8 The Disembodied Eye in Maya Art and Ritual Practice

Virginia E. Miller

https://doi.org/10.52713/ZADG2991

Enrolling out of curiosity in a graduate seminar in Pre-Columbian art as a first year MA student in Latin American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, I first met Terry Grieder in 1972. As would be expected during that era, George Kubler’s ideas were at the forefront of our lively class discussions, and we spent hours arguing the merits of disjunction vs. ethnographic analogy for interpreting ancient iconography. In fact, at that time there were few other art historians publishing on Pre-Columbian art, so we read a lot more anthropology and archaeology than art history. Although I eventually read Terry’s dissertation, which focused primarily on Maya form and style, at the time I don’t think I was aware that his was the first U.S. doctorate in Pre-Columbian art, nor that the field was so new.

Inspired by that seminar, I decided to continue my studies beyond the MA and complete a PhD, the second under Terry’s direction. By the time I knew him, he had moved away from his early work on the Maya and was deeply involved in Andean archaeology, while I chose to focus on Mesoamerica. Furthermore, he was always more interested in the study of style and technique than he was in iconography, which intrigued me the most. Nevertheless, he was a generous, supportive and at times challenging mentor who encouraged my efforts to understand the complexity of Classic Maya imagery as I struggled through the dissertation. Subsequently, I sent him all my publications and received reassuring and insightful commentaries in return. The following contribution is a testament to Terry’s intellect, guidance, and encouragement over many years.

Photo by Virginia E. Miller.

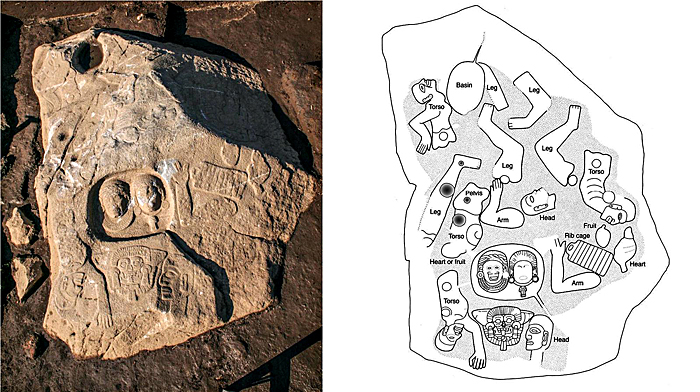

Mesoamerican iconography, archaeology, and ethnohistory all attest to the practice of removing and displaying a wide range of human body parts, either of revered ancestors or more frequently of humiliated captives (Chacon and Dye 2007). The best-known method of exhibiting a detached body part in Mesoamerica is the skull rack or tzompantli, which has its origins in the Preclassic period and culminates in the elaborately decorated platform of Chichén Itzá and later in the spectacular and massive displays of skulls at Tenochtitlan (Figure 8.1). The ritual use of digits, femurs, and other bony appendages is also well documented, as I have discussed elsewhere (Miller 2007). But with the exception of the heart, few sources address how organs and soft body tissues were curated during the brief time they could have been viable for manipulation or public viewing. Nevertheless, there is a rich corpus of Mesoamerican art that demonstrates that such exhibitions must have taken place. One vivid example is a recently discovered carved boulder in the Late Classic Cotzumalguapa style from Bilbao in Guatemala (Figure 8.2). Similar displays of body parts occur on Maya vessels depicting warriors and captives (www.mayavase.com: K1082, K6987).

Images courtesy of Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos (2014: figs. 9 and 11).

