5 Some Thoughts about Mimbres Pottery and Mortuary Customs

Harry J. Shafer

https://doi.org/10.52713/KWTQ9486

Introduction

I want to express my appreciation to Dr. James Farmer for inviting me to participate in this book honoring the legacy of my friend and colleague Dr. Terry Grieder. My initial connection with Terry began in the late 1960s. I first met Terry while working for UT Texas Archaeological Salvage Project, the agency conducting archaeological recovery in reservoir basins across the state. Terry was tasked with recording and interpreting some rock art murals in the Lower Pecos region as part of the Amistad Reservoir archaeological recovery program (Grieder 1965: 1966). Later in that decade I took his art history course at UT-Austin. I was conducting archaeological projects and going to school part time. Being somewhat older than the mean age of the class, I had no hesitation to question Dr. Grieder in class since we took different approaches to the interpretation of prehistoric art, he from an art history perspective and me from an anthropological perspective, much to the surprise of the art students. In addition to his interest in ancient rock art imagery, Terry also maintained a strong commitment to the importance of ancient ceramic arts, especially pottery, in the interpretation of ancient societies (see Koontz and Farmer, this volume).

In 1984 the Witte Museum in San Antonio organized a “think tank” to bring together a select group of scholars to discuss hunters and gatherers across the world in preparation for a new gallery. The purpose of this gathering was to generate content and a book for a permanent exhibit entitled Ancient Texans. The exhibit featured comparative hunter-gatherer cultures from the Lower Pecos Region of Texas to South Africa and Australia. Terry and I were among the scholars who were invited to that gathering. One product of that think-tank was a book I edited, Ancient Texans: Rock Art and Lifeways of the Lower Pecos (Shafer 1986), that included a contribution by Terry entitled “Recording and Interpreting Lower Pecos Pictographs: Methods and Problems” (Grieder 1986: 176-179).

The ancient Mimbres culture in southwestern New Mexico is best known in the art and archaeology worlds for their exquisitely painted black-on-white pottery (Brody 2004). The Mimbres culture, a regional Mogollon tradition centered in southwestern New Mexico along the Mimbres River, began about 200 CE and culminated during the Classic Period, 1010-1130 CE (Hegmon et al., 1999). Mimbres ruins occur eastward to the Rio Grande Valley, to the upper Gila River Valley, and southward into northern Chihuahua, Mexico. The ruins, unlike those in Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, and elsewhere in the Four Corners area, are unimpressive. They were constructed of cobble-adobe masonry that melted into piles of rubble over time. It is the painted pottery, however, that has drawn archaeological and art-historical attention to the Mimbres culture.

