Taipei

10 Analysis by Helen Ha

Helen Ha

Introduction

Museums are often considered to be authorities when it comes to providing objective and accurate historical depictions and information to the general public. In Taiwan, where tourism makes up a significant part of their economy, museums are a popular destination to learn more about Taiwan’s history and culture. However, as they are curated by humans with their own biases and perspectives, it is expected that certain details may be highlighted or diminished at the whim of the curator. I will go in depth about how museums and their authority on the facts they put forth influence ideas of national identities, explore the significance of the 228 Incident and explain how it played an integral part of Taiwanese identity, and show how that information is presented in the memorial museum. Lastly, I will be analyzing how Taipei’s historical and cultural values are shared through tourist attractions, specifically the 228 Peace Memorial Museum and how these values end up getting lost in translation when they try to cater to tourism and foreigners.

Museum Authority and Influence on Ideas of National Identities

First, I would like to point out how museums serve as an authoritative figure on national identity and are pivotal in visitors’ understanding of a nation and its history. As Fiona Mclean states, museums “are very much implicit in the social and political agendas of the 21st century. In particular, narrating the nation in the museum increasingly becomes a task of narrating the diversity of the nation and for engaging in a politics of recognition” (Mclean 1). From this, we begin to understand and see that museums can be very selective in what they educate the public about and will leave out certain aspects of history either to promote or follow the political affiliation of its founders or appease their gracious sponsors. For example, Mclean mentions how “the museum has had to address the questions of whose history is being constructed and whose memories are being negotiated by the museum, and ultimately whose voices will be heard and whose will be silenced,” showing how museums ultimately have the power to teach the public about history while also leaving some other aspects out such as diversity or non-hegemonic ideas (1). The general public often has the assumption that museums fully and accurately portray history and cultural artifacts completely and objectively without leaving anything out, but the decisions on what information the public receives is more complicated than we would expect. Not all museums are inclusive and represent the diversity reflective of people’s lived experiences.

228 Incident and Its Historical Importance

To highlight some issues with how information is presented in museums, I would like to talk about the 228 Incident and its historical meaning to Taiwanese people. On February 27, the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau received information regarding a shipment of illegal cigarettes being distributed and sold. While investigating businesses, they encountered a woman who was selling these illegal cigarettes and confiscated both her product and her earnings. As she held onto the officer’s leg, begging them to give back what was rightfully hers, she got beat up by a pistol, and this commotion brought a lot of attention toward them. Witnesses were outraged at this unfair treatment to this woman and, being overwhelmed by the swarm, one of the agents opened fire, which unfortunately ended up being fatal for a civilian. This resulted in many protests and unrest that lasted for three to four months. From February 28 to March 7, the Kuomintang viciously repressed locals. After March 7, reinforcements from the Mainland arrived, and these crackdowns became even more violent. Soldiers would fire upon innocent and unarmed people in order to instill fear in others with the hopes of restoring order. By the end of the month, it was estimated that thousands of people were killed by the Nationalist army (Shattuck). Some students who were even tricked into maintaining order during the rioting turned themselves in only to end up being imprisoned or executed. Taiwan, as a whole, was terrorized by the military and its government, and people began to vanish and were never heard from again. These massacres were then followed two years later by the capture, imprisonment, and torture of people which we now refer to as the White Terror. This was thirty-eight years of martial law, which lasted until the end of 1987. People were encouraged to turn against their family and friends to report and turn in “communist spies” in an effort to eradicate red power in Taiwan. Over 100,000 people were imprisoned, and over 1,000 were executed.

