Beijing

5 北京之春 Analysis by Anonymous 1

Anonymous 1

北京之春

The Legacy and Meaning of the Beijing Spring as Expressed by the Stars

Statement of Purpose

The Beijing Spring is an event that is not quite as well known by those outside of China. However, this event was the catalyst for future protests and pro-democracy movements in Beijing. This event largely took place in the years 1978 and 1979, while the People’s Republic of China (PRC), was under the rule of Deng Xiaoping. Being just soon after the Cultural Revolution, which had ended only a few years earlier in 1976, the scars from such social unrest remained upon the people. The purpose of this essay will be to explore the themes and motives of the artists during this time, as expressed by their artwork, as well as share the stories of the artists and other pro-democracy actors in this movement.

Introduction

One documentary, going quite fittingly by the name Beijing Spring, details the events surrounding a few notable individuals and artists around this time. More specifically, it revolves around a group of artists known as 星星, or the Stars. The group wished to produce art which was somewhat unaccepted at the time within China, such as impressionist or other types. They decided to host an exhibition outside of the National Museum of China, hanging their art from the gates of the fences, nailing it to trees, or simply placing it on the ground in the case of sculptures. Because of this, the group had created quite a controversy. Messages left by visitors had very mixed sentiments, although those highlighted in the documentary were, for the most part, positive. Two pieces from this exhibition, 人民的呼声 (People’s Cry) by Ma Desheng and Old Summer Palace: Rebirth (圆明园) by Huang Rui will be analyzed.

Before this analysis begins, it should be noted that the one bias which is clear and consistent throughout this documentary is that, for the most part, these are the voices of the members of the Stars who left China and Beijing. This does not invalidate, but rather shapes the perspectives and voices of these individuals. It is only something to be kept in mind as the analysis of their works and the events of the Beijing Spring are undertaken.