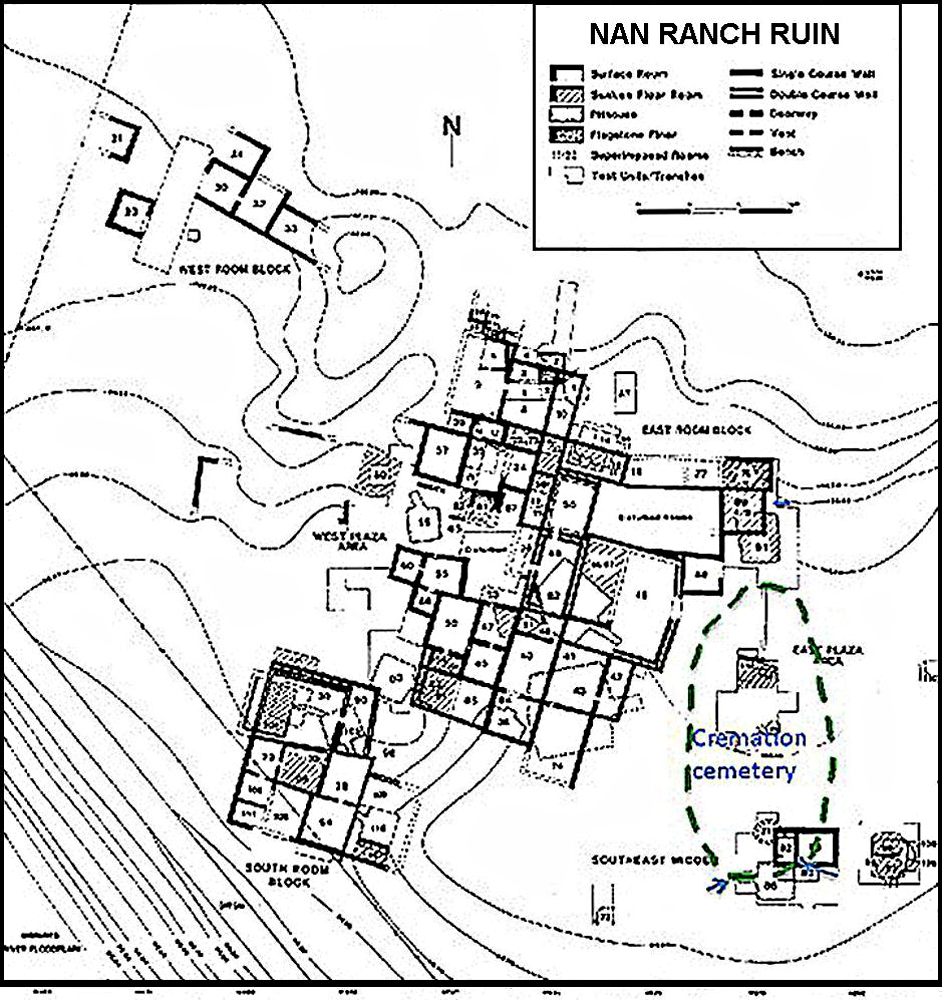

From Shafer 2003: Figure P:2.

The ceramic and mortuary data used in this chapter comes from my excavations at the NAN Ranch ruin in Grant County, New Mexico.1 The ruin was excavated by a team from Texas A&M University under my direction from 1978-1996 (Figure 5.1) (Shafer 2003). The site consists of at least four Classic Mimbres room blocks overlying part of a large pithouse village that dates from throughout the Late Pithouse Period. The investigation exposed most of two room blocks, tested two others, explored outdoor space, and recovered an enormous amount of material culture and data, including a large collection of ceramics that are now accessioned at the Western New Mexico University museum in Grant County.

Mimbres Pottery

The exquisitely painted Mimbres pottery is a white-slipped brownware. It is technologically made of generally poor-quality clays using the coil-and-scrape method of production. Use of white slip as a canvas on the brownware begins sometime in the Late Three-Circle phase, c.850 CE. Firing was probably in above-ground kilns and reduced firing to achieve the black-on-white was not well controlled. Some vessels were accidentally, or purposely, oxidized to a red-on-white and some were partially oxidized. As a ceramic tradition the basic technology remained consistent, but the decorative styles changed over time with subtle micro-stylistic changes occurring about every generation or so (Shafer and Brewington 1995).

As Koontz and Farmer noted in Chapter 1, Terence Grieder emphasized the cross-cultural communicative function of meaning vs. function of style. This notion plays big in Mimbres ceramics given the rather dramatic stylistic change that occurred c.950-1000 CE and the proliferation of decorative ceramics after that date. In this chapter I address the stylistic progression of Mimbres painted pottery and the functional roles it served. While the main functions of the pottery were for cooking, serving, and storage, I go beyond those functions and show how the pottery was used in the ritual transformation from life to death.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer / Western New Mexico University Museum.

The three major styles are labeled Style I, Style II (both previously lumped under the heading of Boldface), and Style III (previously referred to as Classic Mimbres black-on-white) (Figure 5.2). Style I is distinguished by bold lines with wavy cross-hatched patterns. Style II is identified by geometric and naturalistic motifs outlined with bold lines with fine-line cross-hatching. In Style III, hatched motifs are all fine line. Micro-styles within Style II and III have been defined based on archaeological stratigraphy at the NAN Ranch ruin and have been a useful tool for ceramic cross-dating (Gilman and LeBLanc 2019; Shafer and Brewington 1995).

Most of the Mimbres pottery vessels viewed in museums and elsewhere were produced during the Classic Period (c.1010 to 1130 CE; Gilman et al. 2014: 93). Recent NAA studies have shown that most of the pottery was produced in the upper elevations of the Mimbres region by a limited number of cottage-level craft specialists (Creel and Speakman 2018). Curiously, many of the vessels seen in museums and collections have a hole in the bottom. The common interpretation for this attribute is a “kill hole” to deliberately render the vessel useless once it is placed in mortuary context (Brody 2004: 50). The kill hole was not due to people using pickaxes to excavate the sites as some might think but was a purposeful act of transformation by the Mimbres people as part of the mortuary ritual. In this paper, I discuss the varied mortuary behaviors of the Mimbres, and explain why many of the bowls were “killed” prior to being placed over the face of the deceased. It is imperative to review the variability in Mimbres mortuary behavior in order to provide a context and possible understanding of the purpose of the kill hole.