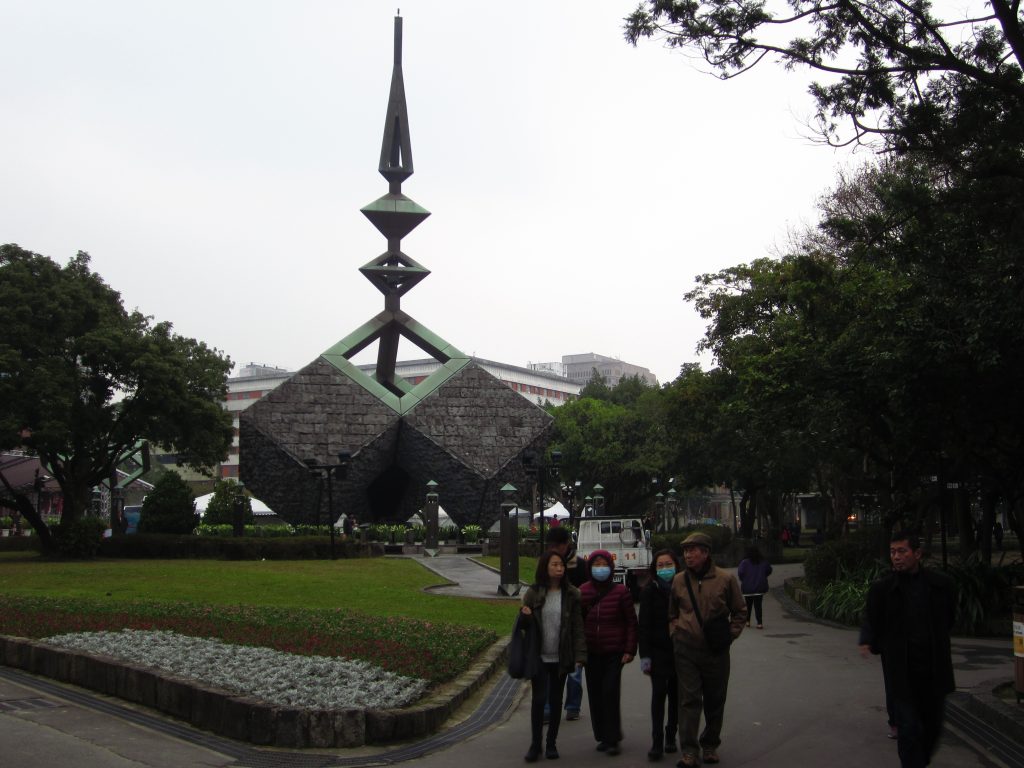

Depending on the person, the 228 Incident holds a different historical importance. For some, the date is just a day off and an accident that escalated to the extreme. For others, it is a reminder of the painful and sorrowful events that occurred over seventy years ago. But beyond the individual perception of the 228 Incident, the deeper significance of this event was that throughout this time period, the Taiwanese people were fighting for their national identity. They were tired of being controlled by the Japanese and Chinese. The scars of these tragic events are still felt throughout Taiwan today, but there are many things being done to rectify these past transgressions. President Lee Tung-hui officially apologized in 1995 for the government’s actions during the incident, and he began to push for an open discourse about Taiwan’s past (Shattuck). For something that was taboo and never spoken of for the longest time, the invitation to openly discuss Taiwan’s troubled past was a huge leap forward in healing Taiwanese people’s deep wounds. Additionally, to address the victim’s families that were impacted, the 228 Memorial Foundation provides them with compensation. They also maintain the documents related to the white terror. Today, just a few blocks away from the Presidential Palace in Taipei, the memories of the victims and the details of the event are preserved in the 228 Peace Memorial Park and museum. The museum is located at the very radio station that protesters stormed on February 28 to broadcast their rallying cries, and features a sculpture that honors the victims. The sculpture has a beautiful engraving that essentially states that in order to overcome serious tragedies in society, we must work together as a whole and we must work together to take care of each other and treat each other with compassion and sincerity to get rid of hatred and resentment and to bring about everlasting peace.

228 Peace Memorial Museum Lost in Translation

This memorial has a deep history rooted within it and as such, has great meaning to the locals. Therefore, it is unsurprising that tourists who want to know more about the incidents that took place will flock to this museum. However, due to the differences in language, sometimes, the meanings and significance of the events that transpired would end up being understated when presented to a foreign crowd. One example is how subtle nuances between the Chinese and English descriptions can completely change the context of the event being transcribed (Chen and Liao).