Part One: Exhibition Art

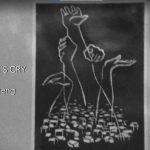

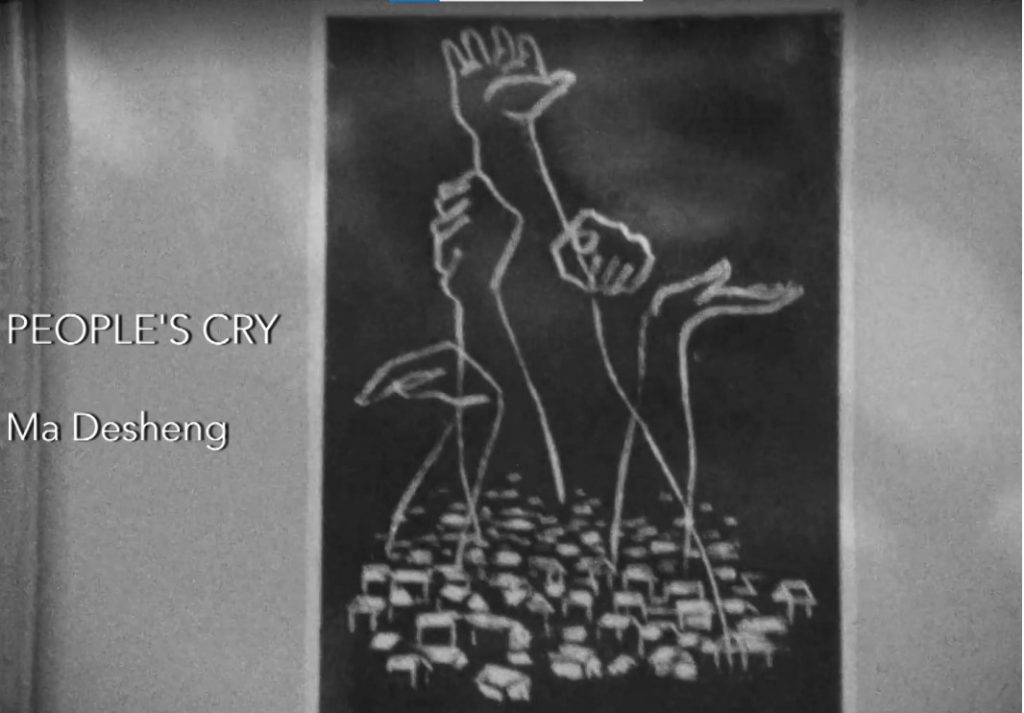

People’s Cry – Ma Desheng

In regard to this work, the artist states: “There was a work called ‘People’s Cry’ There were some little houses below on the painting, Beijing style. Little bungalows. Many hands are stretched out the top. There are angry hands, begging hands, helpless hands. All kinds of hands, accusing hands” (Beijing Spring). While this does come directly from Ma Desheng, the source of this work, it is difficult to accept that this is all there is to this work.

For instance, the choice of color creates a striking image for the viewer. By choosing only two colors, black for the canvas and white for the details, the artist creates a work that is striking despite the amount of empty space. The black is very dark and unknown, eliciting some feeling of dread, especially as the houses below seem to fade away into it. The accusing hand, pointing directly at the viewer does not come from the homes as the other hands do, rather it protrudes from the darkness. Moreover, it seems that all hands are the people’s but this hand, unless it is that of those who have already slipped into the darkness. It could perhaps be those who conduct suppression, or those who are co-conspirators or collaborators of it.

This work appears to me at a high level to be about the struggle for freedom of expression in Beijing. Without it, there is darkness. As it is constricted away from the people, some feel angry, some reach for help, some hope for something in return. Thus, at a deeper level it shows the emotions that people have towards the restriction of freedom of expression within Beijing. Some hope for help, some wish to take action, others ask for something in return.

