7 Wari and the Huaca del Sol: Max Uhle’s 1899 Textile Collection at Moche, Perú

Amy Oakland

https://doi.org/10.52713/QDMZ4161

Terence Grieder takes an important position in his essay “The Interpretation of Ancient Symbols”: an art historical investigator should consider both style and ethnology (1975: 853-854). At a basic level Grieder recognizes that characteristics in ancient objects continue to be meaningful today. I appreciated his active involvement in Andean archaeology, derived in large part from an early interest in the work of Max Uhle, which he encountered at the University of Pennsylvania while completing his PhD work. In an early collaboration with Grieder, I analyzed the textiles he had excavated at La Galgada, Perú (Grieder et al. 1988). In the present article I discuss textiles that Max Uhle excavated on the Huaca del Sol in the Moche Valley now housed in the museum of his patron Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology, at the University of California, Berkeley. Uhle catalogued only thirteen textiles numbered 4-2594 and 4-2595 A-L, all from the Huaca del Sol. The group is significant for the time period during when they were created – the Andean Middle Horizon (600-900 CE), when religious imagery from Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) was spread throughout Perú by the Wari (Huari), for the textile style and details of construction, and for the location on the north coast where Moche textiles are rarely preserved. The textiles identify at least three separate traditions found together: a locally-developed Moche style, a hybrid style with both highland and coastal characteristics, and a Wari-associated style. This article analyzes the textiles from the Huaca del Sol as an opportunity to examine relations between the two important Peruvian cultures of the Moche and Wari.

North Coast Moche and Highland Wari

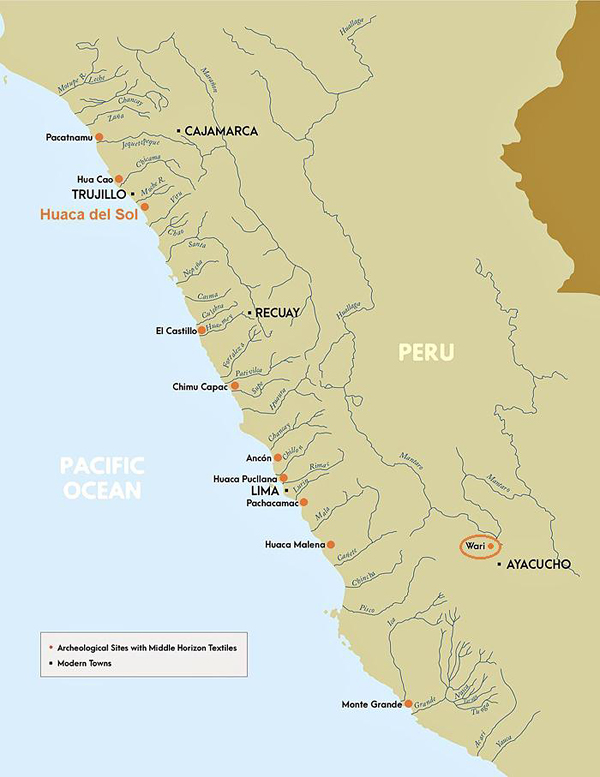

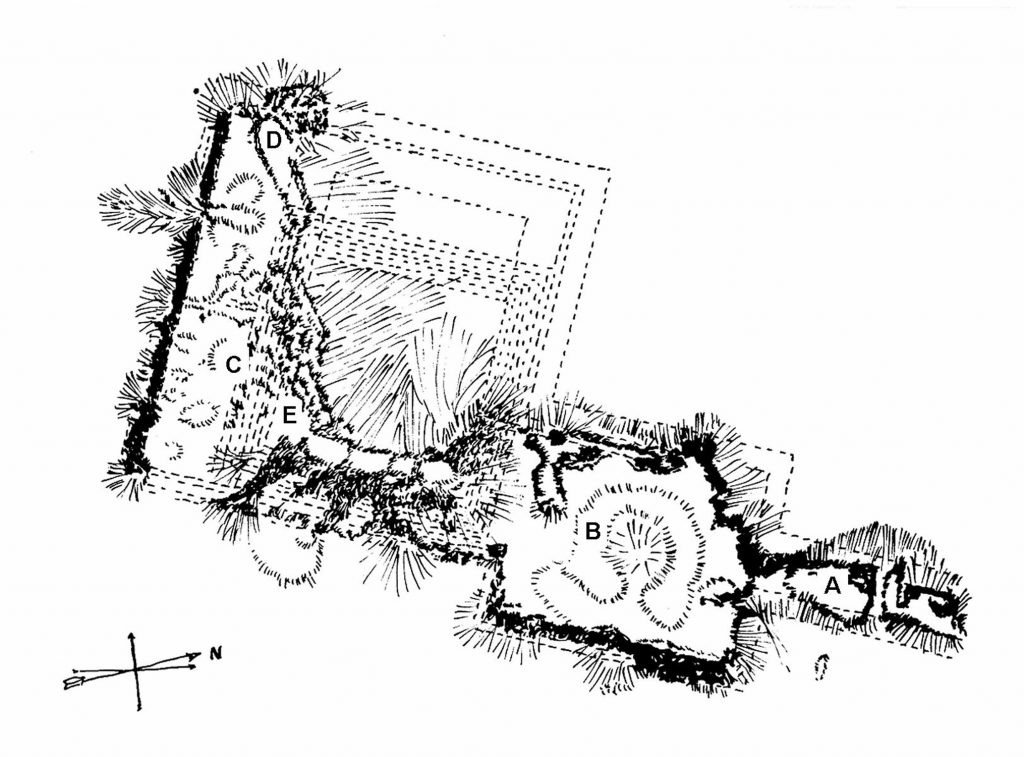

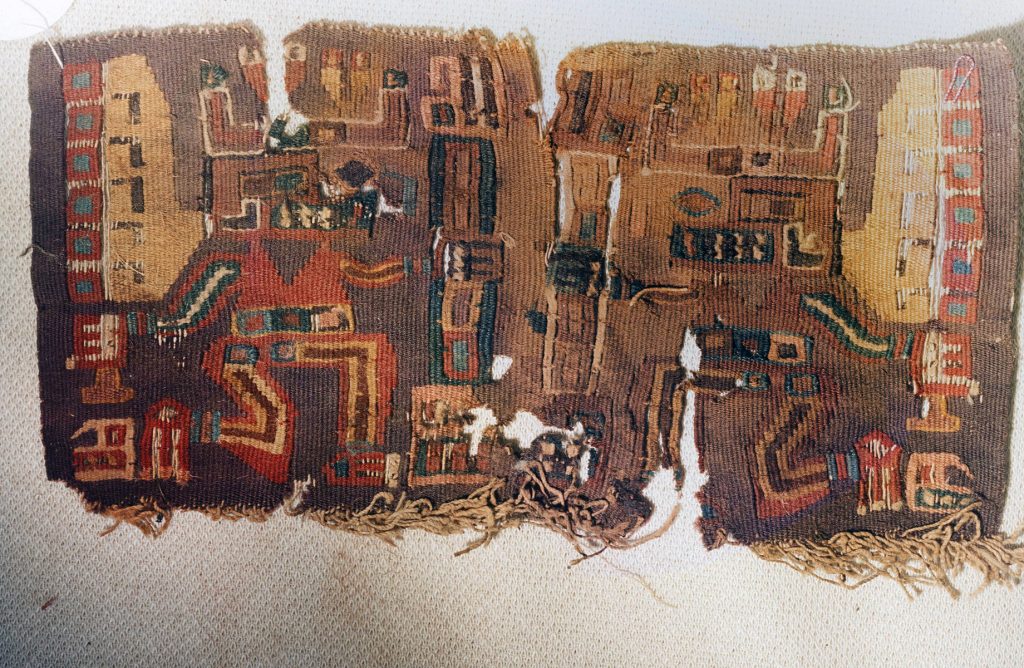

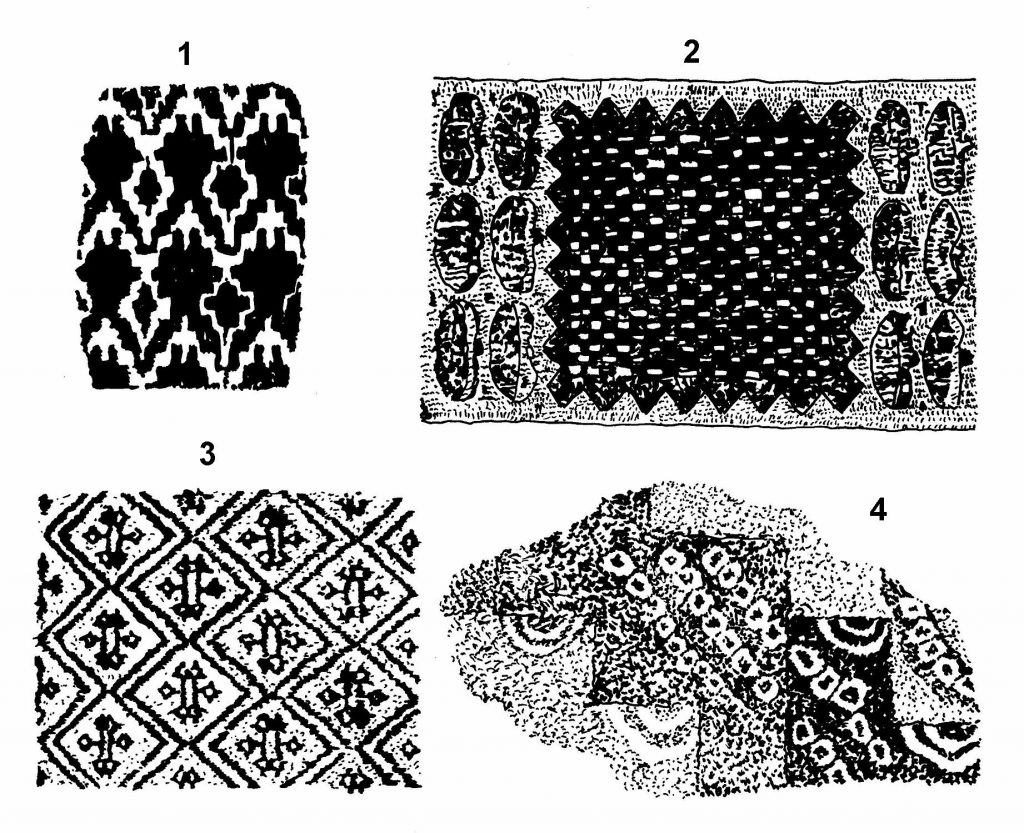

Uhle excavated at Moche during his first Peruvian expedition for the University of California, concentrating on monumental adobe structures called huacas along the lower Moche River (Figure 7.1) (Rowe 1954:7). His work began on August 26, 1899 and ended March 15, 1900 and included surveys, mapping, and two principal excavations (Kaulicke 2014). One excavation was in the early Moche Site F (300-600 CE), a cemetery platform near the Huaca de la Luna where he collected ceramics, metal, and stone objects (Uhle 1913: Fig.1). This article discusses Uhle’s excavation on the Südplateau or southern platform of the Huaca del Sol, marked C on his map (Figure 7.2) (Uhle 1913: Fig.3). The Huaca del Sol was the principal huaca during the late Moche period (600-900 CE) and one of the largest ancient constructions in the Americas.1 The Huacas Luna and Sol, together with an urban core, comprise the archaeological center now called Huacas de Moche (Figure 7.3). Uhle illustrated “Tiahuanacoid”/Wari artifacts that he collected in the Grabfeld or grave field on the southern platform including broken ceramics, a section of a carved wooden Wari cup, and a slit-tapestry textile with a Wari image (Figure 7.4) (Uhle 1913: Plate V b; Figure 16). He also published drawings of another four textiles fragments with local and Wari-associated styles (Figure 7.5) (Uhle 1913: Figure 17).

Map by Alicia Mattera.

A. Dam of ancient road

B. Northern plateau

C. Southern plateau with cemetery

D. Raised part of plateau

E. Pyramid.

Redrawn by Amy Oakland from: Max Uhle, 1913: Die Ruinen Von Moche, Fig. 3.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

1. Double cloth 4-2595C;

2. Openwork tapestry band ?4-2595H;

3. Supplementary-weft 4-2595G;

4. Wari tie-dye (s.n.).

Redrawn by Amy Oakland from: Max Uhle: 1913: Die Ruinen Von Moche, Fig. 17.

