous peoples are the same.

In a way, También la lluvia is a comment on the state of the film industry that makes it almost impossible for Latin American, as well as European filmmakers to produce their works without multinational support, bringing the state of neo-colonialism into the film industry through funding entities liker Ibermedia. By 2006 Ibermedia alone had co-produced two hundred and one Latin American films. Although theoretically an international entity, Ibermedia is headquartered in Spain and is staffed mainly by Spaniards. In order to receive much needed funding, Latin American directors are forced to incorporate a quota of Spaniards into their cast and crew. Transatlantic cinema is the term used for the subgroup of transnational films financed with both American and European funding.

Mexican director María Novaro was forced to alter the storyline of her film Sin dejar huella when the backing of TVE (Televisión Española) required her to cast the Spaniard Aitana Sánchez Gijón, instead of the American character that she had originally woven into the script. Whether it is a matter of funding, or of courting the audiences in Spain, the film markets of Spain and Latin American have become intertwined. Bollaín avoided funding from government-backed entities, gaining greater artistic freedom, yet the film ultimately does portray the situation of transatlantic productions. También la lluvia was co-produced by Spain, France, and Mexico. If in the film within the film the producer is Spanish and the director Mexican, También la lluvia itself was written by a Scot, Bollaín’s partner Paul Laverty who had lived for years in Nicaragua, and of course is directed by a Spaniard, with crews from Spain, Mexico, and Bolivia, where the film was shot.

There are multiple and often contrasting interpretations of Christopher Columbus as a historical epic figure, but one element of his life remains unquestioned – There is ample evidence that Columbus was not the first European to explore the New World. Norsemen landed in Greenland and Newfoundland, and it is even likely that African traders had already been to what today is Brazil, and fisherman from Northwest Europe to the islands off the coast of Canada. However none transformed both continents forever as did Columbus’s voyages. (19) For better, and many times for worse, the exchange of ideas, people, plants, products and diseased sparked by Columbus represents for many the “most significant event in human history since the end of the Ice Age” (20).

For centuries the image of Christopher Columbus has been manipulated as a cultural product to either promote the Black Legend abroad, or to encourage national and ethnic pride, not only in Spain, but even in the United States. “The [North] American Columbus is a man of unremarkable origins who accomplished remarkable deeds, whose vision, perseverance, and strength of character were enough to change the world. An example to us all.” (8) This sentiment was so strong among the Founding Fathers of the United States, that they chose to co-name the new capital after him, thus we have Washington linked to him through the added District of Columbia, and Columbus’s name is scattered everywhere along the national landscape from Columbus Circle and Columbia University in NYC, to Columbus, Ohio. When the Italians in the US began to move up from being a poor ethnic minority, to a powerful economic and political force, they chose Christopher Columbus, emphasizing his Genovese origins as their cultural icon.

All these American forces, as well as the Italian and Spanish claims on Columbus as their national hero clashed in the 1980s as a Quincentenary Commission sprung up on both continents to commemorate the 500th anniversary of his first landing. As Stephen Summerhill and John Alexander Williams write in Sinking Columbus: Contested History, Cultural Politics, and Mythmaking during the Quincenternary, “the 1992 Quincentenary succeeded because it failed. Planners set out to celebrate an imperial past but found themselves confronting difficult questions about the rise of colonialism, the destruction of native American societies, and the disruption of biological habitats throughout the globe” (5).

History of Films about the Conquest

The Quincentenary commissions did sponsor some films that are relevant to our reading of También la lluvia, which can best be understood as a disruption in the continuum of films about Columbus and the conquest. From its inception the Spanish film industry produced historical epics to counteract the reality of Spain as a nation that had failed in its project to construct a strong feeling of national unity. The 1917 Colón y su descubrimiento de América, directed by the Swiss-born Gérard Bourgeois, was the first attempt to create a cine nacional. click to see a clip of how happy the indigenous people were to see Columbus in this version of the story. Cine Mudo Colón 3b

That this first historical epic harking back to the glories of the Age of Discovery appears precisely at a time of the national crisis is hardly coincidental. In 1917 Spain suffered through a series of events that foreshadowed its later civil war. There was discontent in the military forces due to the African wars, impasses in the parliament, and social unrest that culminated in a national strike. All of this lead to the imposition of a military totalitarian state in 1923 with the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera.