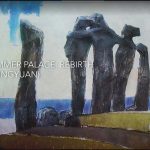

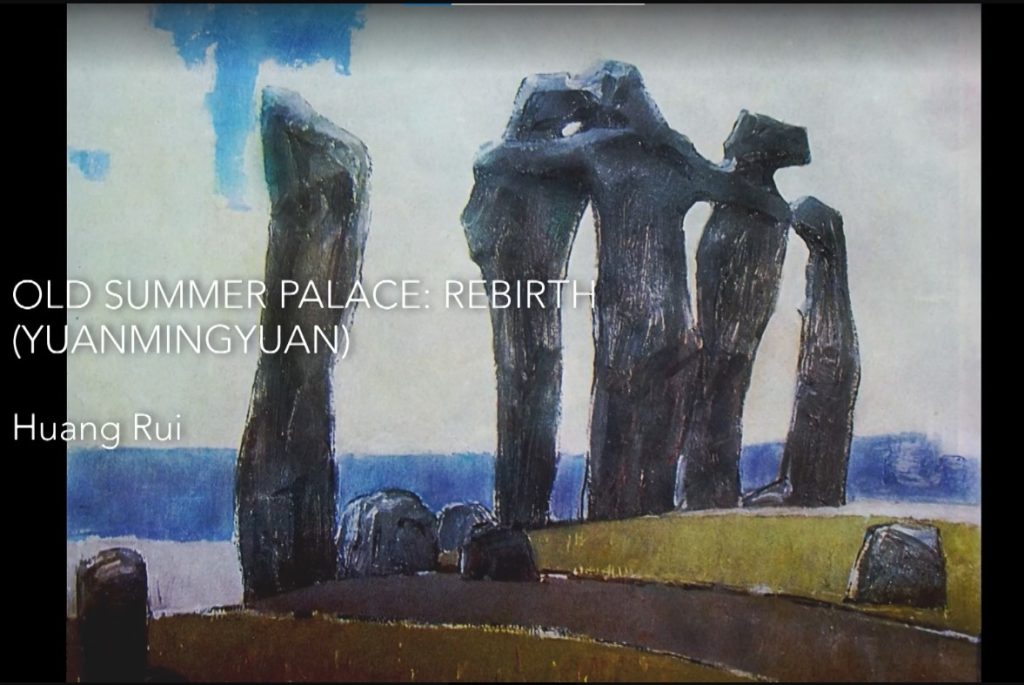

Old Summer Palace: Rebirth – Huang Rui

Cropped due to screenshotting

Another notable work at this exhibition is known as Old Summer Palace: Rebirth and was created by Huang Rui. One quote from the documentary, Beijing Summer, states: “He used the remains of the Old Summer Palace such as doors, stones, pillars, and then he personalized them, depicting human beings. The feeling is supporting each other and standing up. This represents China awakening”. Notably, during Beijing Summer, the Old Summer Palace was a group of ruins which artists frequented to go and paint (Beijing Summer).

Overall, this work establishes in the viewer a feeling of togetherness. There are the people, made of stone, standing near one another, somewhat longing. It is unclear if the leftmost tall stone is meant to represent a person as well as the shape is not quite as clear. But the stones which remain on the group appear like they could create perhaps one more person. Once again, the use of color makes this painting quite striking. In reality, the stones of the Old Summer Palace are not black, they are white. This instills the impression that the artist was hoping to convey the feelings of hardship that they and those around them have suffered. However, although the end of the Cultural Revolution was only shortly before, to speak poorly of this time was not and is not generally accepted.

This work is rather intriguing because of the contrast between the simplicity of expression and how universal the message is, and the reaction that would follow. Moreover, because this area was a place that artists frequently went to paint as previously mentioned, it creates a clear case for how freedom of expression is being limited. Surely, reality can be depicted, unless it is of sensitive events. But, as artists begin to express their feelings and interpret the world around them, it appears to have crossed the line.

The Stars were forced to remove their artwork, under the guise of an issue regarding “social order” (Beijing Spring). The officer who came to the exhibition, simply demanding the artwork be removed, the artist retorted, stating that there was no legal right for this to happen, but the officer insisted nevertheless (Beijing Spring). Then, a sign was erected which prohibited exhibitions in this location. In a sense, this practice of creating some form of plausible deniability became standard to stifle basic individual freedoms. The artists were not told they could not create their artwork, but rather that they could not place it where it was, yet it was clear that the location was not the underlying issue.

Due to the very clear message of this artwork and the reaction that followed, several pieces of information can be retrieved. What can be understood from this piece of artwork (as well as others around it), and the reaction it received is that there was a form of forced amnesia that was beginning. In no way is the idea of rising from ruins or ashes controversial, this is a common form of metaphor. Rather, it was the nature of who the message was directed to and for what reasons that the artwork was restricted.

Furthermore, there is a great irony in the use of color in this piece when combined with the analysis of the use of color in Ma Desheng’s People’s Cry. In the previous artwork, it was analyzed to show how the darkness is a form of restriction or oppression. By extension into this piece, as the work was censored, it truly was the emotions of the people being censored and restricted, giving new meaning to the use of color in this piece.