The Huacas de Moche have been considered the capital of a southern Moche state. Jeffrey Quilter and Michele Koons provide a description of the “complicated picture of the past in ‘Mochelandia’” and consider that Moche culture existed instead within multiple centers along the coast, sharing a Moche religious system, but differentiating themselves especially through distinctive ceramic styles as Christopher Donnan observed (Quilter and Koons 2012: 138; Donnan 2011). Northern Moche centers are often described within Early, Middle, and Late Moche ceramic phases while southern Moche ceramics have been related to a five-phase stylistic sequence Moche I-V. In an important recent study Koons and Brigit Alex reviewed radiocarbon dates associated with Moche ceramics and found that before 600-650 CE, “Moche people living in the various valleys seem to have been using regional ceramic styles,” but after this period a host of changes occurred; the Moche IV ceramic style was developed at the Huacas de Moche just before 600 CE and continued to be used there, never adopting the later Moche V style that was developed around 650 CE in the neighboring Chicama Valley (Koons and Alex 2014: 1050). Koons noted at the Moche site Licapa II in the Chicama Valley “both southern Moche IV and V and northern Late Moche styles of ceramics of the highest quality are found” and she suggests that “alliances and relationships crosscut the northern and southern Moche boundary” (Koons 2015: 61, 68). Koons and Alex (ibid: 1052) conclude that:

between 600-650 CE, Moche IV, V, and Late Moche are adopted at roughly the same time at different sites throughout the Moche world and suggest that political affiliation was more complex and extended beyond local spheres in this later Moche phase.

This is the period when the influence of the Wari, with its capital in the southern highlands, begins to be noticed within the northern valleys. Luis Jaime Castillo states that “around 650 CE things started to change rapidly in the Moche world, particularly in the Jequetepeque Valley” when Late Moche Fineline ceramics were adopted in elite tombs at San José de Moro along with a small group of Wari ceramics, Wari obsidian blades, Wari blackware keros (traditional Andean cups), and Cajamarca ceramics that Castillo suggests may have arrived through Wari exchange (2012: 53-55). From the evidence of burials at San José de Moro, Castillo concludes “Late Moche, Wari, Cajamarca, and Lima-were somehow connected” (ibid). Textiles have not survived in San José de Moro burials and they are rarely mentioned in excavation reports from Moche centers, but Uhle’s Huaca del Sol collection included both ceramics and textiles in Moche, Wari, Casma, and Cajamarca styles during the Late Moche period. The Huacas de Moche experienced the same dramatic events during the same time period. Between 600-650 CE the Huaca de la Luna was abandoned, ending the Early Moche period that featured Moche warriors, priests, and Moche gods in elaborate sacrificial rituals (Uceda 2008; 2010: 195-199). The following Late Moche culture continued for 150-200 years with a new urban focus, a new ruling urban elite, and the construction of the New Temple/ Plataforma III (Uceda 2010). The monumental Huaca del Sol was constructed during this late time and continued in use during the period known throughout Perú as the Middle Horizon ( 600-900 CE) (Tufinio et al. 2014).

Dorothy Menzel (1977: 59, note 191) identified these same late Moche and Wari connections where Moche V ceramics had been discovered together in tombs with Wari styles in the Piura Valley, Pacatnamu, and the Santa Valley. Ubbelohde-Doering’s Pacatnamu excavations contained Moche and Wari ceramic styles and textiles in the group Tomb E-1 where early Moche slit-tapestries were found with textiles that he described “as red and yellow, which are remarkably bright colours for the Mochica palette,” an observation that matches late Moche, Middle Horizon style (1967: 22-81). At San José de Moro, Moche artists copied a wide variety of Wari ceramic forms and themes in a combined Moche-Wari ceramic style (Castillo 2001, 2012). Although few textiles are preserved on the north coast, there is no reason to suggest that a Moche-Wari textile style would be “hypothetical” (Bernier and Chapdelaine 2018: 586). The opposite is now evident: a Moche-Wari textile tradition existed and products of this union have been discovered in large Middle Horizon cemeteries along the Pacific Coast (Oakland 2020b; Prümers 1990, 1995, 2001). The authors analyzed shared iconography and missed the structural information that identifies a Moche textile. Unlike spinning techniques used on the central and south coast and in the highlands, the Moche used a different method. Moche artists spin and weave with S-spun cotton yarns, a topic considered below. Ubbelohde-Doering’s Middle Horizon Moche textiles are similar to the large collection of hundreds of fragments of Moche-Wari textiles created by Moche weavers at El Castillo in the Huarmey Valley, analyzed by Heiko Prümers (1990). In addition, Middle Horizon Moche textiles have been discovered in non-Moche central and south coast burial sites together with Wari textiles, ceramics, and local styles (Oakland 2020a, 2020b). The small collection that Uhle excavated from the Huaca del Sol identifies this same Moche-Wari textile connection at Moche.

Spinning, Weaving and Moche Textiles

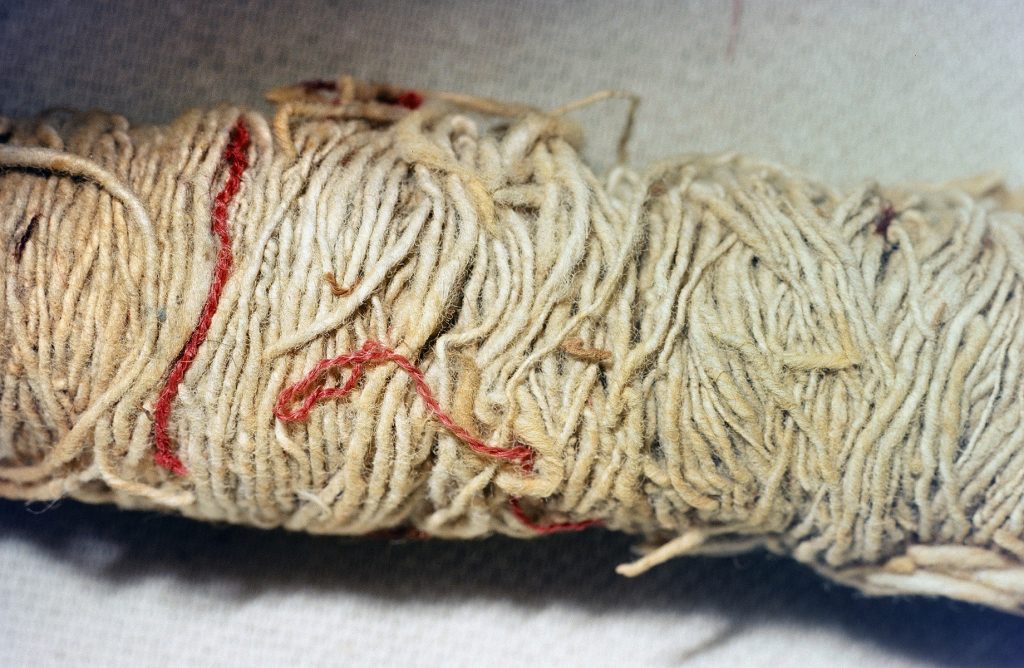

The foundation of Moche textile structure rests on S-spun cotton yarns used as singles or paired in cotton plain weave and sometimes plied S2Z, especially for use in slit-tapestry warp. This cotton tradition forms the basis of all Moche textiles and it has been identified in Early Intermediate Period Gallinazo weaving in the Virú Valley (Millaire 2009; Surette 2015).2 The style identifies a northern weaving tradition that followed in later Chimu textiles and persists today in regions of the Lambayeque and Jequetepeque valleys (Rowe 1984; Vreeland 1986). As James Vreeland describes, northern spinners hold their spindle horizontally often without a whorl and spin off the tip like Victoria Inoñaú Valdera from Mórrope, Lambayeque (Vreeland 1986). Figure 7.6 shows Valdera seated in front of her wooden tripod kaite that supports the copa, a roll of prepared cotton fiber in front of her. The position of the spindle is important and is the reason that the yarn produced will have fibers aligned in a right-slanted direction like the letter S. On the Huaca del Sol, Uhle collected a spindle filled with cotton yarn (Figure 7.7) where the S-slant of the white cotton fibers is visible (Figure 7.8). The small pieces of shiny red camelid, probably alpaca fiber, on this spindle were formed by two Z-spun yarns that have been re-plied Z2S, typical for almost all camelid fiber yarns. By comparison, this northern S-spinning cotton tradition contrasts completely with spinning traditions that continue in the highlands, where spinners use a drop-spindle like Florintina Huaman Condori from Pitumarca near Cusco (Figure 7.9). The drop-spindle is equipped with a whorl, is held vertically, and the yarn is drawn from the top, not the tip, producing a yarn aligned in the Z direction, usually plied Z2S. Spinners in both traditions twist the spindle in the same way, by sliding the spindle forward between the thumb and fingers, but if the spindle is horizontal and the fibers are drawn from the tip the yarn will have an S-spin, opposite from fibers drawn from the top of a vertically spinning spindle. These learned traditions have been passed through generations and remain regionally distinct. The most common Andean fibers are cotton on the coast and the hair from camelids in the highlands: llama for bags and rope, alpaca for fine textiles, and vicuña for the finest garments. Modern spinners also often use sheep’s wool.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Highland and coastal weaving techniques remain distinct as well. In Moropé, Victoria Inoñaú grows and spins native-colored cotton to use for contrast with white cotton and weaves in weft-patterned techniques. In the highlands near Cusco, Florintina Huaman weaves the opposite warp-faced patterns in alpaca and sheep’s wool for herself and her family. There are several loom types used in Perú today, but, interestingly, both Inoñaú and Huaman and their communities of weavers use the backstrap loom, the type pictured on the inside rim of a flaring Moche vase painted during the Late Moche period (Figure 7.10). Many people have discussed this image because it clearly depicts larger-sized men wearing wrapped and tied headcloths, and women of different ages with dark hair seated in front of their looms with the loom bars tied around their waists and attached to wooden roof supports.3 The vertical elements on the loom, called warps, are kept in tension by the weaver’s body as she holds shuttles filled with weft yarns that pass between the warp yarns to produce either plain weave, where both elements of warp and weft are balanced, or warp-faced weave where the warp is predominant, or weft-faced weaves where the wefts are predominant, as in a tapestry. To prepare patterns in warp-faced textiles, the warp will be selected in various colors that are pre-arranged in the warping process, a technique developed early in highland areas based on natural and dyed camelid fiber (Rowe 1977). Coastal weavers wove many styles, but they usually patterned textiles in weft-faced structures like those on the looms in the Moche vase painting. The loom’s simple construction belies the complex weaving structures possible.