The Franco regime likewise invented its own mythic Columbus. Juan de Orduña’s Alba de América, which was fully funded by El Consejo de la Hispanidad, and heralded as “La mayor superproducción del cine español” (Primer Plano 17 June 1951), is best-known as the flop that brought down Cifesa’s line of historical epics. Orduña described his film as “el poema del descubrimiento.” It turned out to be the swan song of a cycle of historical epics of the autarchy.

With Alba de América the Franco regime aimed to produce a refutation of the Black Legend version of the Conquest as portrayed in the 1949 British film Christopher Columbus starring Fredric March. The Black Legend is the version of the Spanish Conquest favored by Northern Europeans, especially the British and the Dutch, in which Spaniards are particularly cruel in their conquest. Of course, part of the purpose of the Black Legend is to pretend that Northern Europeans were any less cruel and unjust in their conquests of North America and parts of the Caribbean.

The Spanish government was also deeply offended at the insistence in the British film of Columbus’s Italian nationality, with many in Spain still insisting that he was born in Pontevedra. Yet the use of cinema to solidify Spain’s sense of itself as a unified nation had always been problematic, especially when compared to similar attempts in other countries. As Jean-Claude Seguin points out, when French directors incorporated history into films, their works reintroduced a well-accepted concept of the nation that had evolved over centuries. Somewhat similarly, when U.S. directors celebrated the nation, their works were closely aligned with contemporary ideologies. But in Spain, the nationalist project was far more uncertain. A cinematic fantasy, the longing for national unity, while repeatedly re-enacted on the screen, was at odds with the Spanish reality of profound ideological and regional divisions.

Saura’s 1988 El Dorado (1988) which received generous funding from the Quincentenary Commission, was the first film in years to touch on Spain’s imperialist past but was a flop, and received accusations from the right of highlighting Spain’s Black Legend. It focuses on Lope de Aguirre.

Bollaín is not original in portraying Columbus a ruthless conqueror, guilty of fully exploiting the indigenous people with shocking cruelty. This vision of Columbus was already present in Ridley Scott’s 1492: The Conquest of Paradise which premiered in 1992.

Its very beginning highlights that it will be an unnuanced continuation of the Black Legend when in the opening credits we are told “500 years ago, Spain was a nation gripped by fear and superstition, ruled by the crown and a ruthless Inquisition that persecuted men for daring to dream. One man challenged this power. Driven by his sense of destiny, he crossed the sea of darkness in search of honor, gold, and the greater glory of God.” Within the first few minutes Columbus travels to Salamanca where the audience sees the cruelty of the Inquisition through the eyes of Columbus’s younger son, Fernando. Summerhill and Williams criticize this crop of films because they “clamped a vise on the viewer’s gaze, directing him or her to a narrative that focused on the individual and personal … “ With its focus on Columbus as a foreigner trying to navigate the Spanish court, and the choice to cast Gerard Dépardieu as Columbus, they tried to link Columbus’s plight to that of immigrants so that to those familiar with Dépardieu’s work, it seemed like it was “really Cyrano trying to get his green card” (189). [Two of Dépardieu’s popular films popular in the USA were Cyrano de Bergerac www.dailymotion.com/video/x73hozs and the romantic comedy Green Card about a French man trying to get his green card through a fake marriage. Since it is a romantic comedy, they 2 people involved in the fake marriage realize that they have really fallen in love https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JkB9NBoHrLw]

In También la lluvia Sebas’s version of Columbus is demythicized, although one could argue that he’s making a film that has already been made. The German Werner’s 1972 Aguirre, Wrath of God and Roland Joffé’s 1986 The Mission. Sebastián states that the originality of his project is that he will include the debates already present in the earliest stages of the Conquest. To this end, much of the story features Bartolomé de las Casas and Antonio Montesinos.