Mimbres Mortuary Practices

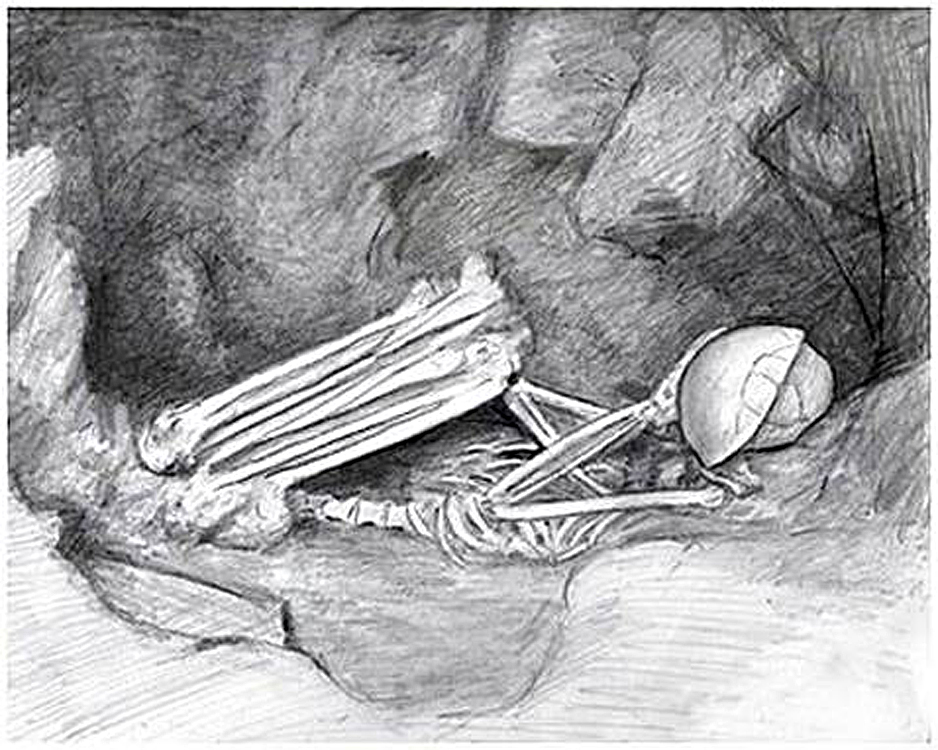

Illustration by Frank A. Weir.

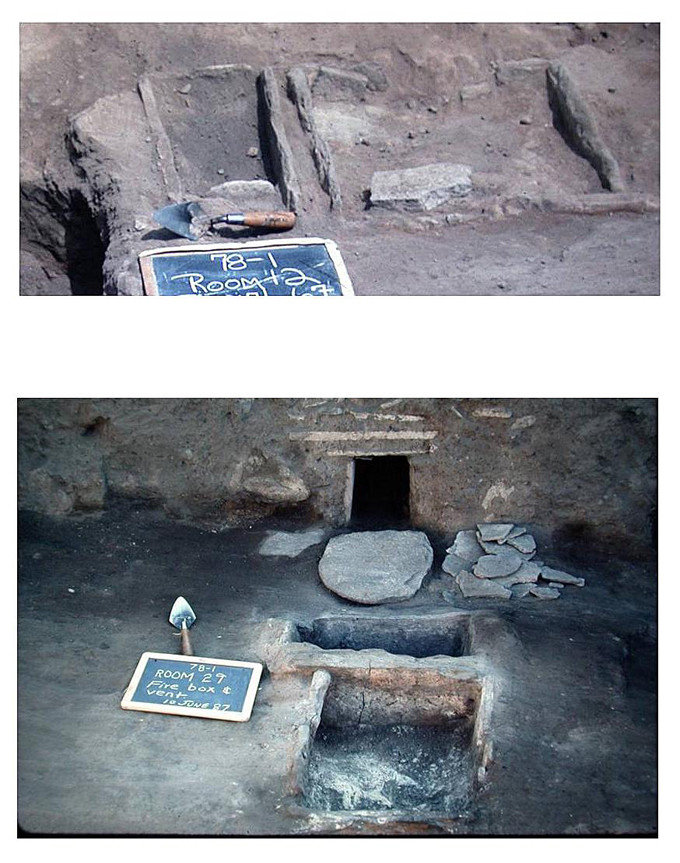

Photo courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer / Western New Mexico University Museum.