Uhle and the Huaca del Sol Tiahuancoid/Wari Textiles

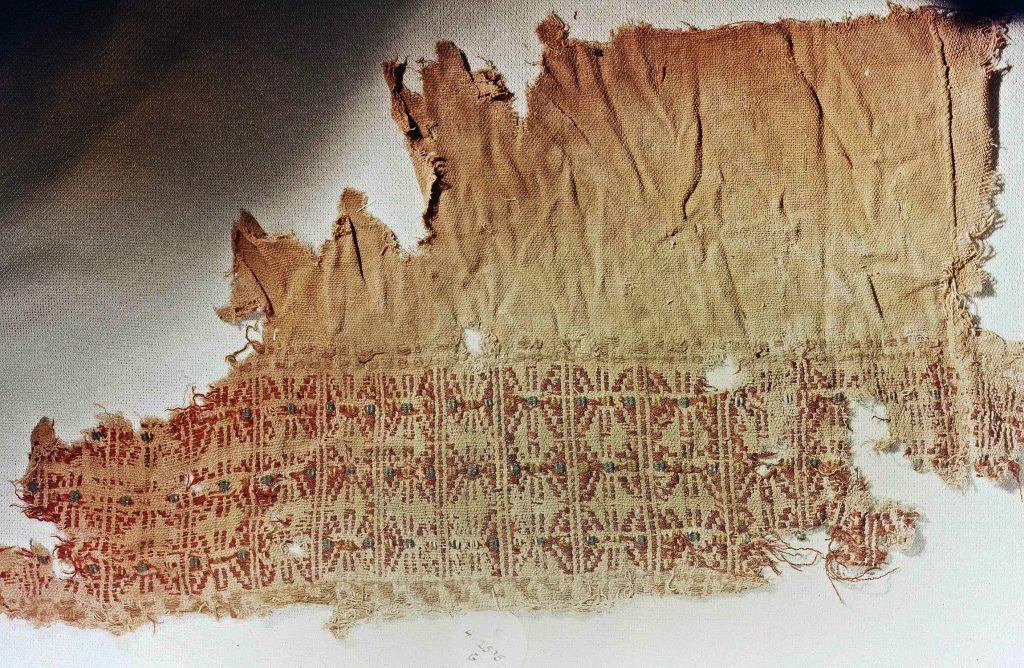

Max Uhle realized the differences in time between the two great huacas at Moche, noting that the Huaca del Sol had continued in use in the period of Tiahuanaco while “the Huaca de la Luna lay untouched in the Valley of Trujillo when a newer culture was taking place” (Uhle 1913: 110). Uhle concentrated excavations in the Grabfeld or cemetery of what he thought were sacrificial burials on the surface of the Südplateau, the wide southern platform of the Huaca del Sol (Kaulicke 2014; Uhle 1913).4 He published illustrations of what he called “Tiahuanaco” artifacts from the Huaca del Sol and stated “I was able to find numerous remainders of artifacts of the Tiahuanaco period, enough to use as hard evidence for the use of the grave field in this period” (Uhle 1913: 113, Fig. 16). Uhle is using the name Tiahuanaco for the Wari-style artifacts that he excavated on the Huaca del Sol because at this early date the Wari capital had not yet been identified in the southern highlands near Ayacucho (Rowe 1998: 12). Before excavating Moche, Uhle had studied stone sculpture at Tiahuanaco in Bolivia in 1894-1895 (Rowe 1954: 5-6). When he excavated Pachacamac in 1896-1897, he discovered Tiahuanaco/Wari artifacts and when he found similar objects on the Huaca del Sol he compared them to specific examples from his Pachacamac report (Uhle 1903). Lila O’Neale (1946, 1947) was the first to examine Uhle’s Moche collections at the University of California from both the Early Moche Site F and the Huaca del Sol. In the early Moche collection, O’Neale (1946) identified textile evidence on tiny fragments attached to metal objects where she recorded cotton yarns spun in the S direction and woven textiles in plain weave, twill, tapestry, double cloth, and supplementary-weft structures. O’Neale and Kroeber (1930: 43-44, Figs. 12 and 13) analyzed two of Uhle’s late Moche textiles collected from the Huaca del Sol. They stated that the structure of discontinuous-weft color spots they called “embroidered raised dots” in textile 4-2595g (Figure 7.11) must be considered unique to Moche textiles. The color spots or dots are not embroidered, but instead are integral to the weaving process and the structure does appear to be a technique created and used extensively by Moche weavers (Conklin 1979; Prümers 1995, 2007). Together with the slit-tapestry 4-2594, O’Neale and Kroeber (1930, op cit) discussed Uhle’s Huaca del Sol collection as evidence of “Tiahuanacoid Moche”.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Alfred Kroeber (1925: Plates 63-66) illustrated Uhle’s Huaca del Sol ceramics as examples of “Tiahuanacoid-ware.” Menzel also illustrated and discussed Uhle’s collection in relation to ceramics of the early epochs of the Middle Horizon, including Wari keros, Cajamarca ceramics, face-neck jars, Casma-style press-molded and incised bowls, and Moche clay musical instruments (Menzel 1977: Figs. 80, 82-86, 89, 92-93). Through stylistic analysis, Menzel (ibid: 37) determined that the press-molded ceramics excavated in sealed tombs dated to later Middle Horizon epochs, but that the collections from the surface of the Südplateau, including the fragments of Moche and Wari ceramics, the fragment of a carved wooden Wari cup, and the slit-tapestry, all dated to early epochs of the Middle Horizon. Uhle noted this same time difference when he distinguished the Huaca del Sol Grabfeld collection of broken pottery and textile fragments from complete ceramics that he excavated within enclosed tombs (1913: 111). He thought that the destroyed Grabfeld was earlier and as evidence he said that he found fragments of Tiahuanaco/Wari cups spread across the plateau and that a shard of one of the same cups had been walled into the closing wall of a tomb suggesting that the burial ground was destroyed before the sealed tombs had been constructed.

The Südplateau measured 136 m. long x 29 m. wide with some stratigraphy in the 80 cm fill (Uhle 1913: 110-113). In the bottom layer Uhle found thousands (my emphasis) of fragments of clay trumpets in “horn-like and shell form, the finding of which curiously makes one think of an earlier sacred place,” a comment that appears particularly fitting for the dramatic southern platform. He thought the evidence pointed to a demolished cemetery:

In general, all of the graves up to the last are destroyed, and it seems for a long time, that the former history of the grave field must be reconstructed out of debris… I was able to find numerous artifacts of the Tiahuanaco period in the open grave field (ibid).

He noted that “with the Tiahuanaco-like remains go together in the same bottom a lot of fragments that belong to other cultures”, and he specifically stated that mixed in the Grabfeld of the Südplateau he found “textile fragments, threads, pieces of reed, parts of human and animal bone, and numerous fragments of vessels, and other decorative objects” (ibid: 113).

Uhle’s excavations were the only ones to discover Wari and associated Middle Horizon material at the Huacas de Moche until new excavations on the Huaca del Sol by Moisés Tufinio and his collaborators, who excavated the area where Uhle worked on the southern platform now called Sección 4 (Tufinio et al. 2012, 2014; Uceda et al. 2016). Tufinio describes evidence of occupation, administration, storage, banquets, and feasting on the west side of the southern platform, and ritual activity and burials concentrated on the east side, which is now called Unidad 1. Tufinio excavated three tombs and discovered burials scattered across the platform’s width under the same shallow layer of fill. Unlike Uhle, who did not record any burial associations in the debris on the southern platform, Tufinio (2014: 150-158) was able to separate burial remains and associated material into ten Groupos and twenty Pozos where he uncovered human and camelid remains, fragmented ceramics, gourds, foodstuffs, and textiles. Mixed with this material, he collected over 500 fragments of the same musical instruments in all levels of all contexts and the same small quantity of Wari and Cajamarca ceramic styles, local ceramics, hybrid styles, and textiles similar to the types that Uhle excavated in the same location a hundred years earlier (Cruz et al. 2019; Pariona n.d. 2021; Tufinio et al. 2014). In addition, excavations within Moche habitation areas uncovered Middle Horizon and Wari related artifacts including Wari keros and Cajamarca ceramics in the urban sector (Cruz et al. 2019; Zavaleta et al. 2013, 2014).

Textiles from Uhle’s 1899 Excavations on the Huaca del Sol

On the Huaca del Sol, Uhle recovered textiles, yarn, and basketry fragments mixed with ceramics, human and animal remains. In addition to the spindle (Figures 7.7 and 7.8), Uhle cataloged two reed basketry samples 4-2597A-B, one coiled and the other woven in a twill pattern. He did not specify if the nine pairs of small cotton skeins 4-2596 (Figure 7.12) were discovered together, but they are wound in a similar manner and size and are all S-spun cotton yarns in natural white, brown, and dyed blue. Two important fragments, the openwork band and the Wari tie-dye (Figures 7.5:2, 7.5:4) are not located in the museum at present, however these textile types are easily recognized and Uhle compared each one with published examples that he had excavated at Pachacamac as discussed below.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Wari-associated Textiles, Südplateau Huaca del Sol: Tapestry, Tie-dye and Openwork