De las Casas has become the most important symbol of the cry for justice and human rights in early colonial Latin America. De las Casas had traveled to Española in 1502. Five years later he travels to Rome with Diego and Bartholomew Columbus, son and brother of Columbus, to meet with Pope Julius II; where he is ordained a priest. On his return to La Española with a group of Dominicans, he hears Fr. Antonio de Montesinos’s famous homily condemning the encomienda system. In theory the encomienda system mimicked deudalism. A Spaniard would be granted a large tract of land. The enomendero would be given a certain number of indigenous people to work the land, farming or mining for precious minerals. Rather than being paid for their labor, the indigenous workers would have to produce a certain amount for the encomendero, and then would be paid in “protection and education into the Catholic faith.” They called it the encomienda system because Queen Isabel had outlawed slavery. But it was just slavery by another name. Bartolomé de las Casas was originally an encomendero, but experiencesaconversion 3 years later after hearing Montesino preach. He then returns to Spain with Montesinos to advocate for the rights of the indigenous peoples before King Fernando. If the Conquest were in search of a pair of heroes, Montesinos and the de las Casas, the author of the Brevíssma Relación de la Destruición de las Indias, would certainly fit the bill. Sebastián and Costa focus key scenes of their film on these two facile heroes. However, they leave out the part where de las Casas found a solution in bringing slaves from Africa to relieve the indigenous peoples of their burden. He later changed recognized his error on that front. In También la lluvia there is a shift from the best known films about Columbus and the Conquest, but the flaw is that they are still trying to make a film about the conquest that focuses on creating heroes that would replace Columbus.

Yet, También la lluvia questions, and even parodies the oversimplification of the works of these two priests. One of the most brilliant features of the film is Karra Elejalde’s portrayal of Antón, the actor who plays Columbus. He won the Goya for best supporting actor in this role. Antón is a cynical alcoholic, so estranged from his family that they will not even take his phone calls. He, however, provides the most lucid commentary on their whole venture.

The actor who plays Bartolomé de las Casas excuses him for trying to free up the indigenous people from hard labor, by importing African slaves. He says that de las Casas just made that one big mistake, and that he regretted it all his life. Starting up the African slave trade to the Spanish colonies is too big a mistake for a film about his life to silence. While the film uses Antón’s drunken lucidness to express an alternate point of view that is missing in all the other films about the Conquest, it doesn’t flinch from portraying Columbus’s cruelty. In scenes very similar to those of 1492: The Conquest of Paradise, when the indigenous people cannot provide their quota of gold, the Spaniards chop off their hands. Yet here Columbus is no longer any sort of hero. Sebastián adds the image of Columbus himself, perched high up on his horse, nodding in approval, even giving the order, to carry out the barbaric mutilations.

Another important modification in Bollaín’s film is the role she assigns to the women in the film who are portrayed simultaneously as victims of the Spaniards, as well as elements of change, as they rise up in protest, both as part of the cast, when they refuse to follow Sebastián’s orders, and as they attack the police who come to destroy the well in which they were gathering rain water for their families.

The scene in which the indigenous women of the cast refuse to participate in a scene in which they pretend to drown their babies not only shows the power that women can have, but also brings into question the purpose and validity of graphic reproductions of cruelty. These women refuse to represent the violence of the past, as if with the repetition they stirred up generational traumas, mainly for the entertainment of non-indigenous audiences.

And there is one more woman on the set, María, who is present with a handheld camera to shoot the making-of feature that will accompany the dvd version. However, as she glimpses that the real story to be told is that of the Guerra del agua, she is continually ordered to stop shooting be the male dominated industry. Yet, she is also one of the crew members who when the riots become more violent, abandons Cochabamba without worrying about the fate of the people with whom they had been working. It turns out that to her, this was also just another professional opportunity.

The ending of the film offers of glimmer of hope for future transatlantic collaborations. As the Bolivian city erupts into a riot over the issue of water rights and the film’s cast and crew flee the violence, the Spanish producer stays behind to help the family of one of the indigenous actors. It turns out that Costa has a heart after all, and he has developed a relationship with Daniel’s family. In the end, the indigenous girl survives thanks to the intervention of the Spaniard who has now learned to view his extras as fellow human beings instead of as commodities to be bought for two dollars a day. Most critics note that Costa’s change of heart happens abruptly and unexpectedly at the end of the film, and we now have a narrative of the natives reliant upon a European savior’s intervention to save them … his apparently happy ending may be another choice that Bollaín made to imply the continuity of colonialism through Costa. (253) Yet the ending is not clear. “The successful quincentennial exhibitions and books had in common a feature that might be called ‘narrative indeterminacy.” That is, they allowed viewers or readers freedom to proceed in a nonlinear fashion, to compare discordant objects and ideas and their sources without inherent bias, and to invent or revise Columbian interpretations of their own.” Costa’s humanity at the end – might just as well be a reflection of what could have been, or even of numerous untold stories of the conquest that never became canonical readings.