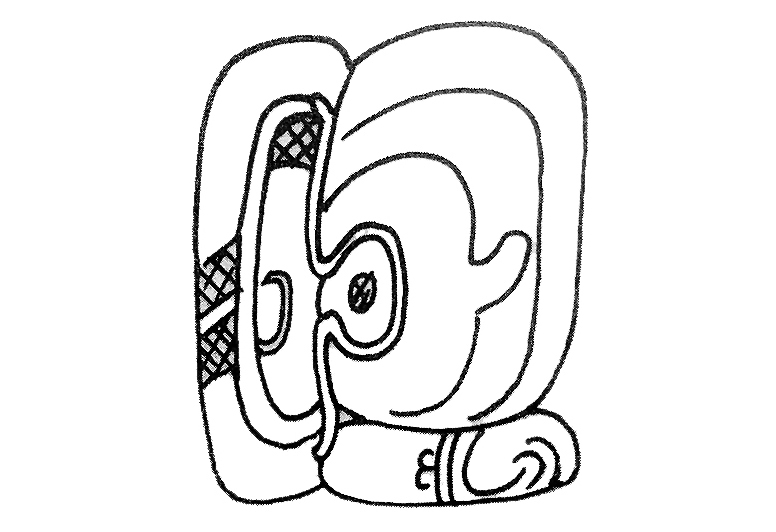

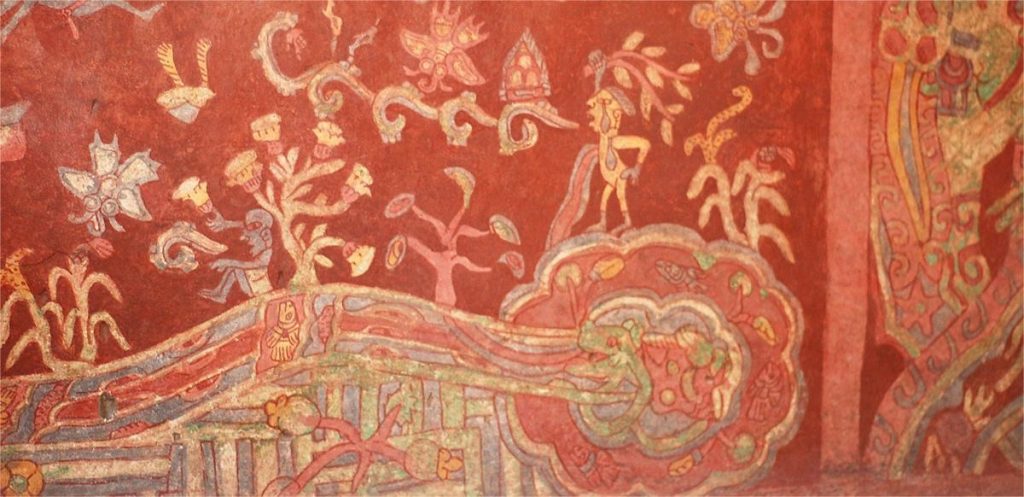

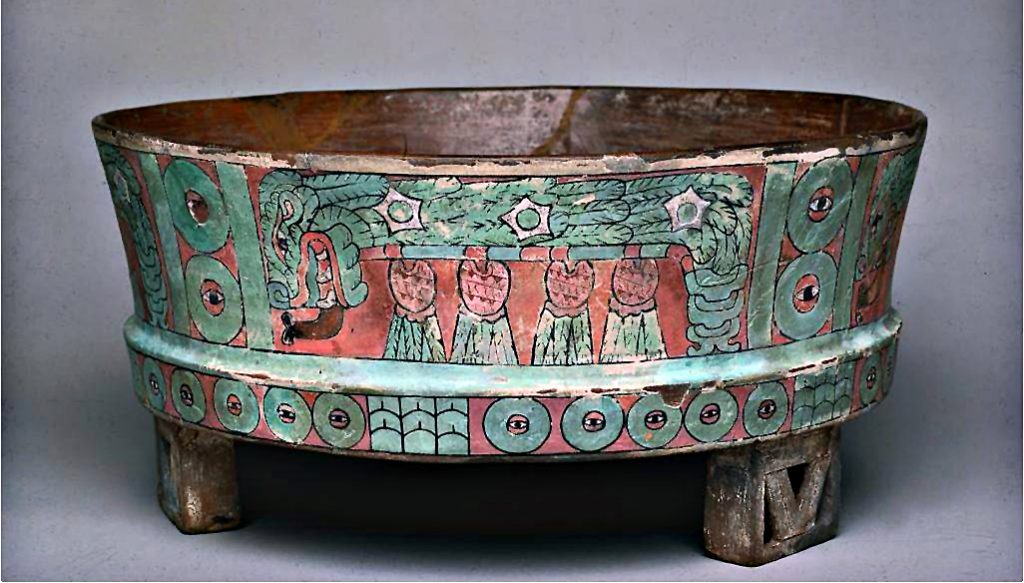

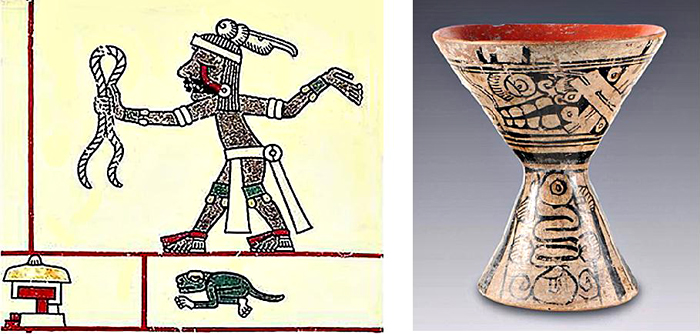

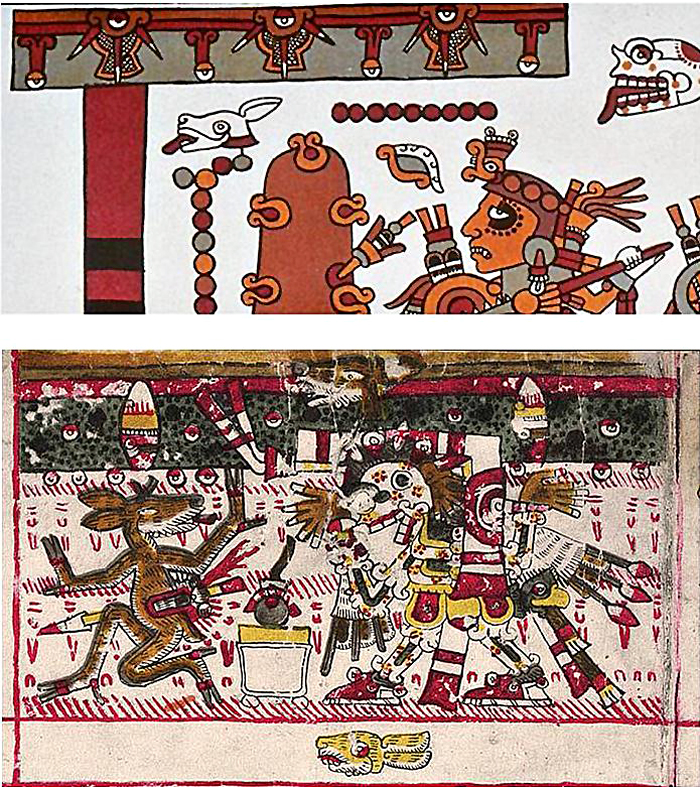

While skulls and bones are common motifs in Maya art and have been extensively analyzed, the pervasive imagery of eyeballs has not received the same attention. The detached eye appears in Mesoamerican art and writing from all periods, represented realistically or more frequently abstractly. Not surprisingly, the Classic Maya hieroglyph for “seeing”, read il or ila, depicts an eyeball in profile (Figure 8.3) (Houston et al. 2006: 172). Simplified or stylized versions of frontal eyes occur in a variety of contexts. They decorate streams of water in Teotihuacan murals, for example (Figure 8.4). The eyes may also be enclosed within jade disks, suggesting that they refer to something precious or shiny, or to superior vision (Figure 8.5). Extruded and detached eyeballs are represented in Postclassic highland Mexican art, appearing in murals, codices, and on ceramics (Boone and Collins 2013). They are usually represented as spheres with the cornea and/or pupil indicated and with the optic nerve, often unnaturally long, still attached (Figure 8.6:). Stylized eyes, usually with a distinctive red lid and presented frontally, are particularly prevalent in the Postclassic and sometimes stand in for stars in Central Mexican and Mixtec codices (Figure 8.7). Similar motifs, also representing heavenly bodies, appear earlier in painting and sculpture at Chichén Itzá and Tula (Miller 1989).

Used with the permission of Stephen Houston.

Photo courtesy of Claudia Brittenham.

Photo courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art, J.H. Wade Fund 1965.20.

Left: Codex Laud, page 23, detail of figure with extruded eye, courtesy of John Pohl.

Right: Late Postclassic polychrome cup from the Valley of Mexico depicting skull, crossed bones, and eye with optic nerve below.

Museo Amparo, Puebla, registry number 52 22 MA FA 57PJ 1438.

Upper: Detail, Nuttall Codex, page 75.

Lower: Detail, Borgia Codex, page 52.

In general, the eye motif is meant to signify radiating light (Garton and Taube 2017: 38). But when it is shown completely out of its orbit, either still attached to the head by the optic nerve, or as an independent object, the eye surely has a more ambiguous, if not outright sinister, connotation. Here, I will explore the various treatments and meanings of the detached human eyeball in Maya art, whether as a sacrificial offering, costume element, architectural and sculptural adornment, and symbol of both sight and loss of vision.