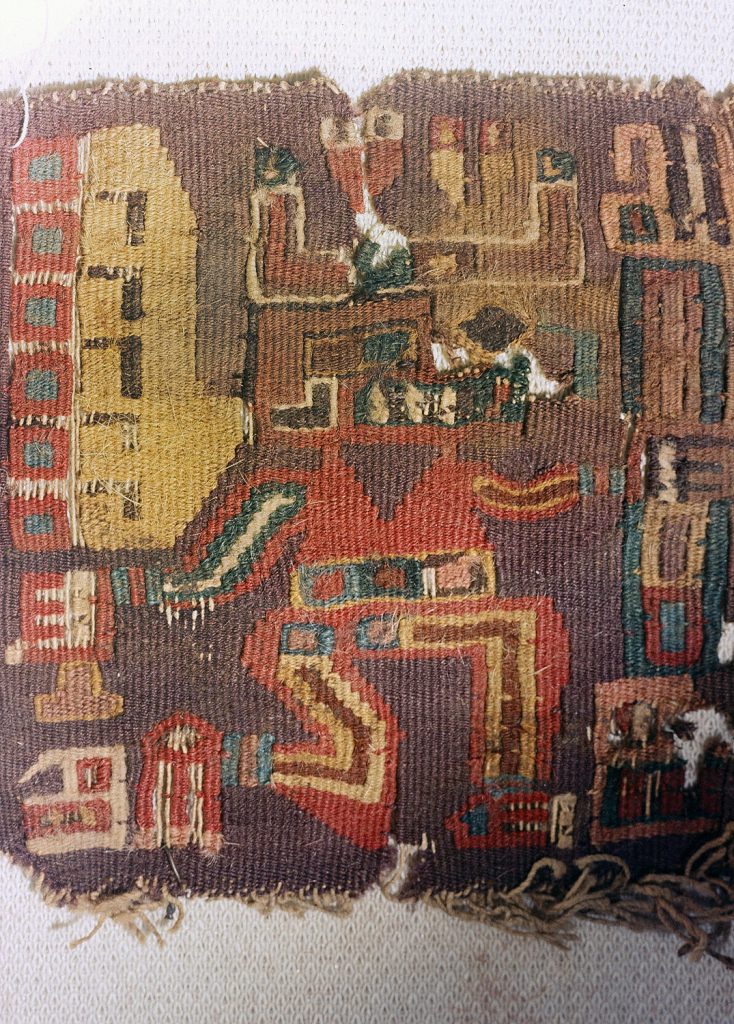

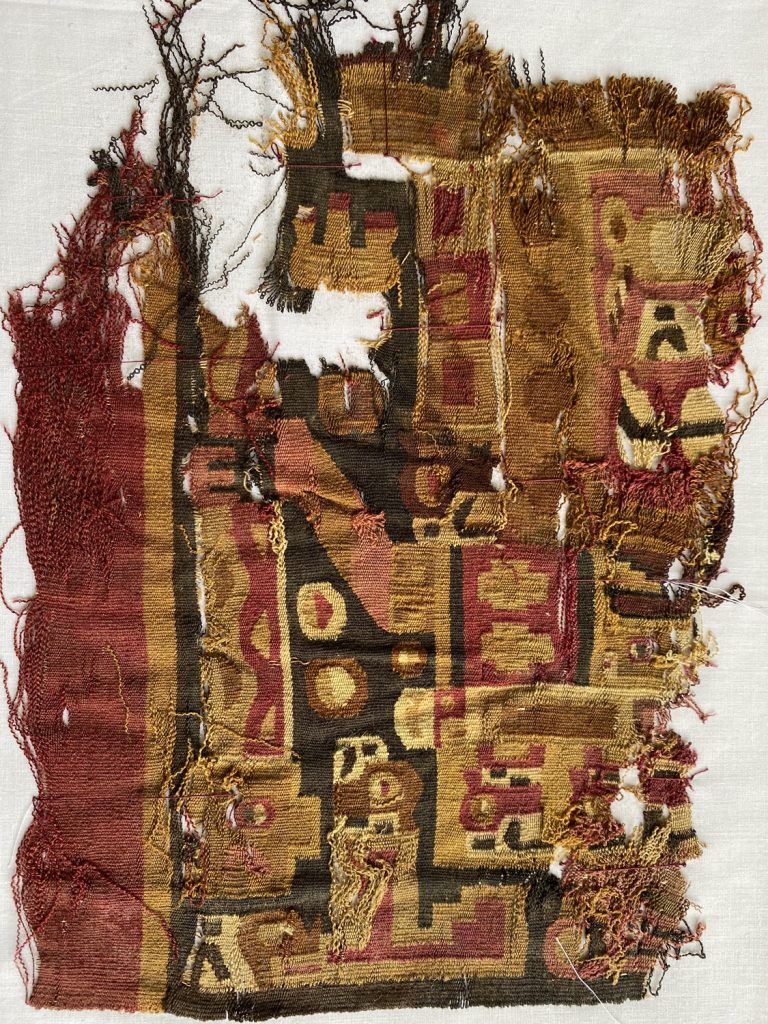

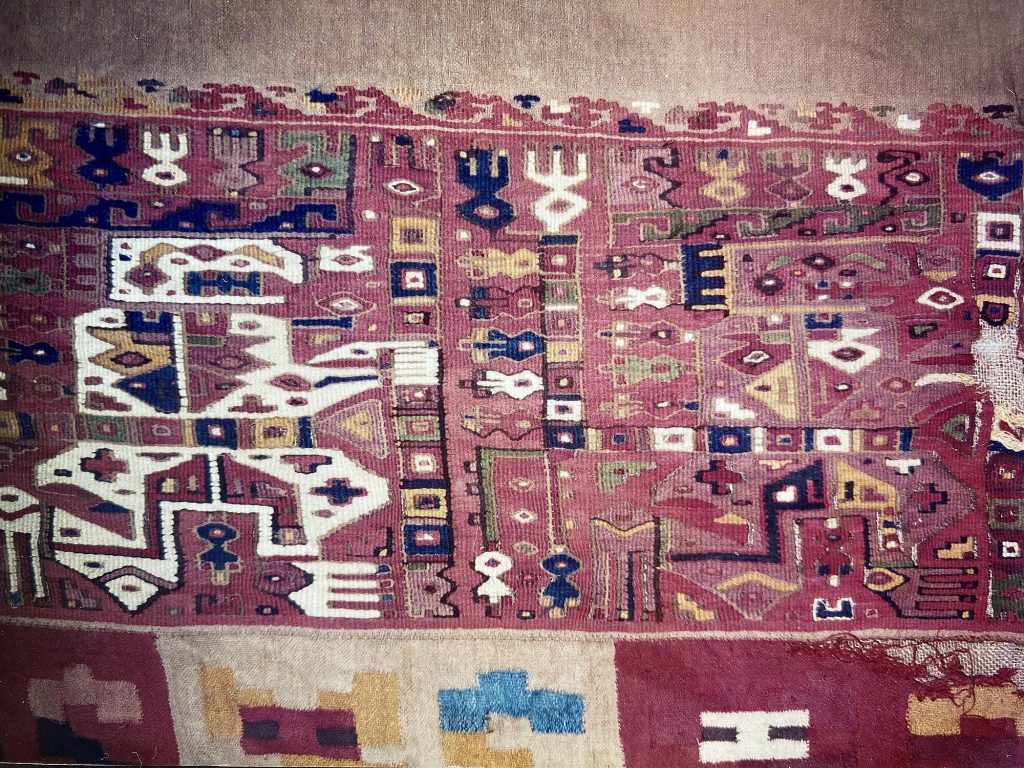

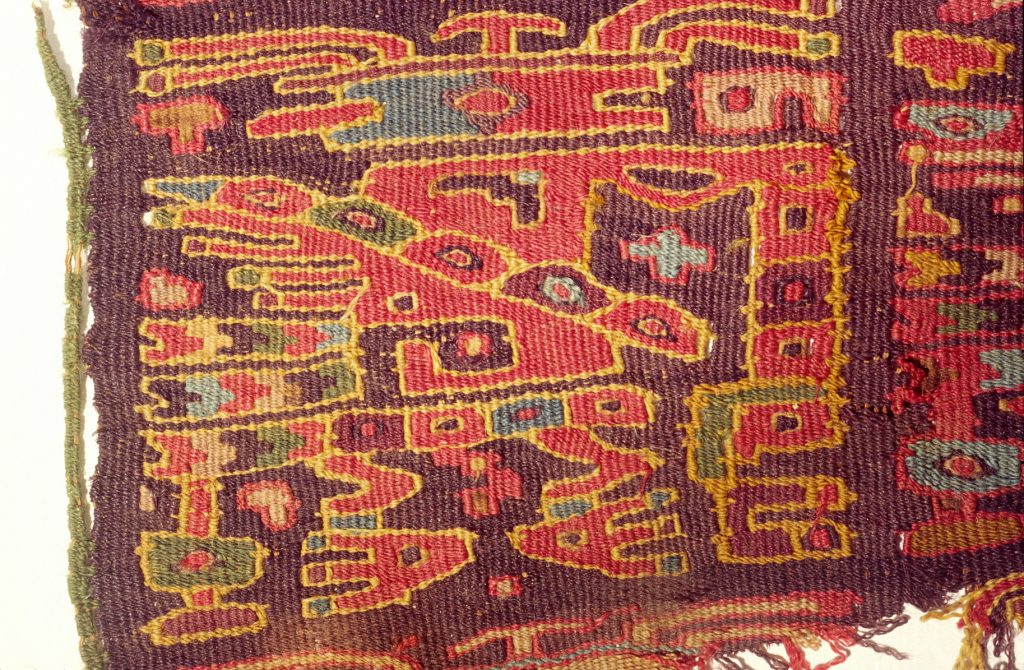

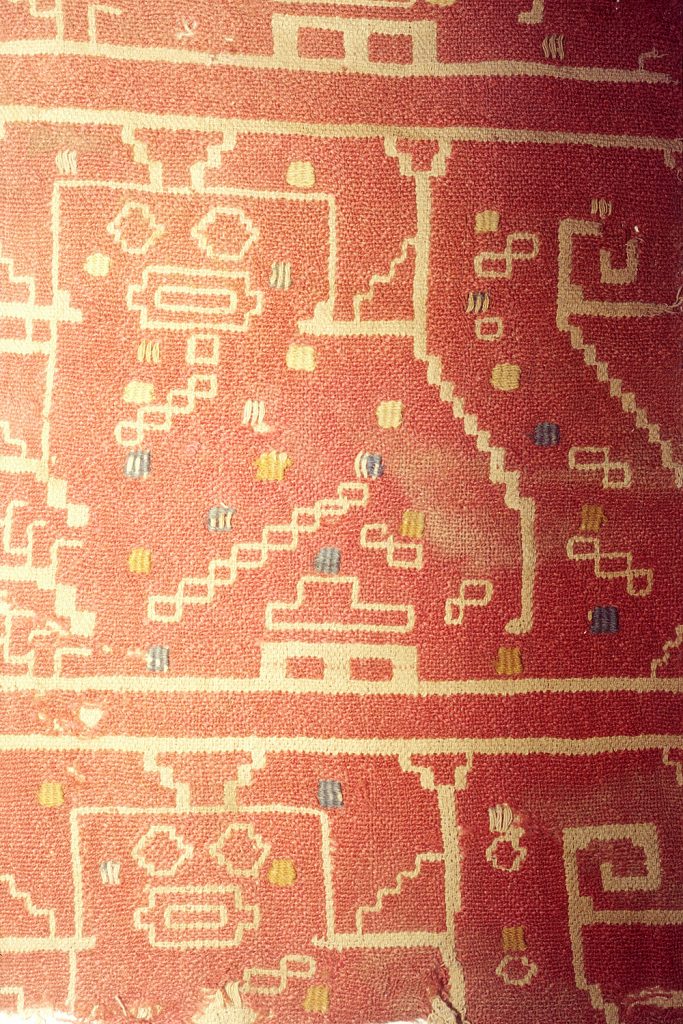

Uhle (1913: 113, note 2) specified that the Huaca del Sol slit-tapestry 4-2594 (Figure 7.4) “compares with the winged figures of the big monolith gate in Tiahuanaco”, as well as a fragment of a Wari weft-interlocked tapestry tunic that he excavated at Pachacamac and illustrated as a complete design block in a drawing (Uhle 1903: Plate 4, fig.2). Even from the drawing in his report and the small Pachacamac fragment no. 26718 (Figure 7.13), it is clear that the Pachacamac textile was originally part of a Wari tapestry weft-interlocked tunic similar in image and color to a Wari tunic fragment (Figure 7.14) from Tomb 1 at El Castillo in Huarmey (Prümers 1990, Band 1: 21, Abb. 271-272; 2001: Fig. 19). Wari weavers used an interlocking tapestry technique that links each weft yarn between warps before turning back to create color areas. The Huaca del Sol slit-tapestry 4-2594 is not Wari tapestry, but instead a Moche, coastal slit-tapestry type with Wari-inspired standing winged figures (Figure 7.15) woven as a small, complete textile patch with S2Z-spun white cotton warps. The slits are visible in the Huaca del Sol tapestry where wefts turn back without linking between color areas. Slit-tapestry is a coastal tapestry technique not unique to Moche, but the S2Z cotton warps are yarn types created by Moche spinners. The Huaca del Sol tapestry has cut warps visible on the bottom of the tapestry that might have been folded under and sewn below the neck on a man’s shirt (Donnan and Donnan 1997: Fig. 27; Oakland Rodman and Fernandez 2001: Figs. 27-29). This is the textile that Menzel (1977: 39-40: Fig. 89) describes as early Wari-related Middle Horizon 1B with two standing, facing winged figures holding staffs ending in human heads.

Courtesy of the Penn Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Uhle illustrated two additional textiles that are related to Wari style, a tie-dye fragment woven with discontinuous warps and wefts that he called “partly painted” and an openwork tapestry band (Uhle 1913: 113-114, Fig. 17.1-4). He stated that the tie-dye fragment Figure 7.5.4 was like Pachacamac textile 29782 (Figure 7.16) with hooked sections woven with discontinuous warp and weft technique (Uhle 1903:32, Fig. 31).

The technique of discontinuous warps and wefts is not confined to Middle Horizon textiles or to Wari, but it became particularly associated with Wari and is painted on Wari ceramic figures as a principal garment worn by elite men. It was woven in stepped or hooked sections and often tie-dyed in brilliant colors (Rehl 2006; Rowe 2012: Figures 181-190). Ann Rowe (2012: 201) suggests that the style possibly originated in “far southern Peru”, and was spread by Wari in the Middle Horizon. Uhle excavated several examples at Pachacamac with stepped tie-dyed sections like no. 29783 (Figure 7.17) similar to the Huaca del Sol tie-dye, and he states that at Pachacamac another tie-dye textile “was found upon a mummy under a poncho of pure Tiahuanaco style.”5

Courtesy of the Penn Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Courtesy of the Penn Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

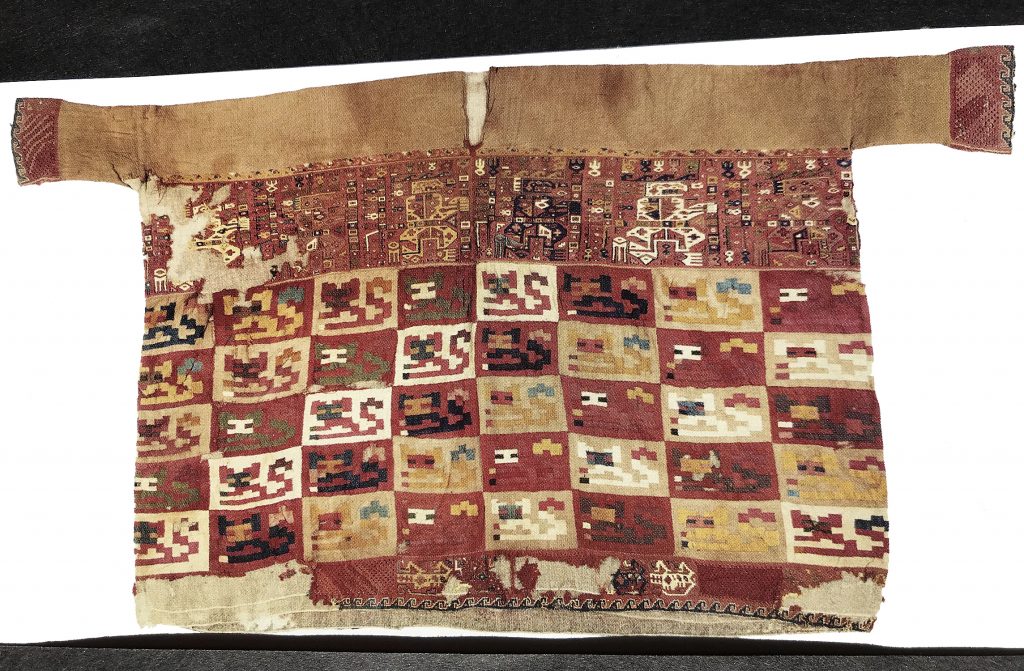

Uhle illustrated a drawing of another Middle Horizon textile, the openwork slit-tapestry band with rows of repeating beans (Figure 7.5:2) (1913: Fig. 17.2). He stated that this Moche textile was familiar to him from his Pachacamac excavations as the type “constitutes a characteristic of the period” and he noted that the Moche band “has the identical technique” as a narrow band no. 29673 (Figure 7.18) illustrated in his Pachacamac report (Uhle 1913: 114; 1903: 31, pl. 6, fig. 7). The Pachacamac band is also very similar to an openwork fragment from El Castillo (Figure 7.19) woven in slit-tapestry with alpaca yarns over S2Z cotton warps (Prümers 1990: Abb. 82). In this style, tapestry sections alternate with rectangular openwork areas where wefts are pulled together tightly leaving wide, open slits to create a grid-like decoration. These bands would have originally been woven for garments, especially tunic borders like the borders on a complete Moche sleeved-shirt (Figure 7.20) that Uhle excavated at Chimu Capac in the Supe Valley. In addition, the bands are often discovered in burials already removed from original garments (Menzel 1977: Fig. 77; Oakland 2020b: Fig. 15; Uhle 1903: Pl. V1). The openwork slit-tapestry technique was woven in many different iconographic styles and, like the tie-dye, are particularly representative of Middle Horizon Wari textiles.

Courtesy of the Penn Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Courtesy Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California.

