Beijing

2 Economy/Culture/Religion

Peijun Zhao and Yesenia Bernal

Basics of China’s Economy in Three Videos:

Overview of Beijing’s Economy:

Agricultural Sector

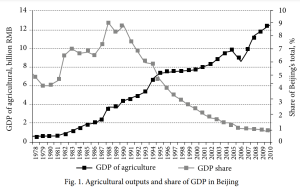

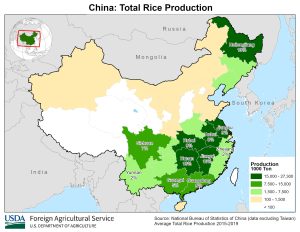

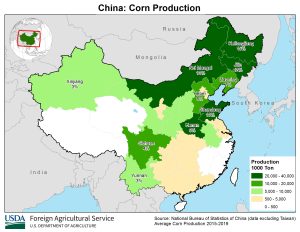

China’s economy originally started out largely agricultural before rapidly increasing in productive outputs after opening up to foreign trade and investments in 1979 (Morrison 1). To understand this, we can discuss Yang et al. (2012), which highlights the interdependence between the agricultural and urban sectors of Beijing between 1982 and 2007. Though Beijing’s large population requires a developing agricultural sector to feed its people, the economic output of agricultural products is consistently lower than technological investments. This is observed in Figure 1, where the share of GDP from agricultural goods sharply dropped after the 1900s (Yang et al., 629). As such, most of the primary crops consumed in Beijing, including rice and corn, are produced south of the city, primarily in Jiangsu and Shandong provinces.

Economic Output

As a city, Beijing has one of the highest PPP-adjusted GDPs in the world and is prophesied to have the 5th highest GDP in the world by 2025 (Dobbs et al. 3). For reference, GDP is defined as the “gross domestic product,” or the total monetary value of goods and services produced in a specific area. As different countries have different purchasing power, the monetary wealth of a country should be adjusted according to the purchasing power of the currency in that country. Consequently, Beijing places 9th in China with a PPP-adjusted GDP of 950.671 (Jacobs 1). As these values are varied based on the country and economic output, the GDP ranking of Beijing may rise to 8th place next year, while Moscow (rank 8) may shrink due to decreasing manpower and economic production from the events of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Notably, Shanghai’s PPP-adjusted GDP is ranked 7, which is the highest in China, and has a PPP-GDP output of 1,018.815 (Jacobs 1). Overall, China’s total PPP-adjusted GDP is 27,206.09 billion, and Beijing accounts for 3.5% of China’s total GDP (Zhou 1).

To understand why Beijing’s economic output is integral to China’s economy, it is important to identify the main sectors that account for Beijing’s economy. The first sector regards the real estate and housing district. Beijing is home to 145 of the top 500 companies in the world, slightly surpassing the United States’ 124 top companies (Flannery 1). The United States capitalizes in the defense, airline, tech, retail, entertainment, healthcare, and wholesale industries. In comparison, China’s main sectors focus on chemical, energy, engineering, transportation, and commercialized banking (Harper 2). These companies include the State Grid Corporation of China, Sinopec, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Sinochem, China Life Insurance Company, the Bank of China, and China Mobile (Flannery 2). Furthermore, China’s top two universities, Tsinghua University and Peking University, make Beijing a top destination for both students and industries wishing to grow. However, it is notable that these companies gear their investments internally through China and do not have sufficient international Western investments (Zhou 1). Based on these assessments, it is understandable that Beijing’s real estate and automobile sectors are also valuable due to the need for highly paid workers and exceptional students wishing to enter the workforce.

Another notable sector of Beijing’s economy includes the Central Business District, which encompasses the location for many of the Top 500 Fortunes to set headquarters and access well-established city planning, media coverage, and cooperation among high corporate profiles (Yang 1). This diverse set of investments results in Beijing having one of the world’s highest GDPs.

Works Cited

“China – Crop Production Maps.” USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 2019, https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/rssiws/al/che_cropprod.aspx.

Dobbs, Richard, et al. Urban World: Mapping the Economic Power of Cities. Mar. 2011, www.mckinsey.com/mgi.

Flannery, Russel. “China’s 100 Richest 2022.” Forbes, 9 Nov. 2022, https://www.forbes.com/lists/china-billionaires/?sh=4750d15b2d43.

Harper, Justin. “Beijing Now Has More Billionaires than Any City.” BBC News, 8 Apr. 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56671638.