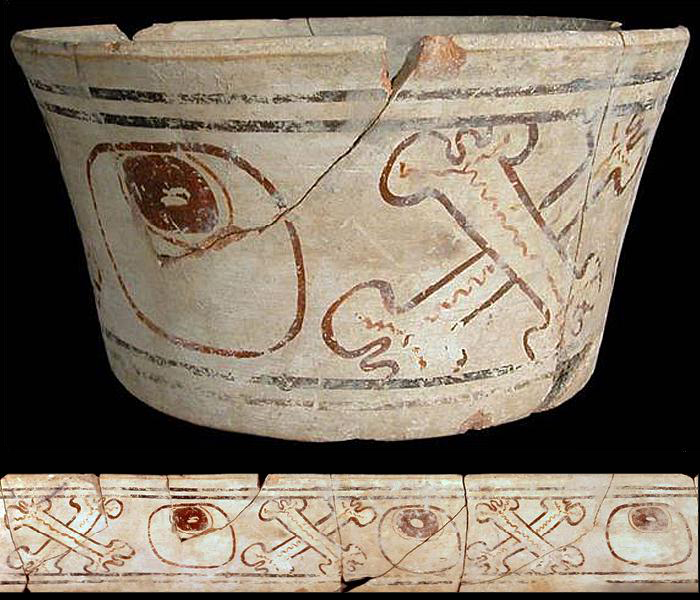

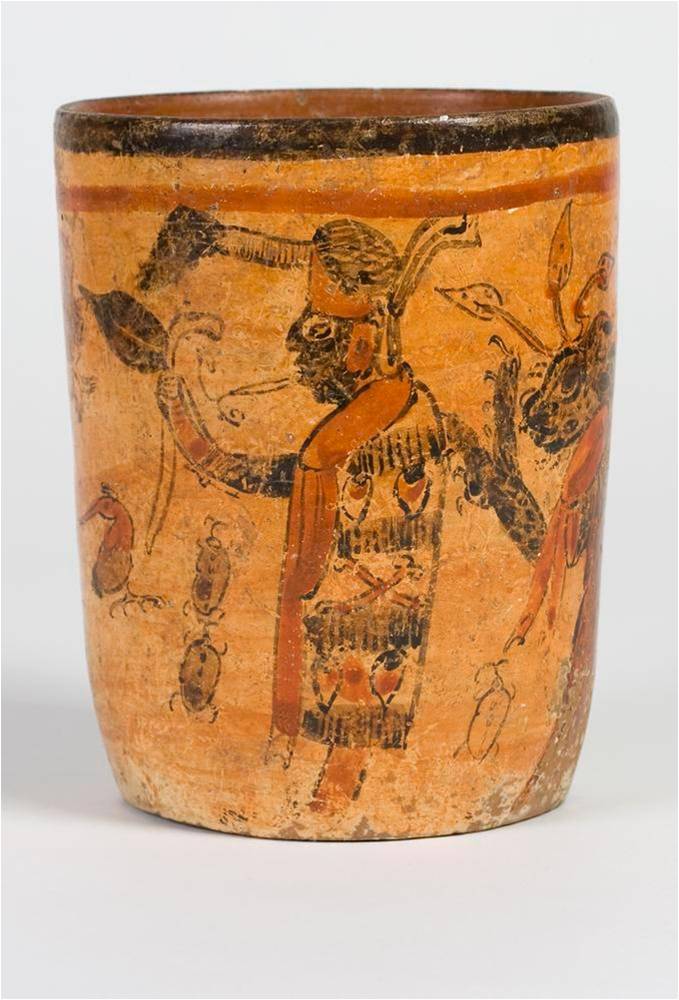

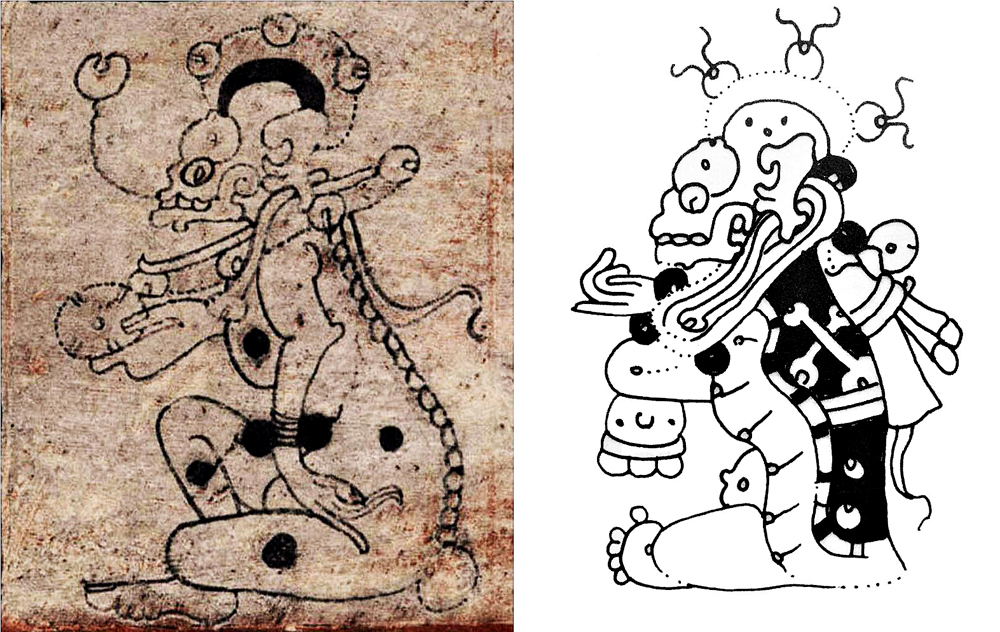

Eyeballs are a common motif on Classic Maya vessels, often combined with crossed bones (Figure 8.8). These grisly items are among the attributes of the wahyis, spirit beings combining human, zoomorphic, and skeletal attributes (Velásquez García 2015: 191). According to imagery on painted plates and pots, their food was particularly repellent, consisting of human body parts including femurs, hands, and eyes (Houston et al. 2006: 122-123, 221; Velásquez García 2015: 190). These three elements are often grouped together on plates being offered by denizens of the underworld (Figure 8.9). Humans and animals are shown with extruding eyeballs but appear still alive and active (Figure 8.10).1 Until the stalk is cut, the eye is still able to receive optical input (Houston et al. 2006: 166). Therefore, these figures should be understood not as blinded, but perhaps experiencing sight in an altered state (Hamann 2004: 84).

Upper: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala (Calvin n.d).

Lower: Rollout photograph.

Photos permission of Inga Calvin.

Photo by Justin Kerr, [K1181], Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

Photo by Justin Kerr, [K1743], Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

Of course, it is also possible that some images are meant to show eye detachment as a result of violent actions. In a recent article on ritual boxing in Mesoamerica, for example, two stone carvings of human faces are illustrated, one from highland Guatemala and the other in the Cotzumalguapa style, both with pendant eyeballs (Figure 8.11).2 The latter may depict the aged God N, a primordial Maya earth god (Taube and Zender 2009: 189-190). In any case, the authors suggest that blows to the head during a boxing event featuring stone weapons might cause eyes to pop out of their sockets.

Left: In the Cotzumalguapa style

Right: From highland Guatemala

Images from Taube and Zender 2009: 7.16 a and b. Published with the permission of the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press at UCLA.