Late Moche Textiles, Südplateau Huaca del Sol: Supplementary-weft and Double Cloth

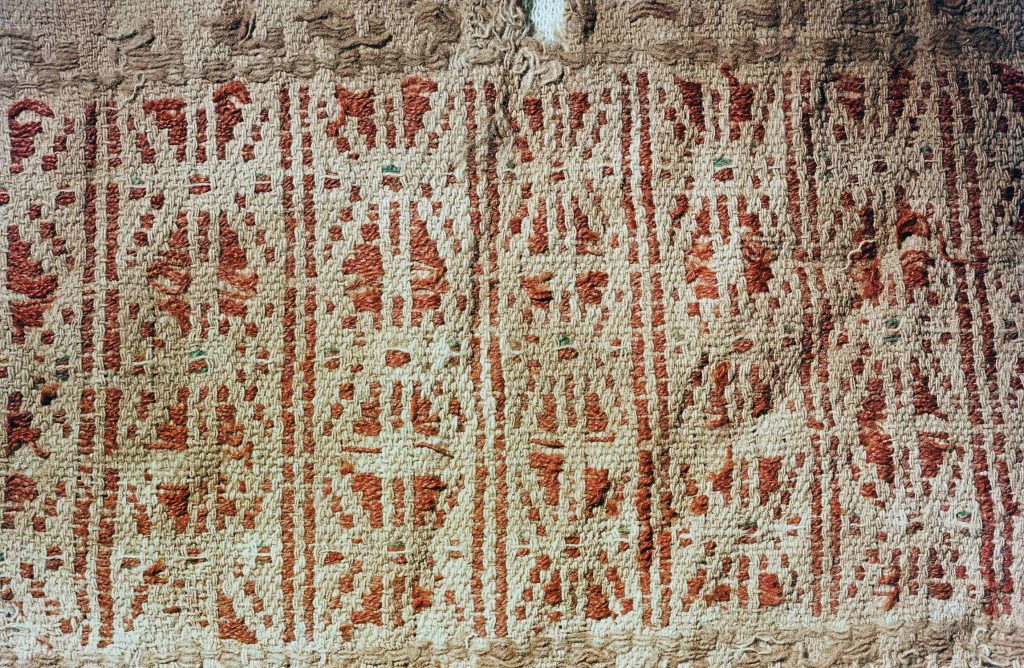

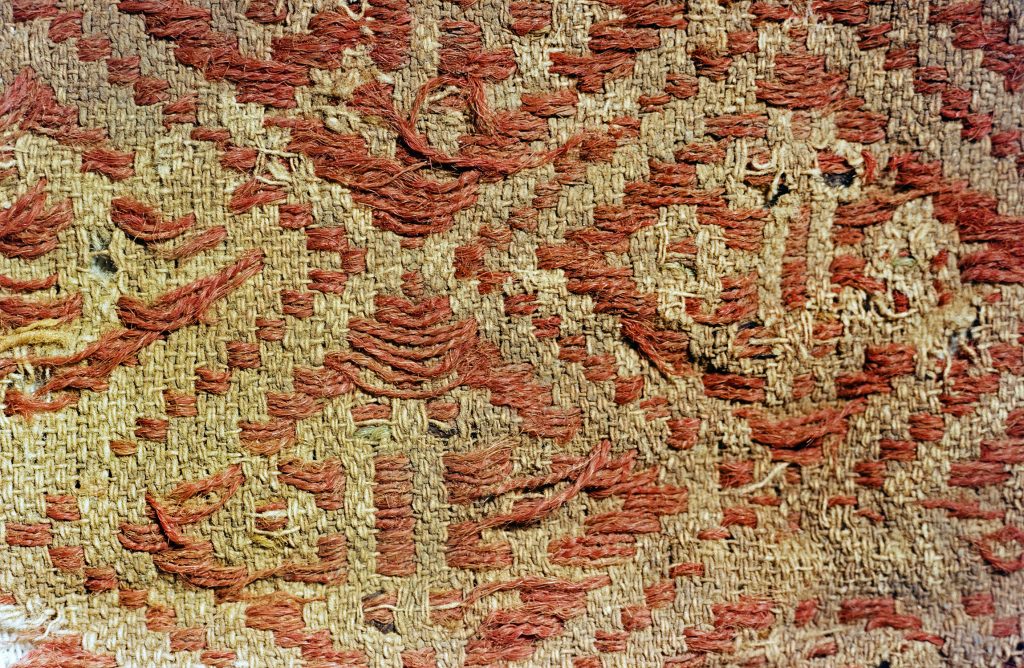

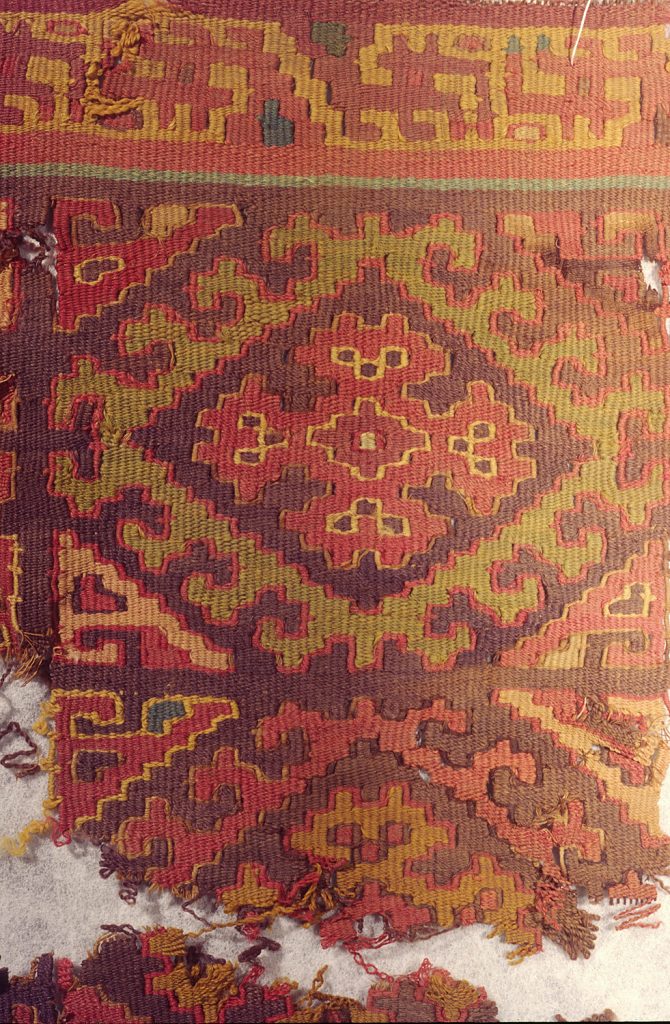

The other two Huaca del Sol textiles that Uhle called “partly double weave” include one double cloth (Figure 7.5:1) and one patterned with supplementary-wefts (Figure 7.5:3). These two fragments are related to a third Moche textile that Uhle excavated on the Huaca del Sol also woven in supplementary-weft patterning (Figure 7.11) (O’Neale and Kroeber 1930: 43-44, Fig. 12; Uhle 1913: Fig. 17.1, 3). These three textiles 4-2595 C, D, and G form their own group of local late Moche coastal-style (Conklin 1979: Fig. 10). Textile 4-2595G (Figures 7.11 and 7.21) and fragment 4-2595D (Figures 7.22-7.23) share similar structural features with white cotton plain weave woven with S-spun yarns paired in warp and single in the weft with the addition of paired Z2S red-dyed alpaca fiber used in supplementary wefts. In both textiles, the images repeat in rows of small patterns and in a diamond grid with discontinuous-weft color spots in blue, green, and gold alpaca yarns.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

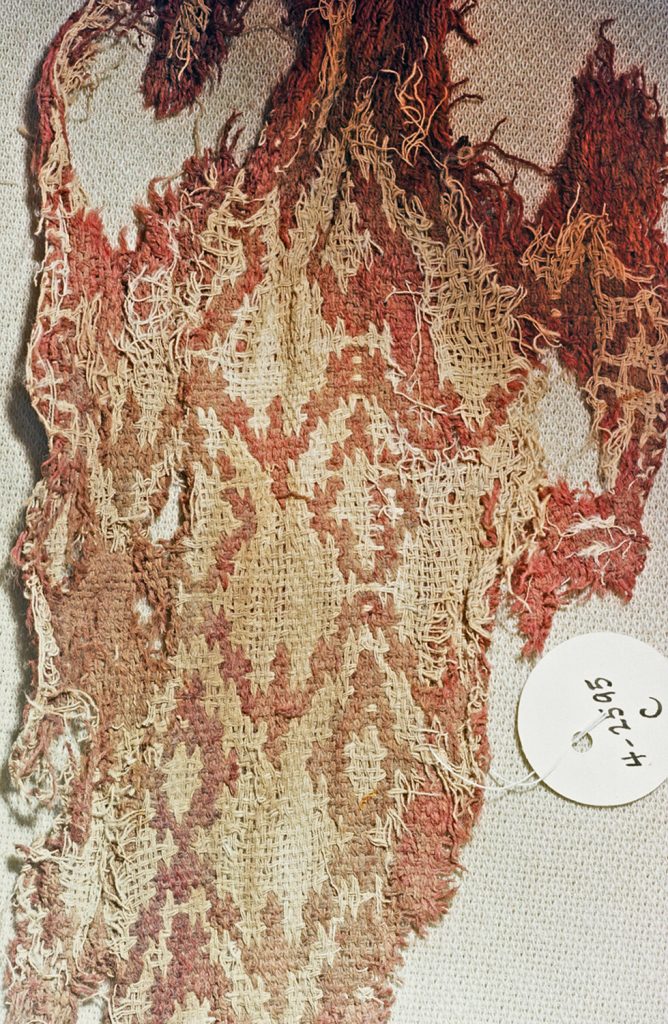

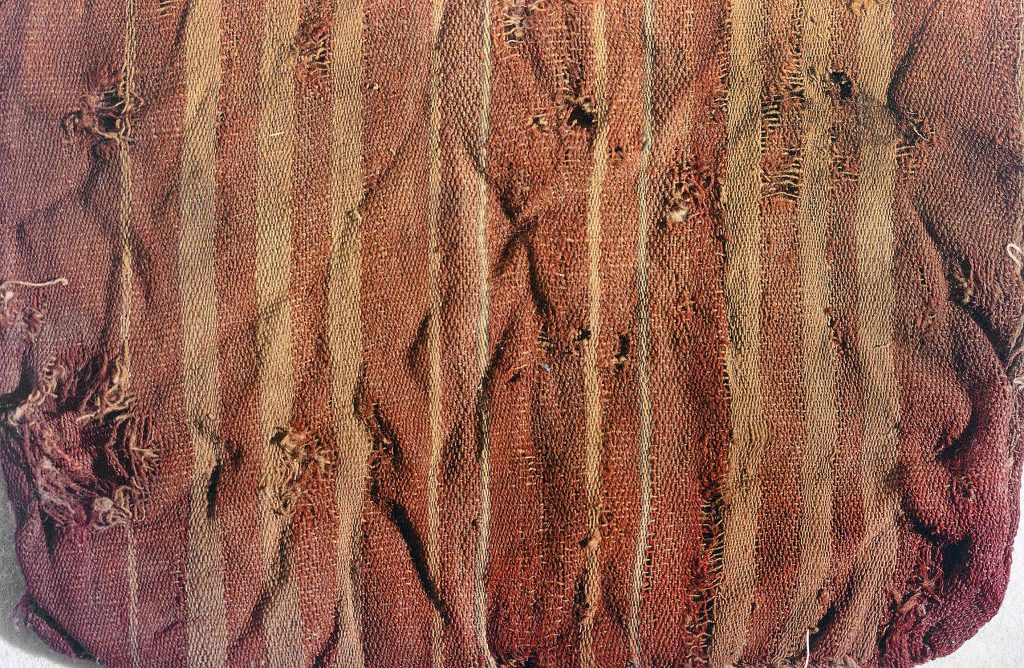

The third late Moche Huaca del Sol textile 2595C (Figures 7.24-7.25) is woven in double cloth in paired Z2S red alpaca and paired S-spun white cotton with the addition of color spots of blue alpaca Z2S in discontinuous wefts. The image of repeating catfish or stingrays in an overall diamond grid pattern relates closely to early Moche-style textiles from the Huacas de Moche, described by Fernández (2008), woven with fine S-spun brown and white cotton yarns and with discontinuous-weft spots in red camelid fiber. Jean-Francois Millaire (2009) and Flannery Surette (2015: Fig. 137-138) identified a similar blue and white double cloth cotton textile from the Early Intermediate Period site Huaca Santa Clara in the Virú Valley with similar catfish motifs in diamond pattern.6 Early Moche textiles like these Huacas de Moche and Viru Valley examples are woven principally in cotton, in diamond-grid layout with dots of dyed camelid fiber for color. During this early period the small amounts of camelid fiber are usually spun S2Z. Uhle’s Huaca del Sol textiles were woven with supplementary weft patterning and in double cloth with images that repeat in a diamond grid like these early Moche textiles, but the use of a much larger quantity of Z2S-spun and brilliantly dyed camelid fiber and the Wari associations on the Südplateau determine their late Moche, Middle Horizon period. The close similarity in style suggests very few generations separating these early and late Moche textiles at Moche.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Highland-related Textiles, Südplateau Huaca del Sol Warp-faced