Jacobs, Frank. “These 1,000 Hexagons Show How Global Wealth Is Distributed – Big Think.” BigThink, 10 June 2021, https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/gdp-map/.

Morrison, Wayne. “China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States.” EveryCRSReport, 25 June 2019, pp. 1–25, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RL33534.html.

Stubblefield, Nick. The Economy of Communist China. YouTube, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YtzFn73sYmU&list=PLh6oq2EbSNEcdFicY7wr9va_bym8mzGTM&index.

Stubblefield, Nick. The Economy of Modern China. YouTube, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNhsB0h7gZc&list=PLh6oq2EbSNEcdFicY7wr9va_bym8mzGTM&index.

Stubblefield, Nick. The Historic Economy of China. YouTube, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vi-U9wfa3CE&list=PLh6oq2EbSNEcdFicY7wr9va_bym8mzGTM.

Yang, Chao. “Central Business District.” China Beijing, 2022, https://english.bjchy.gov.cn/central-business-district.

Yang, Zhenshan, et al. “Rethinking of the Relationship between Agriculture and the ‘Urban’ Economy in Beijing: An Input-Output Approach.” Technological and Economic Development of Economy, vol. 20, no. 4, Taylor and Francis Ltd., Jan. 2014, pp. 624–47, doi:10.3846/20294913.2014.871661.

Zhou, Qian. “Decoding China’s 2021 GDP Growth Rate: A Look at Regional Numbers.” China Briefing, 7 Feb. 2022, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-2021-gdp-performance-a-look-at-major-provinces-and-cities/.

Culture and Religion

The capital of China has long stood the test of time, long before the start of the first century. Throughout the centuries, Beijing has collectively created its own culture that is rich and diverse in multiple ways. The capital has developed its form of language, food, religion, and unique festivals. In this case, the main focus will be on a brief overview of some of Beijing’s culture with some background information on its aspects.

Language

Mandarin Chinese is known to be the most widely spoken language in the world. The history of the language came from being a Beijing dialect. Initially, historians and researchers noted the language of Mandarin to come from as early as the Yuan Dynasty. Following the Yuan Dynasty, the Ming Dynasty began using a Nanjing dialect when Nanjing was the capital. However, the Beijing dialect became the secondary official tongue after the Ming Dynasty changed the capital from Nanjing to Beijing. At the start of the Qing Dynasty, the Beijing dialect was declared the official tongue. About halfway through the Qing Dynasty, Emperor Yongzheng proclaimed the Beijing dialect to be the official spoken Chinese language for official affairs (Guo 220). Towards the later years of the Qing Dynasty, officeholders were just some of the people speaking the Beijing dialect. The dynasty tried to declare the dialect as the common tongue during this time.

Notwithstanding the end of the Qing Dynasty, there was still a debate about whether the Beijing dialect should be officialized as the common tongue. At this point, Beijing remained the Republic of China’s capital and became more popular than the other dialects. Towards the end of the Republic of China era, an agreement was created to officialize the Beijing dialect as the national tongue in 1924 (Guo 220). More than thirty years later, the National Language Reform Conference voted for the Beijing dialect to remain the national tongue, renaming it Putonghua, also known as the Common Tongue (Guo 220).

Although the Beijing dialect went through several tries to become the common tongue, the dialect did not stop changing and modifying. Mandarin can be categorized into three subgroups spread throughout central, northern, and western China (Chai 99-100). Even the subgroups have different tones and grammar structures. The different tones and grammar structures help identify the difference between Cantonese, Shanghainese, and other similar languages spoken in Beijing.

Food

Part of Beijing’s culture is made up of the food popularized in the capital and has spread throughout the world. One of those dishes is the Peking Roast Duck. The Peking Roast Duck is known for its tedious preparation and crispiness. The preparation begins with force-feeding a specific duck breed for about six months. Once the duck is ready for cooking, it is slaughtered, plucked, and cleaned. Air is then puffed through the neck so that the flesh and skin are loosened from one another. Afterward, the duck is smeared with water, honey, and vinegar mixture and set to dry for three days. After the three days have passed, the duck is grilled in a special oven while still hanging. The duck is served with side dishes, such as hai xian sauce, sesame-seed rolls, sweet bean sauce, spring onions, and thin-like pancakes (Insight Guides 196-198).