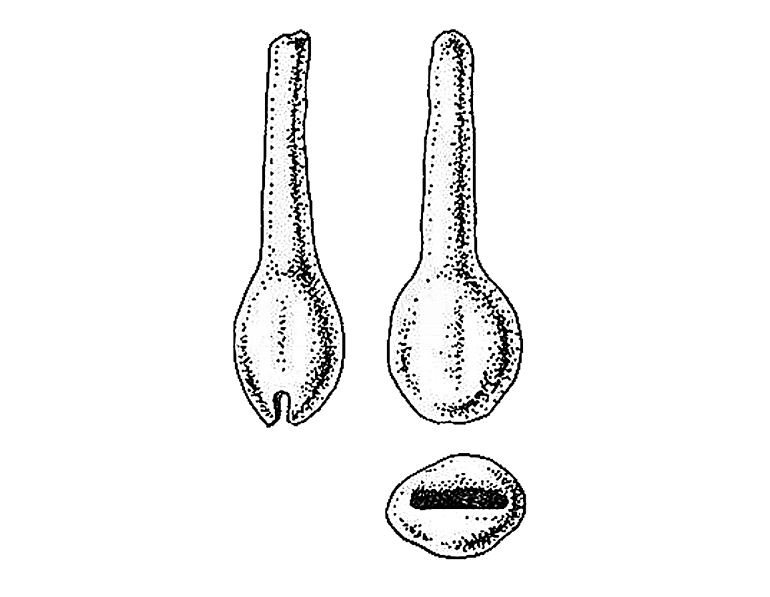

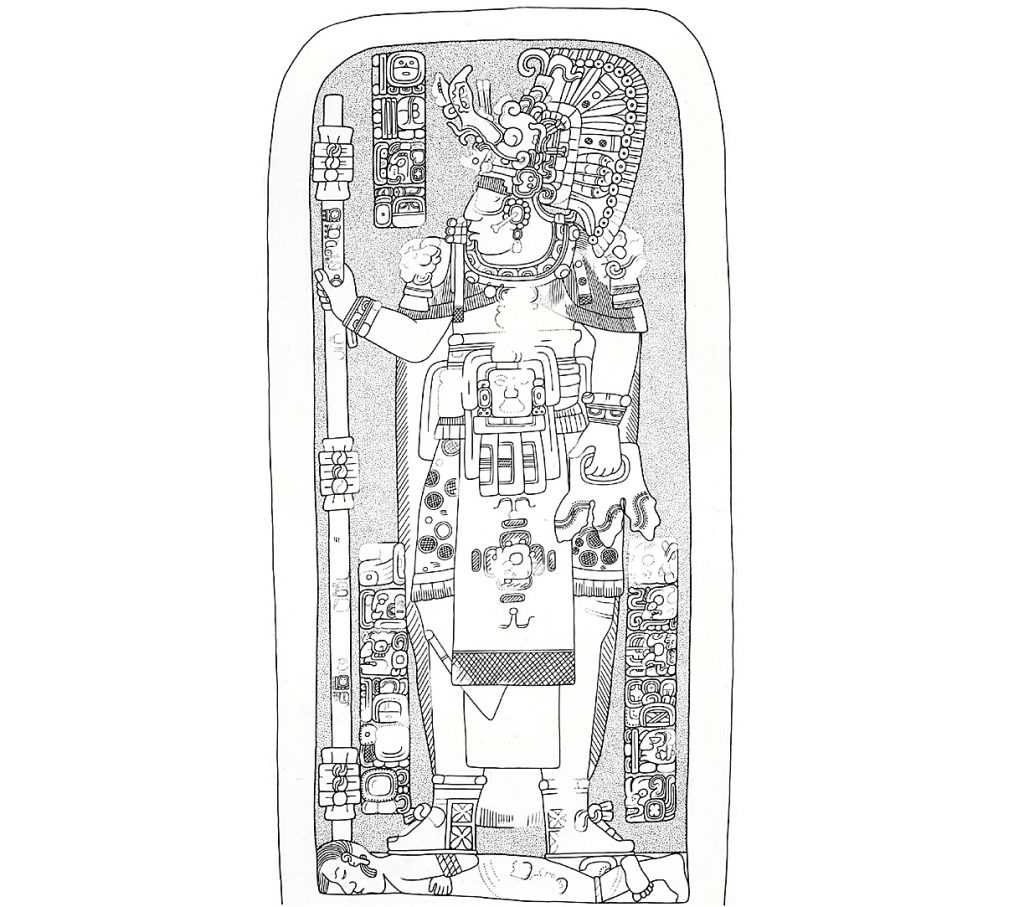

Animals, humans, and supernaturals, especially skeletal ones, are shown wearing a collar of detached eyeballs (Figures 8.10, 8.12). Many years ago, Jean-Jacques Rivard (1965) argued against the prevailing idea that such dangling objects, represented across Mesoamerica in various media, were copper bells. He identified them instead as eyeballs, and even suggested that a pair of clay objects excavated at Las Charcas in Guatemala were eyeball effigies forming part of a ritual costume (Figure 8.13) (Rivard 1965: 87). There is some evidence that he may have been correct. An unprovenienced, eroded column fragment now in a private collection in Mérida shows a standing lord wearing eyeballs around his waist (Figure 8.14) (Merk and Krempel 2017). The necklace worn by the ruler on Naranjo Stela 30 also appears to include pendant eyeballs (Figure 8.15).3 Given the prevalence of small, decapitated heads and skulls worn by Classic Maya rulers, there may be overlooked examples of pendant eyeballs, misunderstood as bells or shells.4 Whether body parts serving as accoutrements for the elite were real or “clever props” is less important than the fact that Mesoamericans chose to include them as part of their dress (Houston et al. 2006: 221).

Photo by Justin Kerr, [K0759], Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

Drawing after Rivard 1965: fig. 23.

Upper: Photos by Stephan Merk, digitally enhanced by Guido Krempel.

Lower: Preliminary drawing by Guido Krempel.

Images courtesy of Guido Krempel.

Crossed bones, skulls, and eyeballs form a cluster of elements that separately or in tandem adorn Mesoamerican clothing, architecture, and objects. A striking example can be seen in the battle scene covering the walls and vault of Room 2 at Bonampak, where trumpeters, festooned with human head necklaces, carry round objects with handles adorned with crossed bones and eyes.5 The same elements are painted on the trumpet of one of the musicians (Helmke 2020: fig. 5 c and d). Surely these sinister motifs, combined with the blare of martial music, were meant to intimidate the enemy during the attack pictured. Equally menacing were round shields edged with eyeballs, and sometimes covered with what appear to be flayed faces, carried by supernatural warriors represented on Maya vases (cf. Krempel 2015: figura XXIX-2-1; www.mayavase.com: K8201, K1873).

Both humans and deities, particularly aged ones, wear cloaks and skirts displaying various combinations of death motifs which may have been woven into cotton cloth or embroidered or painted on its surface (Figure 8.16) (Coltman 2018: fig. 10.2; Carter et al. 2020: fig. 2.6).6 Additionally, in images of skeletal wahyis on Classic Maya vases, eyeballs are often placed on top of crania, sometimes in tandem with a towering headwrap (Figure 8.17).7 Oddly, Classic Maya polychrome vessels sometimes feature deer covered in dark blankets decorated with bones and eyes. Although the deer was an important game animal for the Maya, its role in art and mythology is still not well understood. Nevertheless, the symbols on the blankets, as well the presence of deer remains in burials, hint at a close relationship between the animal and death in Maya ritual and belief (Graña-Behrens 2014: 5).8

Used by permission of the Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia.

Photo by Justin Kerr, [K8333], Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

A rare example of skeletal imagery on a monumental scale in the Late Classic period is seen in the well-known stucco frieze at Toniná. Among the various figures represented, a skeletal wahyis sports not only the requisite eyeball necklace and head ornament (not shown here), but also wears an eyeball pulled through his earlobe by the optic nerve in place of the conventional jade or cloth ear ornaments (Figure 8.18).9 Death deities represented in the Postclassic codices also wear the same sort of grisly earplug (Figure 8.19).

Drawing used with the permission of Karl Taube.

Left: page 15c (also note the death eye collar)

Right: page 12b (after Houston et al. 2006: fig. 4.28a), used with the permission of Stephen Houston.

Skulls and crossed bones are common architectural ornaments throughout Mesoamerica (cf. Miller 1999), but realistic eyeballs appear less frequently. Real eyes, or more likely effigies, may have once adorned buildings and monumental stone sculpture, however. One Maya vase, for example, depicts a cross-section of a structure whose surface is entirely covered with detached eyeballs (Figure 8.20). It is reminiscent of foliage-covered frameworks from which heads are hung, a form of skull rack also represented on Maya vases (Taube 2017: 32). Another vessel (www.mayavase.com: K718), although heavily damaged, shows a sacrificial victim reclining on a sacrificial altar marked with eyeballs and symbols for stone. Behind the altar rises a cloth-wrapped stela or speleotherm also painted or carved with floating eyeballs and other elements (Coltman 2021: 212, fig. 8.5a).