Part Two: Post Exhibition Art

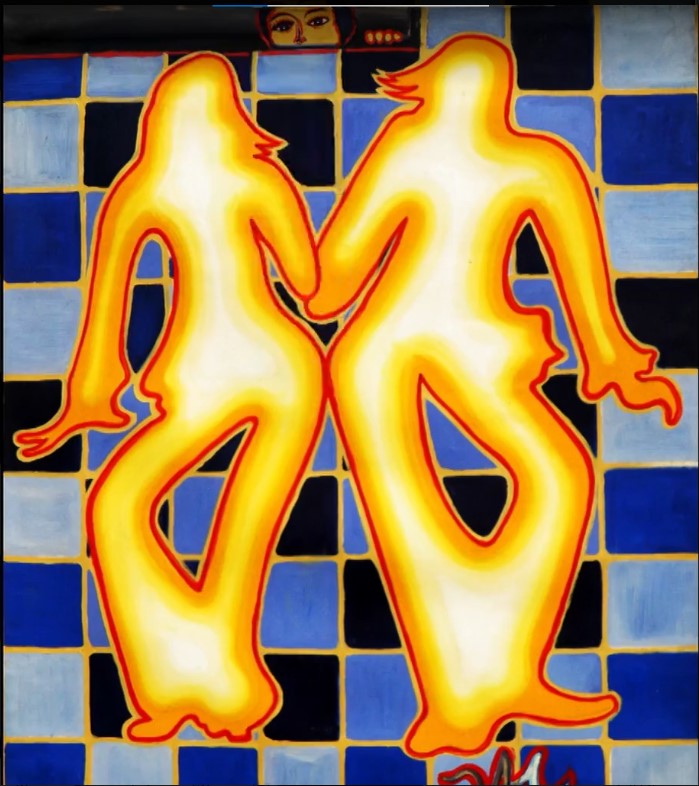

Boy with Disco – Yan Li

Cropped due to screenshotting

In the words of the artist of this piece, Yan Li: “I think I love disco because it demonstrates life. The rhythm, the power, and the enthusiasm” (Beijing Spring). The content of this piece of work really captures that rhythm, power, and enthusiasm. However, what is most curious isn’t the colors, which quickly captivate the viewer, but rather the individual at the top of the painting, peering in from a place which lacks such color, seemingly entranced as they intently watch the dancers. Once again, this work seems to associate cooler, darker colors with control or a shortfall of freedom. Moreover, this work in particular seems very inspired by western clothing as the dancers are seemingly wearing bell bottom jeans, which were very popular in the 1970s, especially in America.

Above all else, I believe that this work captures the feelings of curiosity that young people had during the Beijing Spring. The world suddenly appeared to be opening up to them. Many young people went to the street and danced to the sound of this new disco music, opening up a new kind of freedom previously unknown.

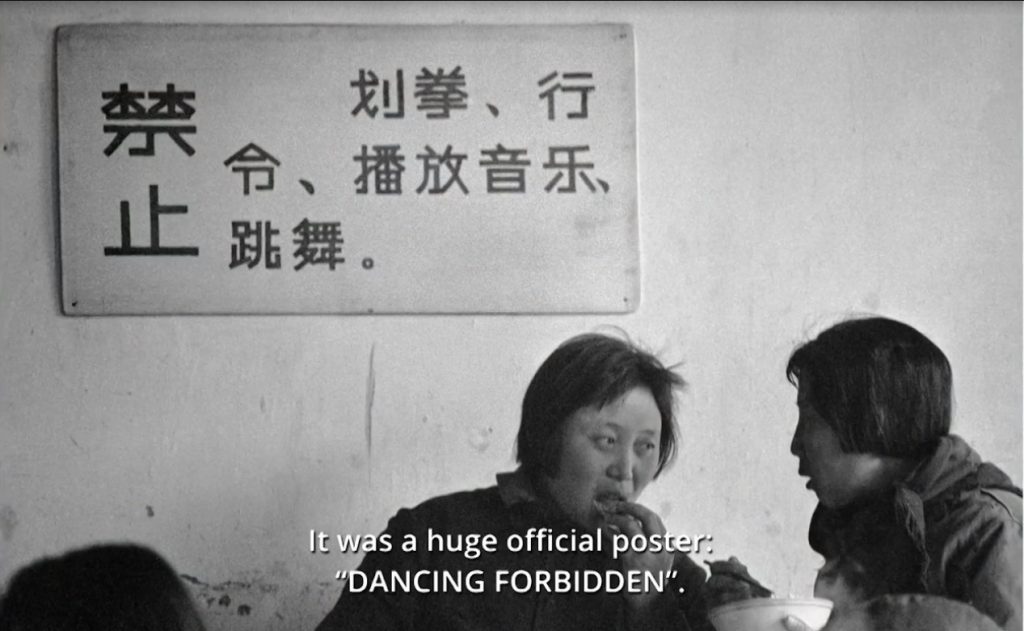

Cropped due to screenshotting

However, much like the previously held exhibition which was very informal (i.e., not sanctioned by any government body), dancing faced the same ban (Beijing Spring). However, with the spirit that the young people had created with their newfound freedoms, there was little that could be done to truly prevent them from pursuing it in the short term. Instead, it simply moved to their homes and private (Beijing Spring).