A great percentage of Mimbres bowls in museums were recovered from mortuary contexts, but this was not the primary function of the vessels, as noted above. They were made to be used in everyday functions, such as cooking, serving, and storage, as shown by the use-wear exhibited on the interior of the bowls (Lyle 1996). The most common reference to Mimbres mortuary practices was intramural burial beneath the floors with a “killed” bowl placed over or about the head (Figure 5.3) (Cosgrove and Cosgrove 1932: 23-29). But this was only one method of mortuary treatment, albeit the most common during the Classic Mimbres Period (1010-1130 CE) as about 55% of all burials at NAN Ranch ruin were associated with a mortuary vessel. Inhumation burials were flexed on the back with minor examples of flexed on the left or right, or sitting. There is some evidence that some of the burials were wrapped in shrouds (Figure 5.4). Extramural inhumations were more frequent during the pithouse period and cremations were infrequent but did occur. The trends toward intramural burial and cremation occurred in the Late Pithouse transition (c.950-1030 CE) albeit a few subfloor burials occurred prior to that time. The best example for indoor burials in the South Room Block location was in Room 104 with 13 interments including men, women, and children. This trend became commonplace in corporate households by the early Classic Period. Some were buried outside of structures in plazas and middens, and at least at the NAN Ranch a significant segment of the population was being cremated. Cremations were in specially-defined plaza locations, but cremating the dead ceased for all practical purposes by the mid-Classic Period. The question is what precipitated the change to indoor burial? Sophia Petrovich (2001) analyzed the NAN Ranch ruin mortuary data to assess the religious determinants of the spatial aspects. She examined the burial data with 36 cosmological themes based on cross-cultural studies of Native American Indian groups in the Southwest and northern Mexico. Petrovich offers an explanation for intramural burial:

In religious terms, the highly charged symbolic act of burying the dead with the living ensures that the ancestors of the living remain intimately conjoined to the descendents (sic). The Power of the ancestors would not be lost but would instead remain concentrated around the descendents (sic). In turn, the living could protect and propitiate the dead by protecting their remains from outside discretion. Such direct harnessing of the power of the dead is consistent both with the pan-Southwestern theme of Rain Beings associated with the dead who provide rain and other blessings and with the theme that the dead can return. After all, they never left (2001: 48).

Creel and Anyon (2003) and I (Shafer 2006) have speculated that the incorporation of irrigation agriculture was correlated with the move from pit houses to pueblos. I also think this architectural change is attributable, at least in part, to the mortuary change as well, and here is why. Domestic burial may have been related to the chain of inheritance and control of resources, particularly agricultural land. This pattern of indoor burial and inheritance of resources is well documented in Mesoamerica among the Maya (McAnany 1995: 65; Scherer: 2015: 174-177) where domestic burial was commonplace. Furthermore, as McAnany (1995: 16) argues, placing the dead within the domestic arena legitimized resource rights through lineal descent. I have mentioned elsewhere (Shafer 2006) that the indoor cemeteries restrict access to the dead whose spirits communicated to the descendants via the portal of the floor vault. These ancestors were guarded from public access due to competition between lineages for power within the community.

Elizabeth Ham (1987) was the first to investigate the social organization of the NAN Ranch ruin community. She examined all of the burial data through the 1987 season. She used the NAN burial data to see if there was any evidence for social ranking or distinction between the East Room Block and South Room Block populations. Like Anyon and LeBlanc (1984) and Gilman’s (2006) conclusion for the Galaz and Mattocks sites respectively, she did not find any marked evidence of social differences in the mortuary behavior that would indicate anything other than an egalitarian social organization. She noted, however, that females were interred with more ceramics than males, and that 38.46% of all females were interred with a pelvis/spine direction to the east. Ham attributes these statistically significant differences to the Mimbres society being matrilineal.

Diane Young Holliday (1996) offers another attempt to define social differentiation using osteological data. She posed the question: could the south room block women represent the prime lineage of the NAN population? As suggested by the “corporate-base strategy” towards complexity, perhaps emphasis was placed on the groups as a whole, and status was not expressed in the great accumulation of personal wealth”. She, like Ham, noted that more women had multiple vessels associated with them than the East Room Block. She found that South Room Block children were less affected by anemia than those in the East Room Block. Also, she noted that tooth loss in older women was greater in the South Room Block, possibly owing to their longer life span.

While studies of mortuary association and diet have not yielded apparent evidence for social differences within the NAN Ranch ruin Classic Mimbres Period population, location and energy expenditure in act of burial indicates some rather strong evidence for social distinction. The mortuary population of the South Room Block has already been shown to be much greater than if this suite was occupied by four or five families over several generations. Creel (2006) and Creel and Anyon (2003), have noted that placement of burial itself carries social distinction. This view follows Arthur Saxe (1970) that one should look for regularities in the process rather than in the formal attributes of the practices themselves. Therefore, the inordinate number of burials in the South Room Block compared to the East Room Block does indicate that the South Room Block carried an important place for burial in the community. The other notable cemetery location was the cremation area in the East Plaza. Cremations require much more energy expenditure in burial preparation than pit burials and are public spectacles rather than private ceremonies when compared to intramural interments as shown by the primary cremation at the NAN Ranch ruin (Creel 1989). I think the processes implied by both of these factors, location and treatment, when weighed together and compared to the other household suites described here quite clearly signify significant social differences among the lineages residing at the site.