Photo by Justin Kerr, [K5538], Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

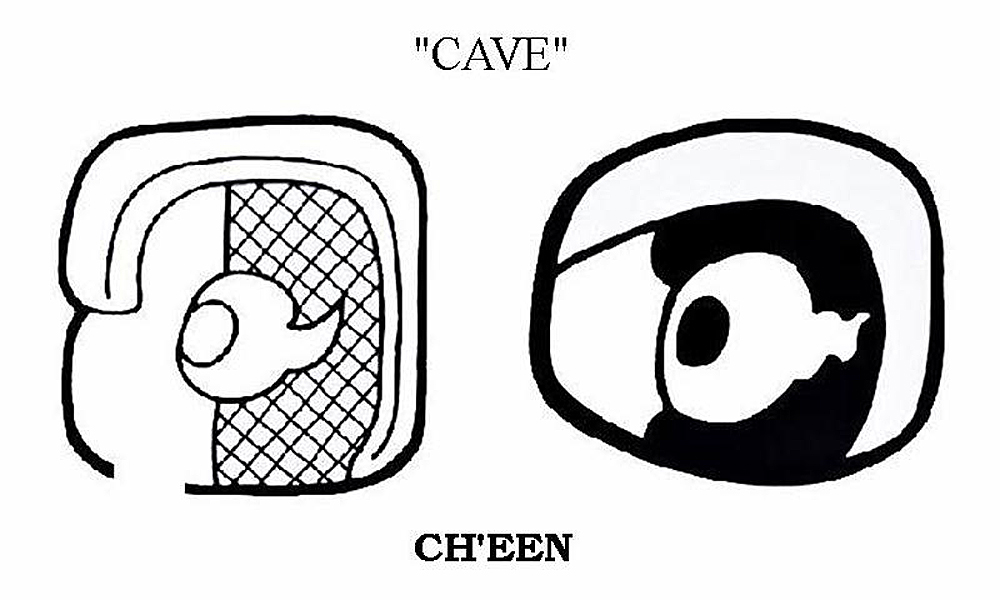

It should be noted that eyeball motifs may not always relate to dismemberment and death, but rather to aspects of sight or, alternatively, sightlessness (Brady and Coltman 2016). The eyeballs that decorate bats’ wings on Maya ceramics, for example, could refer to their ability to move around in complete darkness (Figure 8.21). Indeed, ch’een, the hieroglyph for “cave”, depicts a profile enclosure in which a disembodied eye floats on a black or cross-hatched background (Figure 8.22). Here, the eyeball would appear to simply signify complete darkness.

Photo by Justin Kerr, [K5224], Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

Drawing courtesy of Marc Zender (Stone and Zender 2011:133).

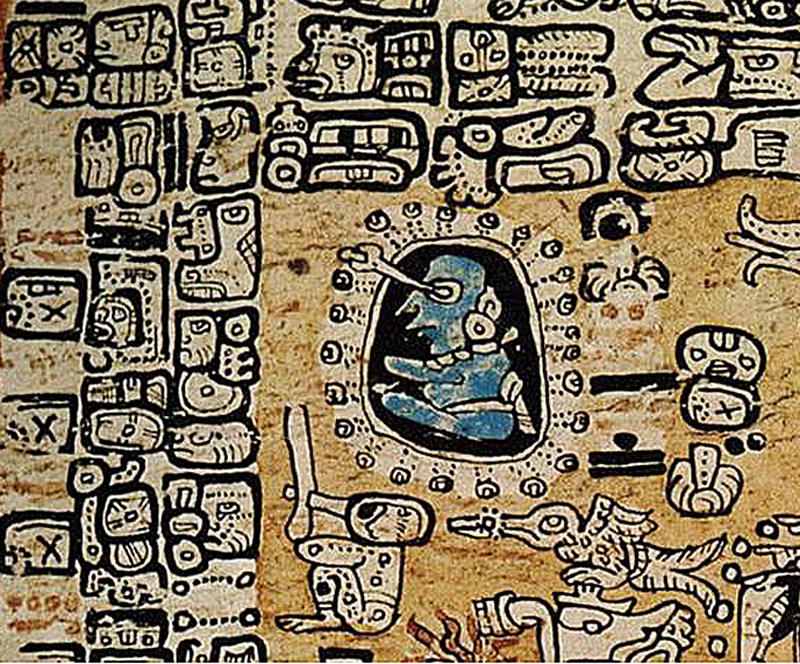

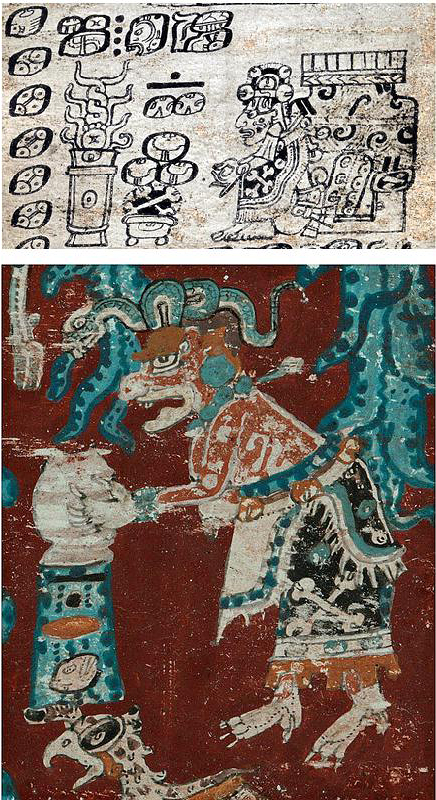

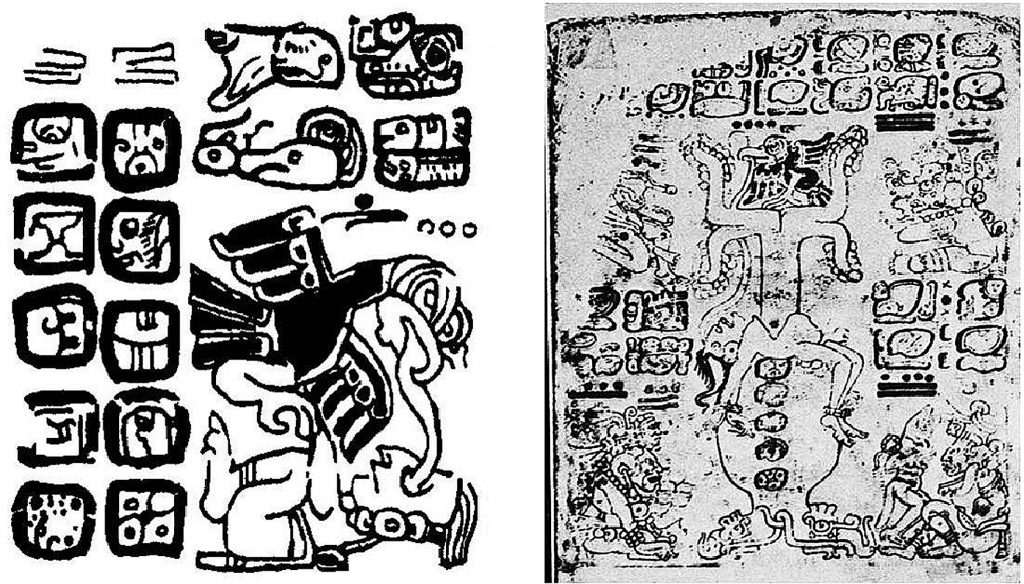

The eye might also refer to superior vision. In the Madrid Codex, for example, a seated astronomer with a protruding eye observes the eye-studded heavens (Figure 8.23) (Milbrath 1999: 251-253).10 A similar image occurs in the Central Mexican Codex Mendoza, c.1542, in which a disembodied eye is connected to the astronomer’s face by a dotted line, serving as “a kind of optical projectile” heading toward the eye-dotted sky above (Hamann 2018: 635, fig. 7). As Susan Milbrath (1999: 253) has suggested, death-eye collars may also represent stars, thereby connecting the night sky and the underworld. Clearly, while we may see disembodied eyes as purely macabre, ancient Mesoamericans may have viewed them differently depending on circumstances.

Image provided by Gabrielle Vail.