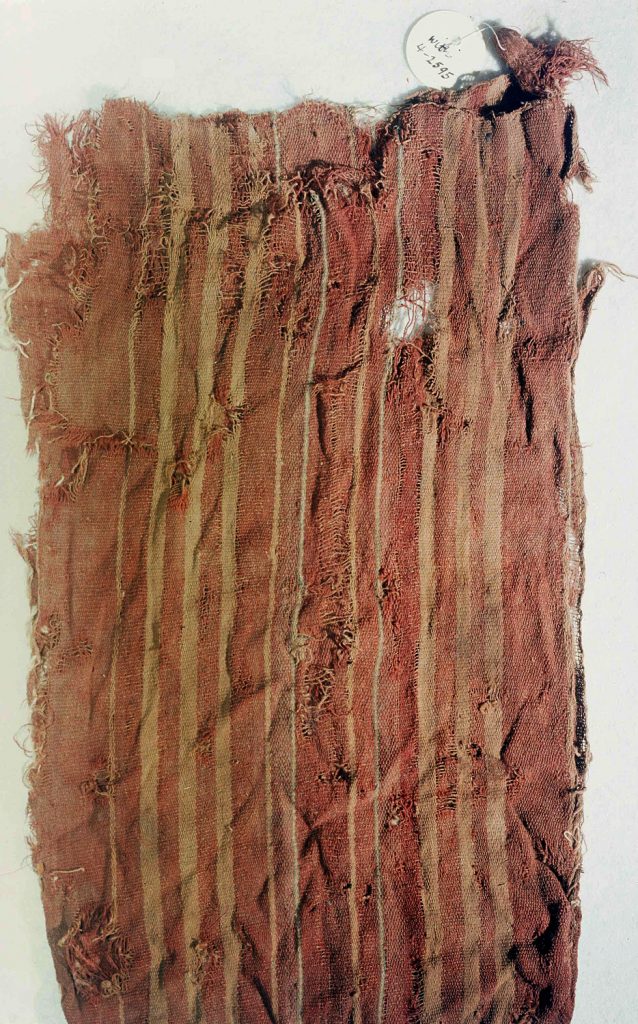

The last four Huaca del Sol textiles form a distinct group with no Wari imagery. These textiles are woven primarily in Z2S camelid fiber and are predominately warp-faced, an opposite tradition originating from a still undetermined area of the highlands (Rowe 1977). The two narrow bands 4-2595E and 4-2595F (Figure 7.26) use red camelid-fiber in both warp and weft, an unusual feature to weave dyed yarns in the mostly hidden weft of a warp-predominant structure. Both bands are woven with long, paired white S-spun supplementary cotton yarns that float on the back and are brought forward in small areas to create outlines of circles.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

The striped camelid-fiber textile cataloged as 4-2595L (Figures 7.27, 7.28) is woven with the addition of thin cotton warp-stripes in blue and white S-spun cotton with brown S-spun cotton weft. The use of cotton for weft and cotton mixed with alpaca warp stripes is not common to either Moche textiles or to textiles considered completely highland. The S-spun cotton probably identifies a local textile style with highland connections at this time period at Moche. For the Viru Valley Early Intermediate site of Huaca Santa Clara, Flannery Surette (2015) attributes the large quantity of camelid-fiber warp-faced textiles to its mid-valley location with access to the adjacent highlands. Surette (2015: 201, Fig. 295, 300) also describes a particular long, narrow, warp-striped, all camelid-fiber bag that she considers an import into Huaca Santa Clara. In shape and design the bag relates to the last textile collected by Uhle on the Huaca del Sol labeled 4-2595K (Figures 7.29, 7.30). But Uhle’s Moche bag is woven with both cotton and camelid fiber warp-stripes and S-spun cotton weft. This mixture perhaps identifies a late Moche population at Moche with skills and access to resources of both traditions of the highlands and those of the north coast.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Discussion: Wari at the Huaca del Sol

These fragmented textiles originally formed parts of burial offerings that Uhle stated were found together with human and camelid remains, ceramic sherds, and with thousands of broken clay musical instruments scattered across the southern platform. The original burial form was destroyed, but Uhle recognized the artifacts as similar to those from funerary bundles that he excavated at Pachacamac and later at Chimu Capac, where he also recorded opened tombs with contents scattered, skeletons altered, skulls removed, ceramics broken, and textiles cut and torn, including shattered Wari material mixed into the cemetery debris (Oakland 2020b). The Huaca del Sol was undoubtedly visited continuously and the remains on the southern surface may have been desecrated over centuries. Colonial glass was discovered in the recent excavations and today the huaca continues to be a sacred space for local rituals. Even so, Tufinio (2014: 153-154, Figure 73) was able to detect some burial associations and he illustrated a brocaded textile of Moche-Wari style that he stated was found together with Wari and Cajamarca ceramics.

Menzel (1977: 37) described the Huaca del Sol as “one of Uhle’s most important excavations” that reflected “changes in north coast culture history over a period of about 400 years” before, during, and just after the Middle Horizon. In particular, Menzel (1977: Figs. 80, 82-86) serrated the images molded into clay musical instruments finding that the faces of Moche gods were altered through Wari influence during the Middle Horizon. The thousands of fragments of these Moche trumpets and whistles “demand attention” as Dianne Scullin and Brian Boyd (2014: 376) suggested. Public rituals must have been staged on the wide southern platform of the Huaca del Sol involving large numbers of people. Loud and disruptive in sound (Scullin and Boyd ibid), these clay instruments have been excavated throughout the Huacas de Moche during early and late periods and recovered in a late Moche ceramic workshop within the urban sector (Bernier 2010: Fig. 8). Uhle’s textile sample also identifies styles that suggest a continuation of early Moche techniques into the Middle Horizon. The local Moche double cloth and supplementary-weft patterned styles are a direct continuation of early Moche textiles with the addition of a larger quantity of red, dyed camelid-fiber instead of the usual cotton warp and weft used in the earlier period. The Wari tie-dye textile was imported from the south where Wari tie-dye styles date 600-900 CE (Rowe 2012: 200-201). At least some textiles discussed here could have been produced during the first part of the Middle Horizon, but the time period when they were placed on the southern platform of the Huaca del Sol remains unclear.7

As highland Cajamarca ceramic styles were discovered together with Moche, Wari, and other ceramics on the Huaca del Sol, what was the nature of highland interaction at the Huacas de Moche? Shinya Watanabe (2019) identifies Wari connections with Cajamarca throughout the Middle Horizon. George Lau (2012: 23, 30) suggests Wari and local Recuay leaders united within “religion and prestige economies” connected to “mummy bundles, portable huacas, marked adobes, trophy heads, even laborers” as well as Cajamarca ceramics, spondylus shells, greenstone objects, obsidian, ceramic figurines, and probably textiles. Textiles are rarely preserved in the highlands, and although Early Intermediate Period Recuay textiles have been discovered on the coast (Oakland Rodman and Cassman 1995), highland Middle Horizon textile styles are not well known. Cajamarca ceramics on the Huaca del Sol do identify association with late Moche culture at Moche and warp-faced textiles woven with cotton wefts in the Uhle textile collection could represent highland migrants together with local people buried on the southern platform. The cotton and camelid fibers mixed in these Middle Horizon warp-faced textiles represent an unusual feature at the Huacas de Moche. Cotton was spun in the S direction, but camelid fiber was always spun in the highland Z2S manner during late Moche periods. These camelid yarns could have been imported from the highlands as identified with isotope analyses for earlier yarn exchange in the Virú valley and in later Chancay yarns on the central coast (Szpak et al. 2015). Or highland spinners may have been present to spin imported or local camelid fiber at Moche. Late Moche people continued to spin cotton in their traditional method, but they may have begun spinning camelid fiber in the opposite direction with vertically held spindles as Vreeland (1986: 370-371) describes for highland migrants to the chaupiyunga or “half-coast.” Because it is not necessary to use whorls for Moche-style horizontal spinning, the clay spindle whorls discovered at the Huacas de Moche in late Moche contexts (Millaire 2008) and produced in the late Moche urban workshop (Bernier 2010) suggest that whorls were either added to the horizontal spindle for cotton or that drop-spindles may have been adopted for spinning camelid fiber in late Moche period at Moche.

What does Wari have to do with the Huaca del Sol?

In a recent study, Jeffrey Quilter examined changes in Moche ceramic forms toward probable Moche and Wari relations finding strong evidence in ceramics associated with feasting and the use of small copitas in northern Moche centers that ultimately derive from earlier use at Wari with the same form and use (Quilter 2020a, 2020b) . Edward Swenson (2012: 97-98) described cosmological co-existence within northern late Moche with Wari and Cajamarca highland influence in the use of masculine chicha-drinking rituals and feasting at the same time as the rise of the coastal, Moche cult of the female priestess or Sacerdotisa; an explanation for continued Moche religion, albeit in an altered Wari world. The copita form has not been excavated in southern Moche contexts, however, Tufinio’s new excavations identify feasting on the western side of the southern platform of the Huaca del Sol and rituals and burials as Uhle discovered on the east side. Santiago Uceda (2010: 199-200) discussed the political context of late Moche at the Huacas de Moche as a “society in crisis” and wondered how a construction as monumental as the Huaca del Sol could have been accomplished. He noted that the brick type, form of the huaca, and the massive building project with its control of tribute and labor suggested northern Moche and Lambayeque traits at the Huacas de Moche. He also considered that foreign influence from Wari or Pachacamac and pressure from Cajamarca or Huamachuco might all have been involved. Archaeologists working in regions bordering southern Moche in the Culebras and Huarmey Valleys see the strongest evidence for Wari interference and conquest during the late Moche period that explains Moche site abandonment and population movement as a response to direct Wari control (Giersz and Makowski 2014; Giersz et al. 2014). Justin Jennings (2006: 277-278; 2010) considered that Wari could have worked with local elites in the exchange of specialty items valued for their exotic qualities and ritual significance with “no coercive or redistributive mechanisms”. But in a later article considering “if a Wari Empire existed,” Timothy Earle and Jennings have proposed much stronger Wari control of elaborate textiles and decorated pottery as a probable foundation for wealth finance and the principal way that Wari could have interacted with local elites (Earle and Jennings 2012: 216-220). By controlling raw material, “high-end commodities,” and perhaps even “capturing gifted specialists”, they could establish the network for distribution of these coveted objects “that represented status and carried the state-sponsored ideology.” This article did not intend to address Wari as an empire, the original goal was an attempt to understand where and when elegant and vibrant Moche-Wari textiles could have been produced.8 Moche weavers were active during late Moche in the production of magnificent cotton and alpaca textiles and the large quantity of brilliant alpaca yarns suggests that raw materials, perhaps yarns already spun and dyed, were imported into Moche centers where Moche specialists wove panels of different textile structures to be assembled into garments. Some Moche-Wari textiles were woven with Wari imagery, like the small tapestry that Uhle excavated at Moche, and other Moche textiles were exported outside of Moche where they have been discovered in Middle Horizon burial contexts.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Photo by Amy Oakland.

Before and after Max Uhle excavated at Moche, he collected well-preserved textiles at Pachacamac and Chimu Capac in the Supe Valley, many woven with Moche-style S-spun cotton yarns (Oakland 2020a, Oakland 2020b). Huarmey Valley’s El Castillo textiles were woven with Moche S-spun cotton yarns and in each of these sites coastal, highland, and Wari textiles were also present. Prümers (1990, 2001) discovered twenty different examples of iconic Wari weft-interlocked tapestries, like the yellow man’s tunic (Figure 7.14) from Castillo Tomb 1 (Prümers 1990: 21-24, Fig. 6E) and a red Wari tunic fragment (Figure 7.31) from Tomb 4 (Prümers 1990: 30-32, Fig. 10C), a textile similar to an almost complete Wari tunic at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C. (Berg and Jennings 2012: Fig. 15). Along with hundreds of Moche-Wari textiles found at El Castillo, Prümers also collected fragments of Moche face-neck jars, incised and modeled Casma styles, and a small sample of Wari ceramics, a combination specific to the Middle Horizon. Uhle excavated a similar mix of styles at Chimu Capac where he catalogued four Wari tapestry tunics as well as central coast and highland shirt styles together with the complete Moche-Wari sleeved shirt 4-7827 (Figures 7.20, 7.32). Lila O’Neale (1933) was the first to discuss this shirt as a remarkable example of combined weaving patterns and techniques woven in twelve separate panels that included “patchwork” or discontinuous warp and weft technique, reinforced tapestry, and Moche-Wari slit-tapestry borders.9 The shirt was woven by Moche weavers with S-spun cotton yarns paired in the warp and used as singles in the weft in the plain weave sections, S2Z cotton yarns in the warps of the slit-tapestry borders, and Z2S camelid fiber for the patterns that combine Wari figures with Moche cat images below. At Chimu Capac on the central coast, Uhle excavated a wide variety of brilliantly dyed Moche weavings in slit-tapestry technique with S-spun cotton warp yarns, some with Wari style staff-bearing figures (Figure 7.33) and others with Moche catfish designs within a diamond grid (Figure 7.34). Moche weavers also created sleeved-shirts in double cloth technique with red camelid fiber and white S-spun cotton woven in the Moche technique that adds discontinuous-weft color spots, some with feline motifs (Figure 7.35) and other sleeved shirts with images of snakes and rays (Figure 7.36). Moche weavers created slit-tapestry openwork bands like the type that Uhle collected on the Huaca del Sol. The garments could have been produced specifically for burials (Millaire 2008) or perhaps this highly decorative clothing style is represented in Moche V and late Moche Fineline ceramic paintings as the patterned tunics worn by late Moche men. The Moche IV ceramic that Bernier (2010: Fig. 8) illustrates from the late Moche workshop depicts a Moche man holding a sleeved-shirt in front of himself, as if presenting the finished object. Were the Huacas de Moche involved in the exchange of textiles with Wari or with other coastal groups? Moche textiles have been discovered in regions far from Moche and surely more will be identified in Ancon and Pachacamac and other large Middle Horizon coastal cemeteries when investigators notice the Moche tradition of S-spun cotton yarns, as Mary Frame and Rommel Ángeles (2014) have in Middle Horizon burials at Huaca Malena in the Asia Valley of Perú’s south coast. At the Huacas de Moche, weavers must have been involved in the production of Moche-Wari textiles during the late Moche period, some with Wari imagery like the small slit-tapestry that Uhle excavated on the Huaca del Sol. According to Uceda (2010; Uceda et al. 2016), following the abandonment of the Huaca de la Luna, Moche inhabitants remained at the Huacas de Moche for at least 150 years. This late urban group is responsible for the expansion of the Huaca del Sol and the construction of the New Temple with murals depicting Moche weavers (Trever 2016) and the famous “Revolt of the Objects” where spinning tools and weavings hold Moche warriors by the hair.10 Clearly weaving figured prominently during this period at the Huacas de Moche.