Another dish that has become popularized in Beijing is the Instant-Boiled Mutton. The original cuisine has to be prepared carefully and precisely with particular ingredients. The broth is made with chopped green onion, dry shrimp, mushrooms, and ginger in a pure copper pot heated by charcoal. The ideal mutton pieces come from the fore shank, back neck, and hind shank. These pieces are then cut to approximately 0.9 millimeters thick, 13 centimeters long, and 3.3 centimeters wide (Guo 222). Once the mutton is cut and ready to cook, it is dipped in the boiling broth for a few seconds and then dipped in the sauce of choice. The sauce used as a dip for the mutton pieces is a mixture of fermented shrimp sauce, Chinese leek flower, chopped cilantro, fermented bean curd, and ginger. Hot chili oil is another side sauce that can be used for mutton. Other dishes accompanying the mutton include tofu, sesame biscuits, napa cabbage, buckwheat noodles, and mung bean vermicelli. The meal ends with leftover enriched broth and sweet pickled garlic.

Although other main dishes are part of Beijing’s culture, the other part of its cuisine is street food, also known as “Beijing tapas.” According to Guo, “Beijing tapas are small portions of a great variety of delicacies that can be enjoyed as appetizers or snacks or as a complete meal when an adequate amount is consumed” (223). Some street foods include jian bing, xian bing, or meat skewers. More street foods are offered in Beijing for an affordable price throughout the capital.

Religion

Beijing has come a long way with its religious affiliation. In 1949, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) declared itself to be atheist, as well as for its members (Chai 281). Nonetheless, the country has officially recognized five other religions: Islam, Catholicism, Daoism, Protestant Christianity, and Buddhism. Confucianism started becoming popular again after the Cultural Revolution halted this religious practice (Insight Guides 162). The citizens can practice these different religions as long as the members are integrated into a state-sanctioned temple or church. However, other religions have not been recognized by the constitution and can also be known as “underground churches.” The members of these underground churches usually meet in people’s living spaces for services.

Festivals

Beijing celebrates national and local festivals and holidays throughout the year. One of the local events that Beijing celebrates is the Beijing International Music Festival. The Beijing International Music Festival was established in 2004 and is celebrated every year in October. The event sponsor, the Beijing International Music Festival and Academy, allows students, artists, and faculty members to perform and present their musical talents. Additionally, students participating in the event can compete in the Concerto Competition and potentially win an award at the Gala Finale Concert (Quan 2021).

Another festival that is popular in Beijing is the Yuyuantan Cherry Blossom Festival. The festival is celebrated yearly during the springtime, between March and May. More than thirty species available at the park make up more than two thousand cherry trees. The cherry trees were initially received as a gift from Japan in the 1970s when both countries reinstated their diplomatic ties (“Best Time,” n.d.). Although the two countries reinstated their diplomatic ties in the seventies, it would take more than a decade before the first festival was celebrated in 1989 (“Tips on Yuyuantan,” n.d.).

Recap

Although many more cultural factors make Beijing, these elements offer a glimpse of what makes up the capital. To better understand Beijing’s culture, consider making a trip to the capital in the near future to have a first-hand experience.

Works Cited

“Best Time to See the Cherry Blossoms in Beijing « China Travel Tips – Tour-beijing.com.” Tour-beijing.com, https://www.tour-beijing.com/blog/beijing-travel/best-time-to-see-the-cherry-blossoms-in-beijing. Accessed 5 Dec. 2022.

Chai, May-Lee, and Winberg Chai. China A to Z: Everything You Need to Know to Understand Chinese Customs and Culture. Plume, 2014.

“Enjoy Beijing’s modernity.” YouTube, uploaded by China Culture, 07 June 2021, https://youtu.be/DTgMVjRN6_4.

Guo, Qian. Beijing: Geography, History, and Culture. ABC-CLIO, 2020.

Insight Guides. Insight Guides City Guide Beijing. 8th ed., Insight Guides, 2017.

Quan, Chris. “Beijing International Music Festival, Beijing Festivals.” Chinahighlights.com, China Highlights, 19 Oct. 2021, https://www.chinahighlights.com/festivals/beijing-international-music-festival.htm.

“Religions in Beijing 1900-2020 | Beijing Diversities |.” YouTube, uploaded by InfoXpace Q, 28 May 2020, https://youtu.be/1HASZpb7MlM.

“Tips on Yuyuantan Cherry Blossom Festival in Beijing.” Topchinatravel.com, https://www.topchinatravel.com/beijing/tips-on-yuyuantan-cherry-blossom-festival-in-beijing.htm. Accessed 5 Dec. 2022.

Media Attributions

- © Zhenshan Yang is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- China Rice Production Map © USDA Foreign Agricultural Services is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- China Corn Production Map © USDA Foreign Agricultural Service is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Henry Chen Beijing © Henry Chen is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license