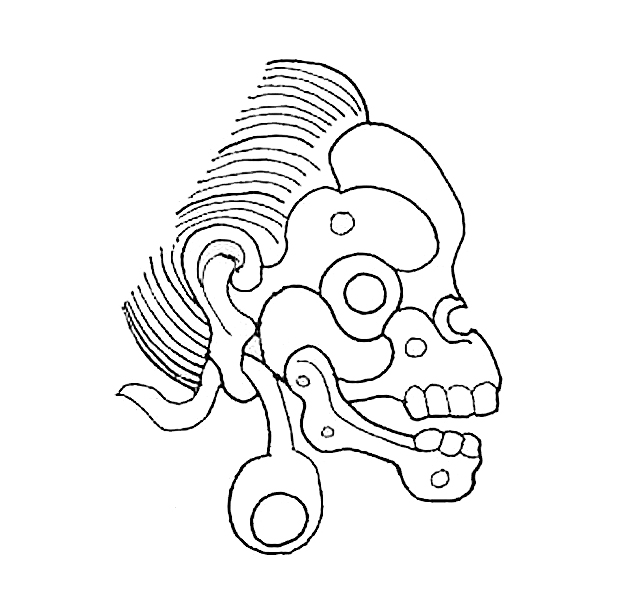

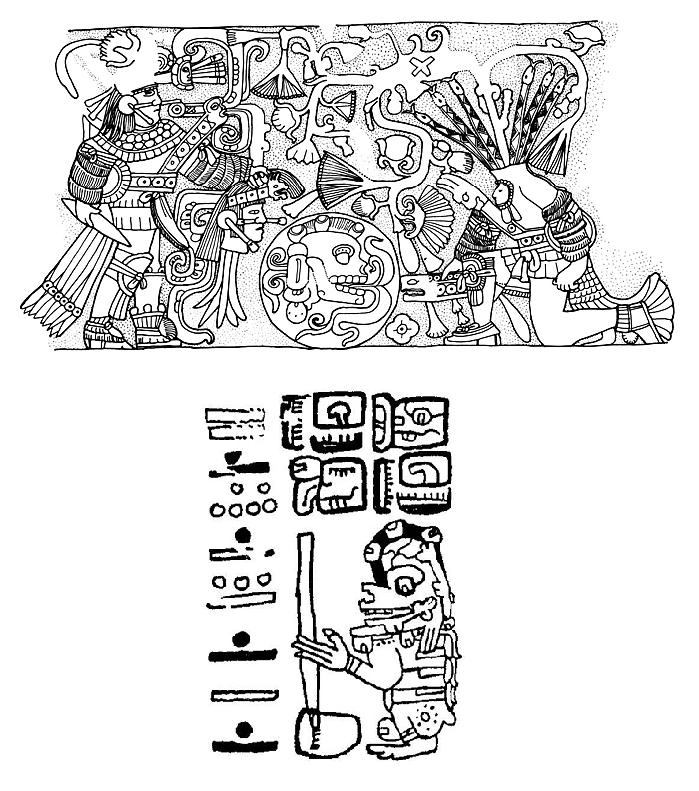

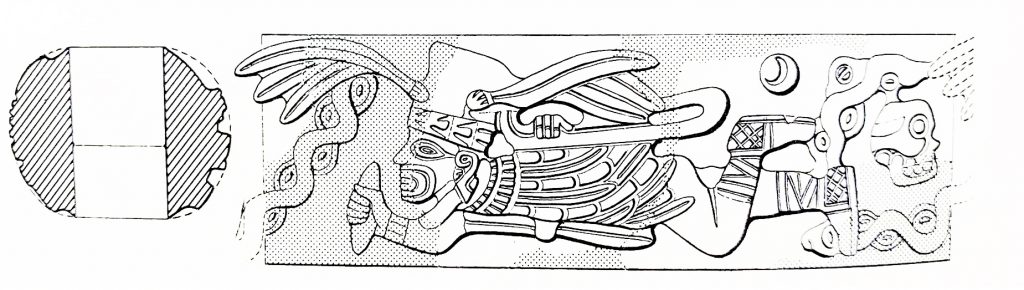

In the northern Maya area during the Terminal Classic period, there is increased emphasis on skull and bone imagery, often on a monumental scale. This trend is illustrated most vividly by the carved stone skull rack at Chichén Itzá, which I have discussed extensively elsewhere (Figure 8.1) (Miller 1999, 2017). In addition to impaled heads in various states of decomposition, the reliefs illustrate warriors with defleshed limbs carrying weapons and human heads. Like skeletal imagery, disembodied eyeballs are also featured in this region at this time. One example is the well-known motif from the Great Ballcourt, of a ball encasing a profile skull with a sort of Mohawk hairstyle ornamented with detached eyeballs (Figure 8.24: Upper).11 The same hairstyle is worn by death deities in the Postclassic screenfolds, including the Dresden and the Madrid codices (Figure 8.7: Lower, Figure 8.19, Figure 8.24: Lower).

Upper: Detail of central relief panel from the Great Ballcourt at Chichén Itzá showing a ball encasing a skull with Mohawk hairstyle and eyeballs in hair. Drawing SD-5058 by Linda Schele@David Schele, courtesy Ancient Americas at LACMA (ancientamericas.org).

Lower: Madrid Codex, page 99c. Detail of death deity with similar hairstyle, also wearing death-eye collar (Vail and Hernández 2018).

Drawing courtesy of Gabrielle Vail.

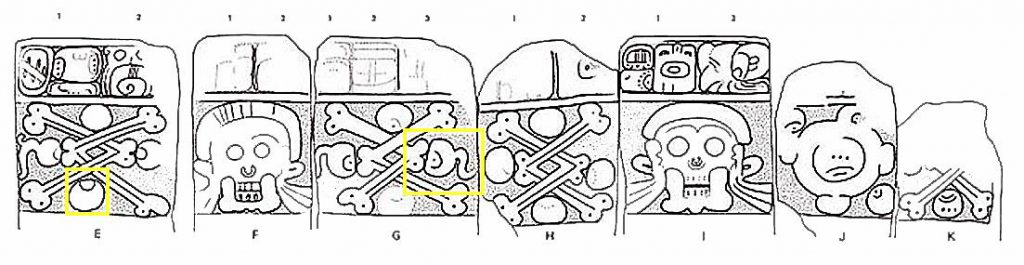

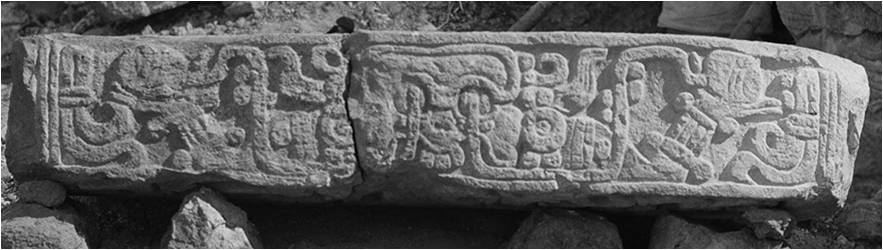

Crossed bones are paired with eyeballs on the reliefs of the low platforms of the so-called Cemetery Group at Uxmal, the largest city in the hilly Puuc area of Yucatán (Figure 8.25). These structures may have served as tzompantlis, but without excavation, this is merely conjecture. Here, eyeballs with optic nerves are represented, as in panels E and G, as well as circles with infixed elements that may represent corneas, most clearly seen at the bottom of panel E (Figure 8.26).12 A similar design, although much simpler, appears on a stone forming part of the wall of a structure on the top of the Nunnery at Chichén Itzá; this stone has been reset from a different structure, but its original context is not known (Figure 8.27). At Nohpat, not far from Uxmal, platforms like those at Uxmal’s Cemetery Group were first reported by John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood (Mayer 2010, 2019). The panels have been looted and are poorly documented, but in a recent drawing of one relief, the detached eyeballs are quite prominent next to crossed femurs (Figure 8.28).