This study presents Uhle’s Huaca del Sol Südplateau textile sample as evidence for the existence of multiple and synchronous forms and styles of textile production occurring at the Huacas de Moche, including distinct Moche and Wari textiles, hybrid Moche-Wari textiles, and Middle Horizon ceramic styles. Although the collection is small, Uhle excavated this same stylistic mixture in larger Middle Horizon cemetery collections along the Peruvian coast. Future analyses on the most recent excavations at the Huaca del Sol will help to understand more precisely when Moche and Wari relations occurred at the Huacas de Moche and when Moche-Wari textiles were woven and placed by Moche people on the Huaca del Sol.

Notes

1. Uhle (1913: Figure 3) marked this area as C and called the east side the Südplateau or southern platform on his plan of the Huaca del Sol. Kroeber (1925) and Menzel (1977) called these Huaca del Sol excavations Site A. This same area is now called Unidad 1 de Sección 4 at the Huacas de Moche (Tufinio et al. 2014).

2. Extensive scholarship exists on the Moche cotton tradition; see Bennett and Bird 1964; Conklin 1979; Donnan and Donnan 1997: 215; Fernández 2008; Jimenez Diaz 2002; Millaire 2008; O’Neale 1946, 1947; O’Neale and Kroeber 1930; Prümers 1990, 1995, 2007

3. Lila O’Neale (1946: 276, note 4) identified complex twill structures in Uhle’s Site F collection and stated: “Fortunately, a solution of the question of when the heddle appeared among people of Mochica culture does not depend upon a piece of ceramic evidence” countering Thomas A. Joyce’s (1921) description that the vase painting depicted only simple weaving. She noted that the vase was discovered in “a Chicama valley grave” illustrated by Means (1931: Fig. 2) and Montell (1929). For more recent discussions of Moche production weaving and the Weaver Vase see Gayoso Rullier (2007), Millaire (2008), and Shimada (2001).

4. Uhle’s unpublished book-length Moche report, written in German, was translated into Spanish by Peter Kaulicke (2014). Rafael Valdez (1998) translated Uhle’s 1913 Die Ruinen von Moche “del alemán al español” in Kaulicke, editor (1998). For this paper I am using Uhle’s 1913 Die Ruinen von Moche translated from German to English by Pedro Bandolero.

5. The same combination of Wari tie-dye, Wari tapestry tunic, and coastal slit-tapestry was found together burned, under a newly prepared mummy bundle placed over the abandoned Huaca Cao in the Chicama Valley (Oakland Rodman and Fernandez 2001: Figs. 30-33). The Huaca Cao was abandoned at the same time as the Huaca de la Luna at Moche.

6. Flannery Surette (2015: 74, Figure 21, 117-118) illustrates and discusses another blue and white cotton, early Moche/Gallinazo textile from the Virú Valley at Huaca Gallinazo (PAV20 a) that is woven with paired white S-spun cotton warp and weft with paired blue S-spun cotton supplementary-wefts to create images of catfish heads and crosses within a diamond grid very similar to the later Huacas de Moche textiles discussed in this paper.

7. Recently, Shinya Watanabe (2019:239) determined from Uhle’s (1913[1998]2014) drawings that the Cajamarca ceramics from the Huaca del Sol date to Cajamarca Medio C (850-950 CE), however new excavations completed on the Huaca del Sol (Tufinio et al. 2014) illustrate various Cajamarca styles. The textile portion of Tufinio’s Huaca del Sol excavations are currently being analyzed by Lizbeth Pariona Muñoz (n.d. 2021). Giersz and Makowski (2014) have published new estimates for absolute Middle Horizon dating that suggest a period 100-200 years later than the dates originally suggested by Menzel. Other Moche chronologies have also suggested later Middle Horizon dates (Aimi et al. 2016).

8. Uhle (1903: 26) “for want of a better term” chose “epigonal” to describe a style that, “although closely related to the style of Tiahuanaco, is inferior to its famous prototype in almost every respect.” The epigonal textiles that Uhle excavated at Pachacamac and Chimu Capac include Moche-Wari examples and other coastal-Wari styles woven in Z2S-spun cotton and camelid-fiber that identify their central and south coast origins. The term misrepresents the immense artistic skill and innovative combination of materials and techniques created by coastal weavers during this period.

9. Dorothy Menzel (1977) illustrated and discussed the Chimu Capac sleeved-shirt and William Isbell and Margaret Young-Sanchez (2012) illustrated the shirt in color as an example of late Wari style. Ann Rowe (1977, 2012) has described the Wari-associated tie-dye and the structure of discontinuous warp and weft and Jane Rehl (2006) has discussed the construction and distribution of this iconic Peruvian technique. Helen Engelstad (1986) named the particular technique “reinforced tapestry”: a type of brocading within a plain weave textile. Englestad’s examples were all from Pachacamac and the central coast woven with Z2S cotton and camelid fiber.

10. The Huacas de Moche “Revolt of the Objects” mural has been illustrated as a drawing (Kroeber 1930: Frontispiece; Quilter 1990, Figure 2) and recently in a color version (Uceda et al. 2016: 198-199). The life-size mural appears to represent objects specific to spinning and weaving and to the Moche priestess. The largest, central objects include the priestess headdress and beads with neck ties and attached cloth bands as noted in drawings such as the Presentation Theme (Quilter 1990: Figure 6) or in ceramic figurines (Donnan and Donnan 1997: Figure 19). The priestess’s beads and headdress attributes are animated with arms and legs and they hold or threaten Moche warriors. Two other animated objects, a Moche textile panel patterned in diamond grid and dots with a small shield and a tall oval image that probably represents a copa, the roll of prepared cotton fiber for spinning (Vreeland 1986) both hold warriors by the hair. The right side of the mural illustrates three men, two dressed in spotted tunics holding ropes connected to naked prisoners and the other with a vertically striped tunic holds the stemmed cup associated with the priestess. Two non-animated spindles begin the sequence on the left and a “nonanimated tripod”, (Quilter 1990: 47, Figure 2)) not pictured in the new Uceda et al. drawing, could represent the three-legged Moche spinner’s stand or kaite next to an animated narrow band, perhaps a weaver’s backstrap belt.

Acknowledgements

This paper has been developed from my presentation in January 2020 at the Institute of Andean Studies 60th annual meeting at the University of California, Berkeley. I thank Alicia Mattera for the map in Figure 1. In February 2020 I visited the Huacas de Moche and was fortunate to meet archaeologists Moisés Tufinio, Enrique Zavaleta, and Lizbeth Pariona Muñoz and to examine textiles recently excavated on the south platform/ Sección 4 of the Huaca del Sol, that are the topic of a thesis by Pariona Muñoz. Archaeologist Ceyra Pasapera introduced me to Victoria Inoñaú at Sipán. In Cusco I met Florintina Huaman at the Centro de Textiles and I thank both Victoria and Florintina for allowing me to photograph their spinning techniques. In Lima I enjoyed conversations with Peter Kaulicke, Sonia Guillen, and Carmen Thays Delgado at the Museo Nacional de Arqueologia, Antropologia y Historia where I photographed textiles from Heiko Prümers’ collection from El Castillo in the Huarmey Valley. Thank you, MNAAH and Heiko for allowing me to photograph and publish these Moche textiles. I appreciate my discussions about early Moche and Gallinazo textiles with Arabel Fernandez and Flannery Surette. And thank you very much Clark Erickson, Anne Tiballi and Penn Museum for allowing me to publish the textile fragments that Max Uhle collected in Pachacamac and compared with those he found in Moche. Michele Koons, Heiko Prümers, Peter Kaulicke, and George Lau gave valuable suggestions during the course of writing this essay. The paper benefited in focus through comments made by Jeffrey Quilter, the reviewer of this volume, however I alone am responsible for the final content. I analyzed Uhle’s Moche textile collection a long time ago in the Lowie Museum and am grateful to James Farmer and Rex Koontz for this opportunity to publish the Moche group with the courtesy of the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley.

Works Cited

Aimi, Antonio, et al.

2016 “Hacia una Nueva Cronología de Sipán”. In Lambayeque Nuevos Horizontes de la Arqueología Peruana, Antonio Aimi, Krzysztof Makowski and Emilia Perassi, eds., pp. 129-156. Milan: Ledizioni.

Bennett, Wendell C. and Junius B. Bird

1964 Andean Culture History. Second and Revised Edition. Published for the American Museum of Natural History. Garden City, New York: Natural History Press.

Berg, Susan E. and Justin Jennings

2012 “The History of Inquiry into the Wari and Their Arts”. In Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes, Susan E. Berg, eds., pp. 5-27. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Bernier, Hélène

2010 “Craft Specialists at Moche”. Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 21, No. 1 (March)22-43.

Bernier, Hélène and Claude Chapdelaine

2018 “Interacting Polities on the North Coast of Peru: The Moche and Wari Dilemma”. In Images in Action, The Southern Iconographic Series, William Isbell, Mauricio Uribe, Anne Tiballi, and Edward Zegarra, eds., pp. 571-598. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, UCLA.

Castillo, Luis Jaime

2001 “La Presencia Wari en San José de Moro”, Huari y Tiwanaku: Modelos vs. Evidencias. Boletín de Arqueologia PUCP 4 (2000), Peter Kaulike and William Isbell, eds., pp. 143-180. Lima: Fondo Editorial PUCP.

2012 “Looking at the Wari Empire from the Outside In”. In Wari, Lords of the Ancient Andes, Susan Bergh, ed., pp. 47-64. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art and New York: Thames and Hudson.

Conklin, William

1979 “Moche Textile Structures”. In The Junius B. Bird Pre-Columbian Textile Conference, May 19th and 20th, 1973, Ann Pollard Rowe, et al. eds., pp. 165-184. Washington, D.C.: The Textile Museum and Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University.

Cruz, Gianella, et al.

2019 “Contextos Funerarios del Horizonte Medio (c. 600d.C.-900 d.C.) en el Complejo Arqueológico de Huacas del Sol y la Luna”. In Informe de Practices Pre-profesionales (Tesina). Trujillo: Escuela de Arqueología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Perú.

Donnan, Christopher

2011 “Moche Substyles: Keys to Understanding Moche Political Organization”, Boletín Del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 105-118. Santiago.

Donnan, Christopher and Sharon Donnan

1997 “Moche Textiles from Pacatnamu”. In Pacatnamu Papers Volume 2, The Moche Occupation, Christopher Donnan and Guillermo Cock, eds., pp. 215-242. Los Angeles: The Fowler Museum of Cultural History, and The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, UCLA.

Earle, Timothy and Justin Jennings

2012 “Remodeling the Political Economy of the Wari Empire”, Boletín de Arqueología PUCP, No. 16, pp. 209-226.

Engelstad, Helen

1986 “A Group of Grave Tablets and Shirt Fragments from Pachacamac”, Ñawpa Pacha 24:61-72. Berkeley: Institute of Andean Studies.

Fernández, Arabel

2008 “Notas sobre el testigo No. 3, Tumba 18, Plataforma Superior, Huaca de la Luna”. In Investigaciones en la Huaca de la Luna 2001, Santiago. Uceda, Elias Mujica, and Ricardo Morales, eds., pp. 261-267. Trujillo: Patronato Huacas del Valle de Moche and Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Frame, Mary and Rommel Ángeles Falcón

2014 “A Female Funerary Bundle from Huaca Malena”, Ñawpa Pacha 34(1):27-59. Berkeley: Institute of Andean Studies.

Gayoso Rullier, Henry Luis

2007 Tejiendo el Poder: Los Especialistas Textiles de Huacas del Sol y de la Luna. Tesis de Maestria, Sevilla: Universidad Pablo de Olavide.