The “Killed” Bowl

Mimbres mortuary bowls placed with inhumations were intentionally “killed” usually by perforating near the bottom. The perforations were usually done by puncturing the bowl with a pointed stone from the exterior (Figure 5.5) or interior (Figure 5.6), drilled (Figure 5.7:a), or smashed (Figures 5.8 and 5.9). Sometimes the attempt to kill the bowl resulted in breaking it; in such cases the fragments were assembled and placed over the head. There is evidence that the act of punching or “knocking” the hole occurred at the grave site. Instances where the kill hole was placed at the feet in the grave occurred at the NAN Ranch site. Also, as a cautionary note, there are at least three instances at the NAN Ranch site where additional holes were made in the vessels by digging sticks penetrating existing graves while attempting to dig new graves. These holes were off-center from the intentionally made “kill” holes.

Left: Mimbres Style III

Right: Mimbres Style II.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer / Western New Mexico University Museum.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer / Western New Mexico University Museum.

Left: drilled

Right: inside-out with fractured bowl and missing sherd.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer/Western New Mexico University Museum.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer/Western New Mexico University Museum.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer / Western New Mexico University Museum.

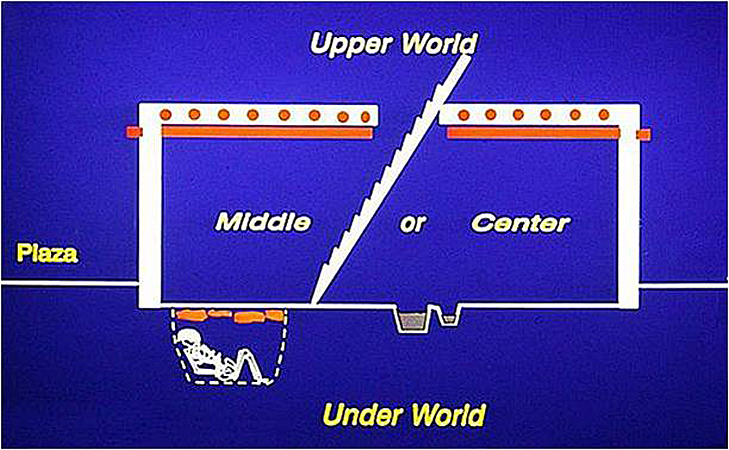

The common explanation for the “killing” of the bowl by puncturing or drilling a hole in the bottom was to release the spirit for the journey to the afterworld (see Burt 2013; Ellis 1968: 67). Granted the animistic beliefs of Native American Indians customarily attributed things in nature as has having souls. However, the behavior of placing a killed bowl over the face of the deceased possibly carries more complex implications. Barbara Moulard (1981: xviii) was the first to suggest that the bowl itself was symbolic of the earth sky dome placing the body in the Underworld. She also regards the “kill hole” as analogous to the sipa’pu, the connection between the Underworld and the corporeal world (Ibid). I have argued that while the metaphoric explanation of the layered universe may be correct, extending that metaphor to the built environment and the architecture within which the burial took place was also a recreation of the universe (Figure 5.10) (Shafer 2003: 212). I also posited that the bowl itself served as a mask and suggested placement of the mask transformed the once living being into an ancestral spirit.

After Shafer, 2003: Figure 12.1, credit Jason Barrett for color rendering.

I believe the kill hole provided a mouth for the mask that allowed the breath of the person’s spirit to leave and communicate ritual knowledge with the living. The ancestor’s spirit, who dwelled within the lineage household, provided the justification for the living to claim ancestral rights to the critical resources connected to that household, namely agricultural fields (Creel and Anyon 2003; Rice 2016: 141; Shafer 2006). Placement of the burials beneath the floor within the residential suite, out of the public arena, provided restricted access to the ancestral knowledge within the competitive social environment.

Another possible explanation for the kill hole in the mask is to allow the spirit person to breathe (McGuire 2001: 13). McGuire goes on to add in the Hopi case that the father or other male relative blackens the chin and places a “white-cloud mask” of raw cotton over the face” (ibid.; see also Moulard 1981: xxviii). The Hopi parallels are interesting, as are those of the Hohokam for the cremations. These ancient beliefs were probably wide-spread and shared among the Native American lineages and clans of Mesoamerica and the American Southwest.