To reiterate, museums have great power when it comes to educating the public about nations and national identity (McLean). In this specific scenario, the museum is educating tourists about the tragic 288 Incident and its importance to Taiwan’s national identity. Because the museum is heavily expected to present information as accurately as possible about this occurrence, there is a lot of authority that comes with the information that this museum puts forth. However, in order to accommodate tourism, since it is the majority of Taiwan’s economy, there needs to be translations so foreigners will be able to also understand Taipei’s troubled history. When translated to English, the direct translations of the Chinese words are used, which often leads to the meaning of that event being lost. Chen and Liao give a nuanced example as to when direct word for word translation changes the context and meaning of the sentence.

“(ST) 此外,民眾也遷怒外省人,濫施報復。走避不及的外省民眾遭到圍毆,本省籍民眾則受到巡邏憲兵、軍隊的槍擊或毆打,全臺陷入大規模混亂狀態。

[Besides, the public took their anger out on wàishěngrén, and retaliated. Some wàishěngrén could not escape and were beaten by běnshěngrén. Běnshěngrén were shot or beaten by patrolling military police or troops. The entirety of Taiwan was in large-scale chaos.]

(TT) In addition, the public took their anger out on non-Taiwanese civilians, and retaliated. Some non-Taiwanese civilians were beaten by Taiwanese people; some Taiwanese people were shot or beaten by armed forces. Taiwan was in chaos” (Chen and Liao 62).

This passage describes a conflict between “wàishěngrén” and “běnshěngrén,” which respectively translates to “non-Taiwanese people” and “Taiwanese people” when translated to English in the museum information. The nuance that is lost in English is that these two terms have long been used to describe those who came to Taiwan during and after the Internal Civil War and those who came before Japanese colonization in 1895. However, Chen and Liao argue that the use of “Taiwanese” and “non-Taiwanese” is very open to more than one interpretation, given Taiwan’s current controversial political status. It has been contested that the meaning of the term “Taiwanese” has shifted from an ethnic term for “native Taiwanese” to a political term for “citizens of Taiwan.” Therefore, in the modern context, the difference between non-Taiwanese and Taiwanese typically does not refer to geographical boundaries but to political identity (Chen and Liao 62). Most foreign tourists would simply recognize any citizen of Taiwan as Taiwanese, rather than understanding those subtle nuances about “insiders” or “outsiders” that were significant to the Taiwanese people. In Chinese, the history and culture are captured in the words used to describe the people, but foreigners would be unable to recognize that significance due to potential limitations of the language. The identity of “Taiwanese” encompasses more meaning than a direct English translation can capture.

Conclusion

As Taiwan continues to navigate its complex political identity and the national identity that the Taiwanese people want to claim for themselves, tourism will continue to play a role in shaping that identity. Globalization is a major factor influencing cultures around the world, especially in Taiwan, where tourism is an important part of the economy. The information presented in museums is how foreign tourists understand Taiwan’s history and culture. By understanding what is being shown and how, Taiwan can influence how other foreign parties view their country, or at least teach foreigners what values they prioritize and their national identity.

Works Cited

Chen, Chia-Li, and Min-Hsiu Liao. “National Identity, International Visitors: Narration and Translation of the Taipei 228 Memorial Museum.” Museum and Society 15.1 (2017): 56-68.

Hsu, Sheng-chieh. “The Consciousness of the Taiwanese Identity and Museums in Taiwan.” (2006).

McLean, Fiona. “Museums and National Identity.” Museum and Society 3.1 (2005): 1-4.

TaiwanPlus News. “What Is 228? The Precursor to Taiwan’s White Terror Era | TaiwanPlus News.” Youtube, 25 Feb. 2022, youtu.be/Ph2XV4iHYeo.

Shattuck, Thomas J. “Taiwan’s White Terror: Remembering the 228 Incident.” Foreign Policy Research Institute, 27 Feb. 2017. www.fpri.org/article/2017/02/taiwans-white-terror-remembering-228-incident/.

Media Attributions

- 228 Monument © Ken Marshall is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 228 Memorial Park Pagodas © lienyuan lee is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license