Photo by Virginia E. Miller.

Drawing by Ian Graham (1992: 4:122). © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.9.22.

Photo by Virginia E. Miller.

Drawing by Daniel Graña-Behrens, from Mayer 2010: fig. 23. Used with permission of the artist.

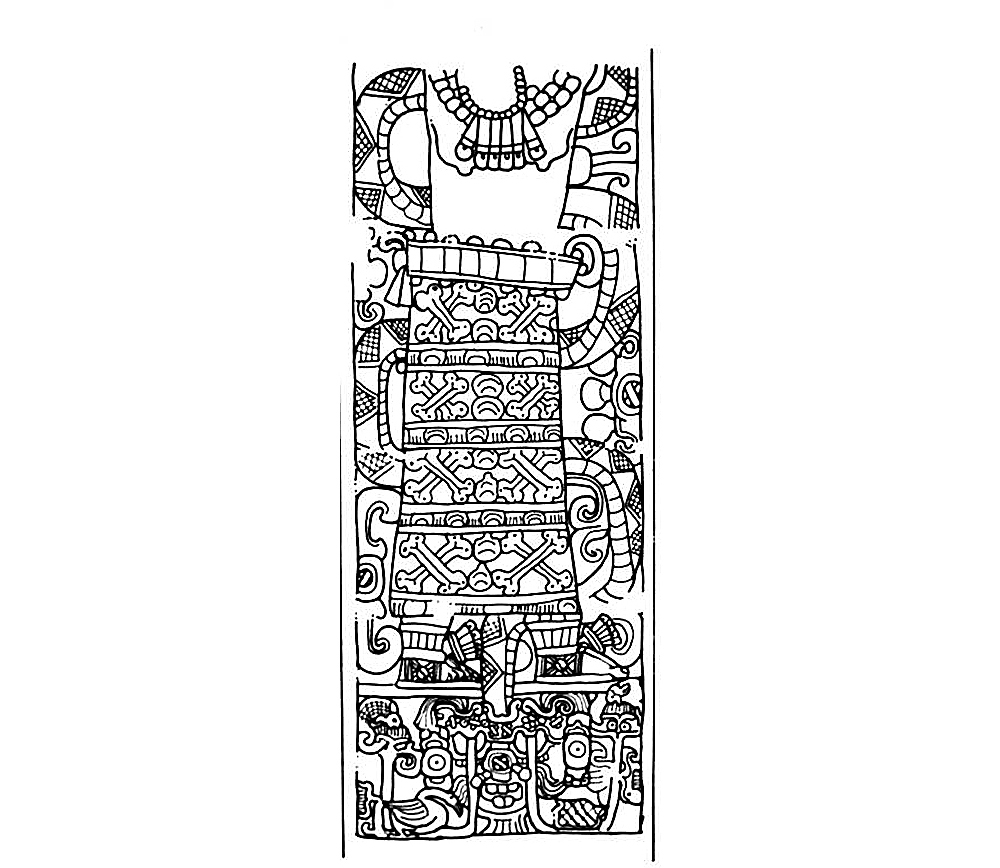

Like Nohpat, Kabah is connected to Uxmal by a sacbe. While no tzompantli has been documented for Kabah, the discovery of a relief during the Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Historia (INAH) excavations there in 2006 demonstrates that the three sites share similar macabre imagery. The basal molding on the exterior of Room 14, at the southern end of the Codz Pop, consists of three rows of carved stones, the upper representing frontal skulls like those at Nohpat and Uxmal. The middle row depicts squat skeletal figures in a squatting, hocker posture with extruded eyeballs that are grasped in each figure’s outstretched hands. Barely visible below are reliefs of crossed bones (Figure 8.29). The chamber in question is not very accessible, being located on the least public façade of the building and contained within another room, suggesting it had a specialized function (Rubenstein 2015: 172). Is it conceivable that this modest, hidden chamber was reserved for body processing? Door jambs from both the Codz Pop and Manos Rojas building feature lively scenes of captive-taking, with captors grasping their victims by the hair (Rubenstein 2015: Figure 79-82, Figure 137-138). Newer reliefs from Kabah include the display of prisoners, participants holding femurs, and a scaffold sacrifice (Rubenstein 2015: 176-185, Figures 152-155, 161-163, 165). A variation on this theme occurs on a carved lintel at Sayil, where a deity holds his own eyeballs in his hands (Figure 8.30) (Houston et al. 2006: 166). Even death gods seem to sport “active” death eyes: the eyeballs perched on the heads of supernatural figures have lines emanating from them almost like speech or breath, suggesting active seeing (Figure 8.19: Right) (Houston et al. 2006: 170).

Photo by Meghan Rubenstein, used with the permission of Lourdes Toscano Hernández.

Gift of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1958. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 58-34-20/28106.

During the Terminal and Postclassic periods the crossed bone, skull, and eyeball designs on clothing became more prominent in monumental art, as well as in the codices. The long skirt of one of four goddesses carved on a pier at the Lower Temple of the Jaguar at Chichén Itzá, for example, bears these motifs (Figure 8.31). Deities of both genders represented in the Dresden Codex also wear items of clothing adorned with the eyeball and crossed bone pattern (Figures 8.19: Right, 8.32). Note that the femurs seem to terminate in eyeballs, as if the artist wished to conflate the two body parts.

Drawing SD-5044 by Linda Schele@David Schele, courtesy Ancient Americas at LACMA (ancientamericas.org).

Upper: Page 28a, Death deity (God A’?) (from Vail and Hernández 2018).

Lower: Page 74, Creation deity Chak Chel.

As noted, heart extraction and decapitation are amply documented in Mesoamerican art and writing. With the aid of the systematic scrutiny of skeletal remains, the varied perimortem treatments of flesh and bone are now more clearly understood (cf. Tiesler 2020). But is there evidence of the deliberate removal of eyeballs, or are the many representations of eyes merely symbolic? In a study of about 200 crania from the Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá, Vera Tiesler (2017: 48; Tiesler and Miller in press) documented signs of eyeball extraction by way of levering in six skulls, all of which displayed marks of soft-tissue detachment (Figure 8.33). While there is no way to ascertain if these particular crania belonged to victims of sacrifice, the evidence of flaying, defleshing, disarticulation, and impalement in so many skulls recovered from the depths of the Cenote makes this the most straightforward explanation.13

Photo by Vera Tiesler, image © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 07-7-20/58224.0.