Masking the dead was widely practiced in Mesoamerica (Headrick 1998), and perforating a bowl and then placing it over the face of the dead was also practiced by the Maya (Scherer 2015: Pl. 12). Vessels associated with most cremations were not perforated, they were smashed. The exceptions were urn cremations where the cremated remains were placed in pottery vessels. Most sherd concentrations marking cremation deposits were from vessels included in the funeral pyre, as they show evidence of burning. The smashing varied from breaking the vessel into a few sherds as in NAN Ranch ruin Feature 11-25 or, in one case, Feature 11-31, a single bowl was smashed to over 700 sherds (Shafer and Judkins 1996). The act of vessel “killing,” however, may also mimic the Hohokam pattern of breaking or smashing vessels with the belief they would be restored to completeness in the spirit world (Rice. 2016: 49). According to Rice (2016: 49), the greater the degree of smashing in this world, the more beautiful the restoration in the next. Interestingly, Rice cites the Pee Posh with the belief that reversal occurs in the Underworld. The logic being that property, including pots, is broken before entering the Underworld so they will be restored there. This belief of reversal is analogous to the Huichol belief that when one enters the sacred land of Wirikuta (the desert where the world was created), where peyote is gathered, behavioral reversals occur and are restored when one ritually leaves Wirikuta (Myerhoff 1974: 147-172). Interestingly, Bartlett (2013: 17-19) applies this notion of inversion, analogous to reversal, to the bowl placed over the head of the deceased in the Mimbres case.

The destruction of property at death is widespread among Native American Indians from Archaic times on, and is not limited to the American Southwest (Bartlett 2013). Smashing pottery vessels occurred in the Late Pithouse Period in the NAN Ranch sample. However, placing the bowl over the head or face as a mask represented a major change in the mortuary behavior during the Pithouse-Pueblo transition about 950-1000 CE.

Killed Vessels and Wealth or Prestige

Was the placement of a killed vessel indicative of the person’s wealth or prestige? If wealth in the sense of power and prestige and not material possession was expressed in any way within this Mimbres community, I think it was through legitimizing lineage rights to ancestral lands and resources, especially the irrigated fields that yielded bountiful food for the lineage members and their reciprocal agents. Were the people who held lineage rights to ancestral lands marked by being buried with bowl masks over the face or head? There is no age distinction between those with and those without mortuary a mask; ages ranged from infants to older adults of both sexes. That is the same age range for burials without mortuary association. Furthermore, at the NAN Ranch ruin only Classic Mimbres phase burials within rooms had killed bowls. None of the extramural burials had ceramics associated. Given that discrepancy, it would appear that killed bowls did have significant symbolism with regard to who had legitimate lineage rights and those who did not.

Archaeologists often regard “wealth” as measured by the number of items associated with any given burial (Gilman 2006). It is interesting that the wealthiest burials, as measured by associated items, were the children. This was true at the NAN Ranch ruin in the South Room Block rooms 28 and 29, and in the Room 47 suite with Burials 33 and 34. Infants or small children in Room 28 (Burial 128) and Room 29 (Burial 133) also had jewelry and multiple vessels associated (Parks-Barrett 2001: 216). Also, a burial excavated by Harriet and C. B. Cosgrove at the NAN Ranch site in 1927 (Cosgrove and Cosgrove 1932: 67; Pl. 76), possibly from the East Room Block, appears to have been the wealthiest interment at the site in terms of associated jewelry. Archaeologists often seek out the graves with the most material possessions as being the higher ranks to identify social stratification. Gilman and LeBlanc (2017: 267) have shown that is not the case at Mattocks where little evidence of social stratification was detectable through mortuary associations. This also was Ham’s (1989) conclusion after studying mortuary associations at the NAN. So why are infants and children getting the attention? Children may have been the rebirth of ancestors and were so venerated (Scherer 2015: 173), and Ellis (1968) mentions a Pueblo Indian informant stating that children were buried beneath the floor in hopes the souls would be reborn (Ellis 1968).

The energy expenditure during the course of cremation and that it was a public event places the cremations in a special category of social distinction. How are these individuals related to those interred within structures? Were these families the highest-ranked lineages at the site? Were they outsiders who died away from home and had no formal place within the settlement? Or were they part of another ethnic group residing at the pueblo?

Rice (2016: 49) offers some interesting clues for understanding the purpose of cremation. He cites the Pee Posh’s two beliefs regarding cremation. First, people who were not cremated smelled in the land of the dead and were segregated from those who were cremated and could not participate in dances or games. Second, is the notion of reversal (or perhaps, reciprocity) mentioned above; that is, everything consumed by the fire in the world of the living was subsequently restored in the land of the dead. The first belief stands in marked contrast to the common Mimbres practice of interring the dead in the flesh beneath house floors which would negate the concern for smell. These fundamentally different beliefs would certainly suggest two separate ethnic groups occupying the NAN Ranch pueblo.