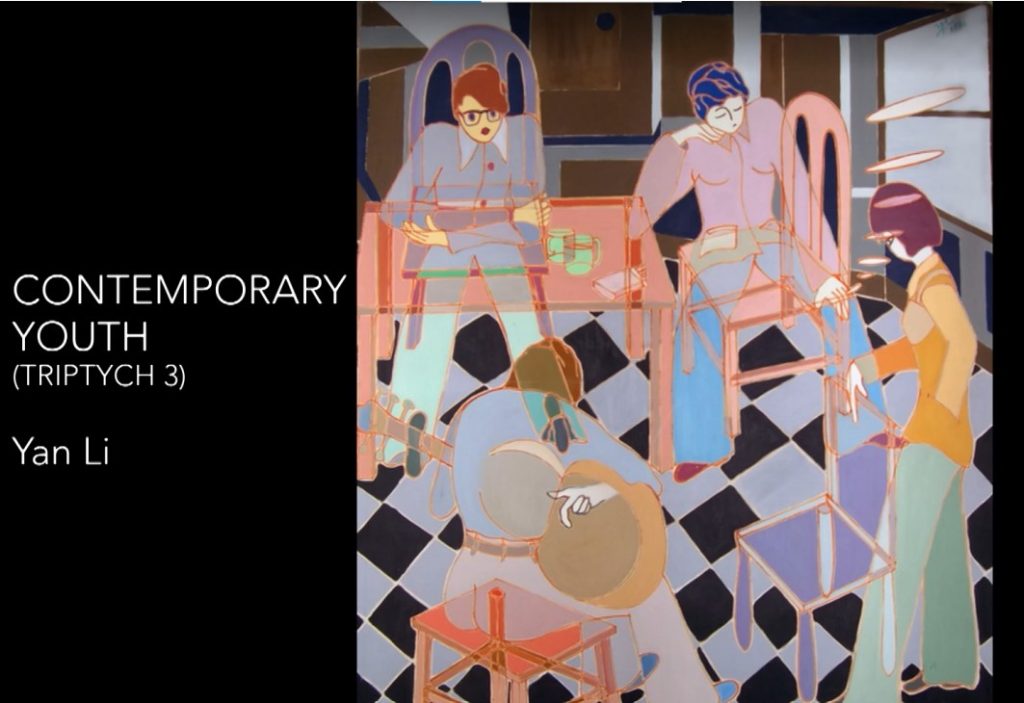

Contemporary Youth (Triptych 3) – Yan Li

Last of the pieces that will be explored is Contemporary Youth (Triptych 3) by Yan Li. This painting explored what the next steps were for the democracy-seeking youth. Instead of going out, they were instead, in their homes, where they could be less restrained. There were several pieces by Yan Li which explored this period of time. All had themes of vibrant color as in the piece shown above.

However, what is most striking to me is this work’s use of transparency. None of the objects or people in the room appear incredibly solid, unless contrasted with the background or the floor. This gives quite a feeling that we are not exploring a point-in-time within the room, but rather the fact that there is constant motion throughout the room. I believe this work displays the room and objects over a period of time, as sometimes we would observe the objects which are somewhat covered, and other times they would be completely visible. The objects in the room are not separated by distance, but rather by time. Furthermore, to continue the common theme of the use of color, the objects in the background that constrain the individuals tend to be darker, with colors such as brown and black, whereas the objects in the room are much more colorful. This once again could be a reference to how their freedoms and beliefs feel constrained by the world they live in. This is especially true when the faces and body positions of the individuals are considered. Despite the vibrant colors, the individuals look rather solemn. They are free, but only in a limited setting.