Giersz, Milosz and Krysztof Makowski

2014 “The Wari Phenomenon: In the Tracks of a Pre-Hispanic Empire”. In Castillo de Huarmey. El Mausoleo Imperial Wari, Milosz Giersz and Cecilia Pardo, eds., pp. 285-294. Lima: Mali.

Giersz, Milosz, et al.

2014 “Las Fronteras Meridionales de Moche y Chimu”. In Contributions in New World Archaeology, New Series, vol. 6, Janusz Krysztof, et al., eds. Cracow: Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Grieder, Terence

1975 “The Interpretation of Ancient Symbols.” American Anthropologist 77 (4): 849–55.

Grieder, Terence, et al.

1988 La Galgada, A Preceramic Culture in Transition. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Isbell, William and Margaret Young-Sanchez

2012 “Wari’s Andean Legacy”. In Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes, Susan Bergh, ed.,251-266. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art and New York: Thames and Hudson.

Jennings, Justin

2006 “Understanding Middle Horizon Peru”, Latin American Antiquity 17(3) 265-285.

Jimenez Diaz, Maria Jesus

2002 “The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us about Northern Textile Production?”. In Silk Roads, Other Roads: Textile Society of America 8th Biennial Symposium, Sept. 26-28, 2002, Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College.

Joyce, Thomas A.

1921 “The Peruvian Loom in the Proto-Chimu Period”, Man, pp. 177-180.

Kaulicke, Peter

1998 “Releer a Uhle, Comentarios y Lecturas”. In Max Uhle y el Peru Antiguo, Peter Kaulicke, eds., pp. 179-203. Lima: Fondo Editoral, PUCP.

2014 Max Uhle: Las ruinas de Moche. Libro Electrónico. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la PUCP.

Koons, Michele

2015 “Moche Sociopolitical Dynamics and the Role of Licapa II, Chicama Valley, Peru”, Latin American Antiquity, Vol 26, No.4, pp. 473-492.

Koons, Michele and Bridget Alex

2014 “Revised Moche Chronology Based on Bayesian Models of Reliable Radiocarbon Dates”, Radiocarbon, Vol. 56, No. 3, pp. 1039-1055.

Kroeber, Alfred

1925 “The Uhle Pottery Collections from Moche”, University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 21(6) 191-264.

1930 “Archaeological Explorations in Peru, Part II: The Northern Coast”, Anthropological Memoirs Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 45-116. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Lau, George

2012 “Intercultural Relations in Northern Peru: The North Central Highlands During the Middle Horizon”, Boletín de Arqueología PUCP, No. 16, pp. 23-52, Lima.

Makowski, Krzysztof

2003 “La deidad suprema en la iconografía mochica: Como definirla?”. In Moche: Hacia el Final del Milenio, Santiago Uceda and Elias Mujica eds., pp. 343-381. Trujillo: Universidad de Trujillo and Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Means, Philip

1931 Ancient Civilizations of the Andes. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Menzel, Dorothy

1977 The Archaeology of Ancient Peru and the Work of Max Uhle. Berkeley: R. H. Lowie Museum of Anthropology, University of California Berkeley.

Millaire, Jean-François

2008 “Moche Textile Production on the Peruvian North Coast, A Contextual Analysis”. In Art and Archaeology of the Moche, An Ancient Andean Society of the Peruvian North Coast, Steve Bourget and Kimberly Jones, eds., pp. 229-245. Austin: University of Texas Press.

2009 “Woven Identities in the Virú Valley”. In Gallinazo, An Early cultural Tradition on the Peruvian North Coast, Jean-François Millaire with Magali Morlion, eds., pp. 149-166. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California.

Montell, Gösta

1929 Dress and Ornaments in Ancient Peru: Archaeological and Historical Studies. Goteborg: Elanders Boktryckeri Aktiebol AG.

Oakland, Amy

2020a “Middle Horizon Textiles from Chimu Capac, Supe Valley, Peru”. In PreColumbian Textile Conference VIII/ Jornadas de Textiles PreColombinos VIII (2019), Lena Bjerregaard and Ann Peters eds., (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2020). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/

2020b “Max Uhle’s Field Notes and Textile Collections from Chimu Capac, Supe Valley, Peru; Style and Cultural Affiliation During the Early and Late Middle Horizon”, Nawpa Pacha, Vol. 40, Issue 2. Lima: Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru.

Oakland Rodman, Amy and Viki Cassman

1995 “Andean Tapestry, Structure Informs the Surface”, Art Journal, Volume 54, Issue 2: Conservation and Art History pp. 33-39.

Oakland Rodman, Amy and Arabel Fernandez

2001 “Los Tejidos Huari y Tiwanaku: Comparaciones y Contextos”. In Huari Y Tiwaaku: Modelos vs. Evidencias, Primera Parte, Boletin de Arqueologia PUCP, No. 4 (2000), Peter Kaulicke and William H. Isbell, eds., pp. 119-130. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru.

O’Neale, Lila

1933 “A Peruvian Multicolored Patchwork”, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Jan.-Mar.) pp. 87-94.

1946 “Mochica (Early Chimú) and Other Peruvian Twill Fabrics”, Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 2:269-294.

1947 “A Note on Certain Mochica (Early Chimú) Textiles”, American Antiquity 12:239-245.

O’Neale, Lila and Alfred Kroeber

1930 “Textile Periods in Ancient Peru”. In University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 28, pp. 23-56.

Pariona Muñoz, Lizbeth

(n.d. 2021) Presencia Wari en el Valle de Moche?: El Estudio de los Textiles del Horizonte Medio en Huaca del Sol. Tesis de Licenciada en Arqueología, Trujillo, Spain: Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales.

Prümers, Heiko

1990 Der Fundort “El Castillo” in Huarmeytal, Peru. Einbertrag Zum Problem Des Moche-Huari Textilstils. 2 vols.. In Mundus Reihe Alt-Amerikanistik, Band 4, 2. Bonn: Holos Verlag.

1995 “Ein Ungewöhnliches Moche-Gwebe aus dem Grab des “Fursten Von Sipan” (Lambayeque-Tal, Nordperu) /Un Tejido Moche Exceptional de la Tumba Del Señor de Sipán”. In Beitrage zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Arquaologie, 15, 309-369. Mainz: Komission für Allgemeine und Verleichende Archäologie,

2001 “El Castillo” de Huarmey: Una Plataforma Funeria del Horizonte Medio”. In Huari y Tiwaaku: Modelos vs. Evidencias, Primera Parte, Boletin de Arqueologia PUCP, No. 4 (2000), Peter Kaulicke and William H. Isbell, eds., pp. 289-312. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru.

2007 “Los Textiles de la Tumba del “Senor de Sipan”, Zeitschrift fur Archaologie Au Bereuropaischer Kulturen 2:255-324.

Quilter, Jeffrey

1990 “The Moche Revolt of the Objects”, Latin American Antiquity, Vol.1, No. 1,42-65.

2020a “Moche Pottery: Forms, Functions, and Social Change”, Ñawpa Pacha, pp.1-23. Berkeley: Institute of Andean Studies.

2020b “Moche Mortuary Pottery and Culture Change”, Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 1-20.

Quilter, Jeffrey and Michele L. Koons

2012 “The Fall of the Moche: A Critique of Claims for South America’s First State”, Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 127-143.

Rehl, Jane

2006 “Weaving Principles for Life: Discontinuous Warp and Weft Textiles of Ancient Peru”. In Andean Textile Traditions, Papers from the 2001 Mayer Center Symposium at the Denver Art Museum, Margaret Young-Sánchez and Fronia W. Simpson, eds., pp. 13-42. Denver: Denver Art Museum.

Rowe, Ann Pollard

1977 Warp-Patterned Weaves of the Andes. Washington D.C.: The Textile Museum.

1984 Costumes and Featherwork of the Lords of Chimor. Washington D.C.: The Textile Museum.

2012 “Tie-Dyed Tunics”. In Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes, Susan E. Berg, ed., pp. 193-206. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Rowe, John

1954 Max Uhle, 1856-1944, A Memoir of the Father of Peruvian Archaeology. University of California Publications in American Archaeology, and Ethnology, Vol. 46, No. 1. Berkeley and Los Angeles.

1998 “Max Uhle y La Idea del Tiempo en la Arqueología Americana”. In Max Uhle y el Peru Antiguo, Peter Kaulicke, ed., pp. 5-21. Lima: Fondo Editoral, PUCP.

Scullin, Dianne and Brian Boyd

2014 “Whistles in the Wind: The Noisy Moche City”, World Archaeology, 46:3, 362-379.

Shimada, Izumi

2001 “Late Moche Urban Craft Production: A First Approximation”. In Moche Art and Archaeology in Ancient Peru, Joanne Pillsbury, ed., pp. 177-206. Studies in the History of Art 63. Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers, XL, National Gallery of Art of Washington. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Surette, Flannery

2015 Virú and Moche Textiles on the North Coast of Peru during the Early Intermediate Period: Material Culture, Domestic Traditions and Elite Fashions. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2829. Ontario: Western University.

Szpak, Paul, et al.

2015 “Origins of Prehispanic Camelid Wool Textiles from the North and Central Coasts of Peru Traced by Carbon and Nitrogen Isotopic Analyses”, Current Anthropology 56 (3):449-459.

Swenson, Edward

2012 “Los Fundamentos Cosmológicos de las Interacciones Moche-Sierra Durante el Horizonte Medio en Jequetepeque”, Boletín de Arqueología PUCP, No. 16:79-104.

Trever, Lisa

2016 “The Artistry of Moche Mural Painting and the Ephemerality of Monuments”. In Making Value, Making Meaning: Techné in the Pre-Columbian World, Cathy Lynne Costin, ed., pp. 253-280. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Trustees of Harvard University.

Tufinio, Moisés, et al.

2012 “Excavaciones en la Sección 2 de Huaca del Sol”. In Informe Técnico 2011 del Proyecto Arqueológico Huaca de la Luna, Santiago Uceda and Ricardo Morales, eds., pp. 241-305. Trujillo, Perú.

2014 “Excavaciones en la Sección 4 de Huaca del Sol”. In Informe Técnico 2013 del Proyecto Arqueológico Huaca de la Luna, Santiago Uceda and Ricardo Morales, eds., pp. 87-170. Trujillo, Perú: Ubbelohde-Doering, Heinrich.

Ubbelohde-Doering, Heinrich

1967 On the Royal Highways of the Inca, Civilizations of Ancient Peru. London: Thames and Hudson.

Uceda, Santiago

2008 “En Busca de los Palacios de los Reyes de Moche”. In Señores de los Reinos de la Luna, Krzysztof Makowski, ed., pp. 111-127. Lima: Banco de Crédito del Perú.

2010 “Huacas del Sol y de la Luna: Cien Años Después de los Trabajos de Max Uhle”. In Max Uhle: Evaluaciones de Sus Investigaciones y Obras, Peter Kaulicke, et al., eds., pp. 175-204. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru.

Uceda, Santiago, et al.

2016 Huaca de la Luna: Templos y Dioses Moches/ Moche Temples and Gods. Lima, Perú : WM, World Monuments Fund Perú: BACKUS Fundación.

Uhle, Max

1903 Pachacamac: Report of the William Pepper, M.D., LL.D., Peruvian Expedition of 1896. Philadelphia: Department of Archaeology, University of Pennsylvania.

1913 “Die Ruinen von Moche”, Société des Américanistes de Paris, Journal, n.s., 10, pp. 95-117.

Valdez, Rafael

1998 “Las Ruinas de Moche, Traducción del Alemán al Españo”. In Max Uhle y el Peru Antiguo, Peter Kaulicke, ed., pp. 205-227. Lima: Fondo Editoral, PUCP.

Vreeland, James

1986 “Cotton Spinning and Processing on the Peruvian North Coast”. In Junius B. Bird Conference on Andean Textiles, April 7 and 8, 1984, Ann P. Rowe, ed., pp. 363-383. Washington, D.C.: The Textile Museum.

Watanabe, Shinya

2019 “Dominio Provincial Wari en el Horizonte Medio: el Caso de la Sierra Norte del Perú”. In Research Papers of the Anthropological Institute, Vol. 8. Nagoya, Japan: Nanzan University.

Zavaleta, Luis Enrique, et al.

2013 “Excavaciones en El Sector Noroeste del Núcleo Urbano Moche: Contextos Funerarios y Su Relación con las Plataformas y La Plaza”. In Informe Técnico 2012 del Proyecto Arqueológico Huaca de la Luna. Santiago Uceda and Ricardo Morales, eds., pp. 263-362. Trujillo, Perú.

Zavaleta, Luis Enrique, et al.

2014 “Cambios Sociales y Políticos en el Moche Tardio y la Configuracíon de un Conjunto Administrative en el Núcleo Urbano del Complejo Arqueológico Huaca del Sol y Luna”. In Informe Técnico 2013 del Proyecto Arqueológico Huaca de la Luna. Santiago Uceda and Ricardo Morales, eds., 247-336. Trujillo, Perú.