Not knowing what guided the behaviors during the course of preparing the corpse, choosing the location or room for burial, digging the grave or preparing the cremation pyre, placing the body, choosing associated symbolic items, placing the items in the grave, and what these behaviors may have stood for leaves any archaeological interpretation as speculation. We have to reach out to other Native American cultures for parallels to gain some kind of understanding from the Native American perspective.

Conclusions

Recent research has shown that Mimbres painted pottery was made by cottage industry ceramicists in villages located in the forested elevations of the Mimbres region, mainly in the upper Mimbres Valley (Creel and Speakman 2018). The assumption for the restricted production area is guided by the availability of wood needed for firing the pottery, something that would have been a valued commodity in the lower valley desert region. The production followed a tradition of white-slipped brownware that showed subtle stylistic changes through time (Shafer and Brewington 1995; Figure 2). The pottery was distributed across a wide area by a system that probably included both exchange and gifting. Mimbres pottery was not produced as mortuary ware. Once in the hands of the consumer the pottery went into household use as serving bowls, water jars, and storage containers, functional roles shown by archaeological context and use wear (Figure 5.11) (Lyle 1996). One final function of a selection of some bowls, however, was to kill the bowl and place it as a mask over the dead.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer / Western New Mexico University Museum.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Harry Shafer.

The practice of killing a bowl and placing it over the face or head as a mask was embedded in mortuary ritual and world view. Placing the bowl over the face was part of the transformation ritual, transforming the once living person to an ancestral spirit being. The interpretation here is that the perforated bowl was to provide a mouth for the mask to allow the ancestor spirit to breathe and communicate with the living. Placing the body beneath the floor returned it to the Underworld, the world of the dead. The floor vaults of certain rooms identified as corporate kivas served as the portal through which the communication could occur with ancestor spirits dwelling in the Underworld below (Figure 5.12). Placing deceased ancestors within the confines of private residential space also kept their secret knowledge and power in the possession of their lineal kin and to keep them close by, as argued by Petrovich (2001).

Not all of the dead were so treated, only select individuals, about 55%, interred beneath structural floors had bowl masks. That everyone was not treated the same by having a mask may be indicative of social differences and may have distinguished between those who had access to resources assigned to corporate groups through kinship association and those that did not. Assuming social distinction was marked by a mask is a trait not considered by any of the previous efforts to define social differences.

A subset of the mortuary sample was cremated, and treatment of cremated individuals was much different from that of those interred beneath structural floors. The various attributes represented in the cremation cemetery, primary cremation, secondary cremations marked by sherds from multiple vessels included in the cremation pyre, other artifacts were included in the secondary cremation pits such as pallets, shell ornaments, arrow points, and corn, a pattern strikingly similar to the cremation patterns among the Hohokam of southern Arizona, albeit the ceramics are almost exclusively Mimbres.

Note

1. NAN is the cattle brand for the Y-Bar NAN Ranch near Faywood, New Mexico. Ranches often use the brand for the ranch name.

Acknowledgments

Several individuals deserve acknowledgments for providing helpful comments or assistance during the course of preparing this chapter. Drs. James Farmer and Rex Koontz invited my participation in this book and made helpful comments and suggestions during the process. Dr. Darrell Creel assisted in preparing vessel figures and comment on earlier drafts of the paper, Dr. Frank A. Weir provided the drawing for Figure 5.3, and Dr. Cynthia Bettison at Western New Mexico University Museum for her usual help and guidance.

Works Cited

Anyon, R. and S. LeBlanc

1984 The Galaz Ruin: Prehistoric Mimbres Village in Southwestern New Mexico. Albuquerque: Maxwell Museum of Anthropology and the University of New Mexico Press.

Bartlett, S.

2013 Ancient Burial Rituals and Imagery: The Relationships of “Kill-holes” to Images on Mimbres Ceramic Bowls and the Ideology Behind Them. MA thesis, University of Oklahoma, Norman.

Brody, J. J.

2004 Mimbres Painted Pottery: Revised Edition. Santa Fe: School of American Research.

Burt, C. K.

2013 “Ritually Killed Ceramic Vessels in Mortuary Contexts Across the Prehistoric Southwest”. In Proceedings of the 17th Jornada Mogollon Conference, T. L. VanPool, E. M. McCarthy, and C. S. VanPool, eds., pp. 211-226. El Paso: El Paso Museum of Archaeology.

Cosgrove, H. S. and C. B. Cosgrove

1932 The Swarts Ruin: A Typical Mimbres Site in Southwestern New Mexico. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 15, No. 1. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Creel, D. C.

1989 “A Primary Cremation at the NAN Ranch Ruin, with Comparative Data on Other Cremations in the Mimbres Area, New Mexico”. Journal of Field Archaeology 16: 309-329.