Ultimately, I believe this work is representative of the idea that the life of the youth was very vibrant but becoming more and more restrained. Yes, they had the freedoms to do as they wished in their homes, but how could they be sure this freedom wouldn’t be constrained in the future as well? Moreover, the pro-democracy movement was not immune to persecution, so the future did not look bright for these individuals (Beijing Spring). Soon after, there was an arrest and a sentencing, and it was clear to many members of the Stars that it was time to move on (Beijing Spring).

Conclusion

- Source: Beijing Spring Cropped due to screenshotting

- Source: Beijing Spring Cropped due to screenshotting

- Source: Beijing Spring Cropped due to screenshotting

- Source: Beijing Spring Cropped due to screenshotting

In all, four works have been explored. Two of which represent China’s political situation and upheaval and two which represent the mood of the people at the time of the Beijing Spring, particularly the Stars and other young people. When contrasting the two, something profound occurs. The works showcased outside the museum, which focused on themes of oppression and reconnection were much more solemn. However, the works that expressed the emotions and the excitement of the young people, their excitement for change, were much more vibrant. Nowhere else is this more evident than in the contrast of the use of color between these two sets of work. The first two contain much cooler colors, with emotion created through darker colors, namely black. In contrast, the works which express the younger people contain warmer colors, yellow, red, orange, and colors and figures that pop at the eye. This shows that while the people felt the weight of the situation they were in, they privately were quite optimistic and open, at least to some extent.

These works show how the movement for democracy in Beijing spring made the Stars and other pro-democracy individuals only showed individuals the unfortunate bounds of their freedom. First, it was shown how the people feel persecuted by a deafening darkness, unsure of how to act in Ma Desheng’s People’s Cry. Second, it was shown how these individuals were not free to remember the past, and how the banning of the exhibition ironically led to Huang Rui’s Old Summer Palace: Rebirth to suddenly become more meaningful in light of its restriction, as it was the people who had been turned to the same darkness in Ma Desheng’s People’s Cry. Next, the works post exhibition ban were explored, where it showed the curiosity of the individuals taking place in the Beijing Spring through Yan Li’s Boy with Disco. Lastly, it is ultimately discovered that the individuals are truly limited in their freedoms as shown in Yan Li’s Contemporary Youth (Triptych 3), which shows the colorful people, much like those who were dancing in Boy with Disco, sitting around, solemn about their apparent bounds.

The Beijing Spring seemed to fizzle out. Many of those who truly desired freedom no longer wished to remain in the country. However, the legacy of the Beijing Spring undoubtedly lives on in Beijing. The memories of those that participated or witnessed it will always be there. This is exemplified by the many protests that have happened in Beijing since then, such as the Tiananmen Square Protests which led to the 1989 massacre and the Sitong Bridge protests in October 2022. Moreover, the recent protests at Tsinghua University had students shout sayings such as “Democracy and the rule of law, freedom of expression” (AFP – Agence France Presse). This is very similar to the “Demand political democracy!” and “Demand artistic freedom!” shouted all the way back in 1979 (Beijing Spring). Beijing, while being the heart of the CCP, is also at the heart of the pro-democracy movement as well. It is here that the spirit of the Stars lives on.

Citations

AFP – Agence France Presse. “Hundreds Protest Covid Lockdowns at Beijing’s Tsinghua University: Witness.” Barron’s, 27 Nov. 2022, www.barrons.com/news/hundreds-protest-covid-lockdowns-at-beijing-s-tsinghua-university-witness-footage-01669533006. Accessed 4 Dec. 2022.

“Beijing Spring.” VOA News, directed by Andy Cohen and Gaylen Ross, Mar. 2021, www.voanews.com/a/beijing-spring/6797842.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2022.

Media Attributions

- People’s Cry © Ma Desheng

- Old Summer Palace: Rebirth © Huang Rui

- Boy with Disco © Yan Li

- Dancing Forbidden © Beijing Spring

- Contemporary Youth (Triptych 3) © Yan Li