2006 “Evidence of Mimbres Social Differentiation at the Old Town Site”. In Mimbres Society, V. S. Powell-Marti and P. A. Gilman, eds., pp. 32-44. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Creel, D. C. and R. Anyon

2003 “New Interpretations of Mimbres Public Architecture and Space: Implications for Cultural Change”. American Antiquity 68 (1): 67-92.

Creel, D., and Robert J. Speakman

2018 “Mimbres Pottery: New Perspectives on Production and Distribution”. In New Perspectives on Mimbres Archaeology, pp. 132-148, Barbara Roth, Patricia Gilman, and Roger Anyon, eds. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Ellis, F. H.

1968 “An Interpretation of Prehistoric Death Customs in Terms of Modern Southwestern Parallels”. In Collected Papers in Honor of Lyndon Lane Hargrove, Albert H. Schroeder, ed., pp. 57-76. Papers of the Archaeological Society of New Mexico No. 1. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press.

Gilman, P. A.

2006 “Social Differences at the Classic Period Mattocks Site in the Mimbres Valley”. In: Mimbres Society, V. S. Powell-Marti and P. A. Gilman, eds., pp. 66-84. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Gilman, P. A. and S. A. LeBlanc

2017 Mimbres Life and Society: The Mattocks Site of Southwestern New Mexico. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

Grieder, Terence

1965 “Report on the Study of the Pictographs in Satan Canyon, Val Verde County, Texas”. Texas Archeological Salvage Project Miscellaneous Papers No. 2, The University of Texas at Austin.

1966 “Periods in Pecos Style Pictographs”. American Antiquity 31 (5): 710-720.

1986 “Recording and Interpreting Lower Pecos Pictographs: Methods and Problems”. In Ancient Texans: Rock Art and Lifeway Along the Lower Pecos, Harry J. Shafer, ed., pp. 176-179. Austin: Texas Monthly Press.

Ham, E. J.

1989 Analysis of the NAN Ruin (LA15049) Burial Patterns: An Examination of Mimbres Social Structure. MA Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station.

Headrick, A.

1998 “The Street of the Dead…It Really Was: Mortuary Bundles at Teotihuacan.” Ancient Mesoamerica 10 (1): 69-85.

Hegmon, M., et al.

1999 “Scale and Time-Space Systematics in the Post-A.D. 1100 Mimbres Region of the North American Southwest”. Kiva 65: 143-166.

Lyle, R. P.

1996 Functional Analysis of Mimbres Ceramics from the NAN Ruin (LA15049), Grant County, New Mexico. MA Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station.

McAnany, P. A.

1995 Living with the Ancestors: Kinship and Kingship in Ancient Maya Society. Austin: University of Texas Press.

McGuire, R. H.

2001 “Ideologies of Death and Power in the Hohokam Community of La Ciudad”. In Ancient Burial Practices of the American Southwest: Archaeology Physical Anthropology, and Native American Perspectives, D. R. Mitchell and J. L. Brunson-Hadley, eds., pp 27-44. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Moulard, B. L.

1981 Within the Underworld Sky: Mimbres Ceramic Art in Context. Tucson: Twelvetrees Press.

Myerhoff, B. G.

1974 The Peyote Hunt: The Sacred Journey of the Huichol Indians. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Parks-Barrett, M. S.

2001 Prehistoric Jewelry of the NAN Ranch Ruin LA14049), Grant County, New Mexico. MA Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station.

Petrovich, S. N.

2001 Religious Determinants of the Spatial Aspects of Mortuary Behavior at the NAN Ranch Mimbres Site. M.A Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin.

Rice, Glen E.

2016 Sending the Spirits Hone: The Archaeology of Hohokam Mortuary Practices. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press.

Saxe, A. A.

1970 Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices. PhD dissertation, University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Scherere, A. K.

2015 Mortuary Landscapes of the Classic Maya: Rituals of. Body and Soul. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Shafer, Harry J.

1986 Ancient Texans: Rock Art and Lifeways Along the Lower Pecos. Austin: Texas Monthly Press.

2003 Mimbres Archaeology at the NAN Ranch Ruin. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

2006 “Extended Families to Corporate Groups: Pithouse to Pueblo Transformation of Mimbres Society”. In Mimbres Society, V. S. Powell-Marti and P. A. Gilman, eds., pp. 15-31. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Shafer, H. J. and R. L. Brewington

1995 “Micostylistic Changes in Mimbres Black-on-White Pottery: Examples from the NAN Ruin, Grant County, New Mexico”. Kiva 64 (3): 5-29.

Shafer, H. J., and C. K. Judkins

1996 “Archaeology at the NAN Ranch Ruin: 1996 Season”. The Artifact 34 (3 & 4): 1-62.