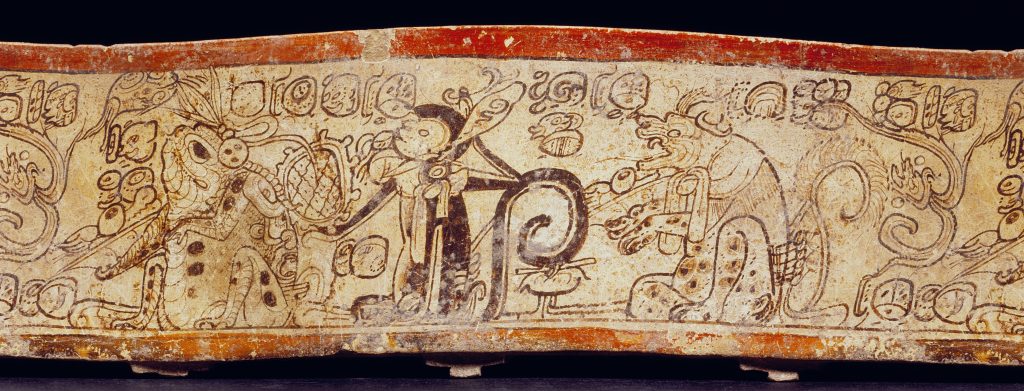

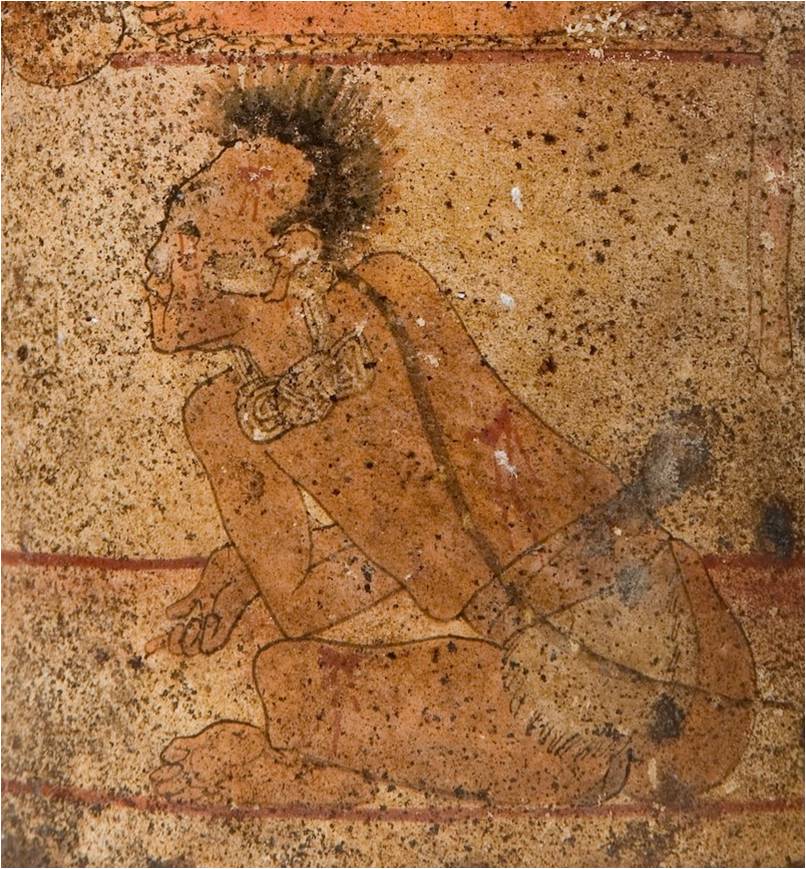

At least one Classic Maya vessel, from the Ik’ corpus, appears to depict a victim of eye removal (Figure 8.34) (Houston 2008; Just 2012: 207).14 A wretched captive, naked, bound, and with chopped off and disheveled hair, sits on the floor below an enthroned lord. He has empty eye sockets and blood streams down his face. Even more ominously, what looks like a heap of flayed human skin lies on the dais before the seated ruler (not shown here) (Beliaev and Houston 2020). The so-called “Wound-by-Obsidian” sign includes a face with unlidded eyes, suggesting that it may represent a flayed human face (Beliaev and Houston 2020). Were sacrificial victims subjected to both eye removal and flaying? One of the Maya hieroglyphs for the verb “to die,” kim or cham, depicts a skull in profile with the eye closed, or perhaps even ripped out (Calvin 2012: 24; Graña-Behrens 2014: 13).

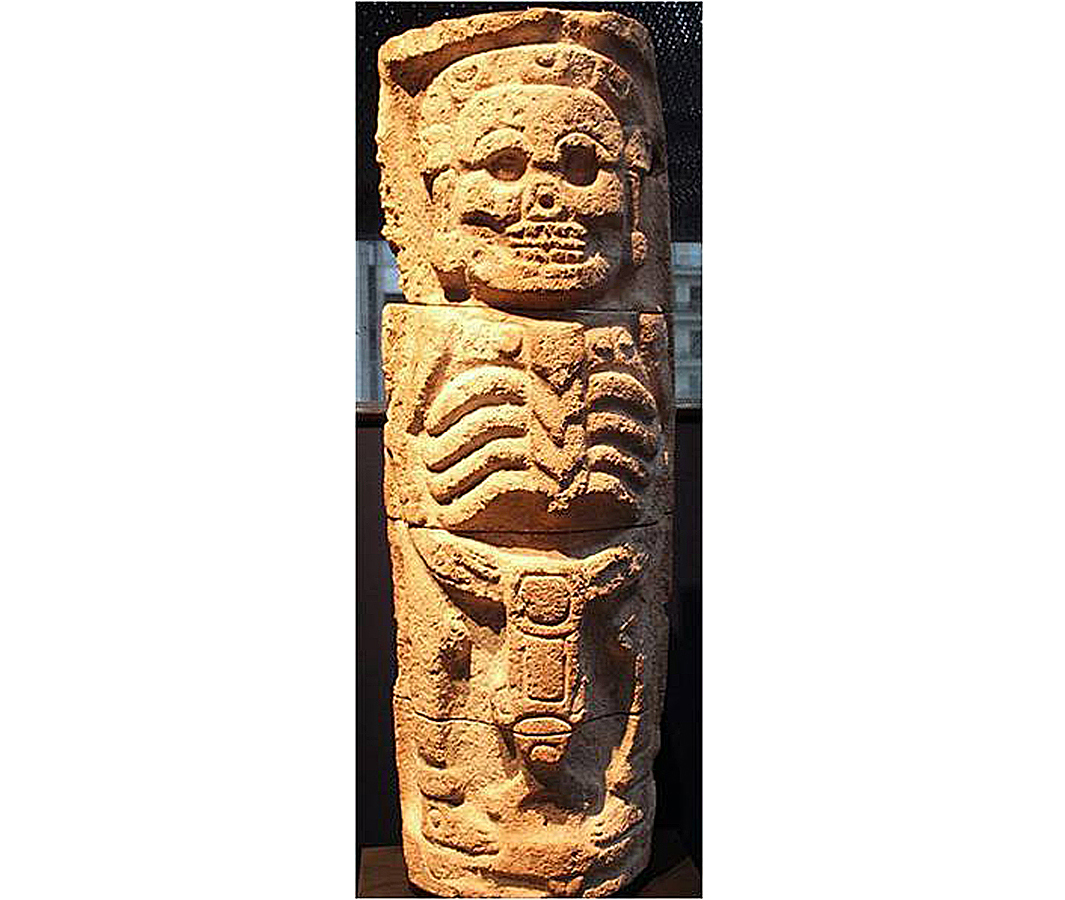

Fleshed human beings whose eyes have been extracted are difficult to locate in the Maya sculptural corpus, but there is one possible example, a carved column now in the Quai Branly Museum in Paris (Figure 8.35). It represents a partially skeletal, ithyphallic figure with deep cavities for the eyes and what looks like a hole for a removable nose (Patrois 2008: 201). He also appears to have eyeballs in his hair or headdress. There are several of these skeletal columns, apparently all from northern Yucatan, but in poor condition, so it is difficult to verify if other examples share these elements (Mayer 1984: 63-64).

Photo courtesy of Guido Krempel.

Of course, it is impossible to know what the Maya actually did with the extracted eyeballs. Were they really worn as ornaments? Could they have been ingested? Were eyeballs gathered and exhibited with other body parts as battle trophies? Or could they have been displayed in processions or performances? There is, for example, an intriguing carved jade bead from Chichén Itza’s Cenote of Sacrifice around which an armed figure appears to float, trailing a skull and a string of what may be eyeballs, although not represented in the usual way (Figure 8.36).

While many still suffer nightmares from having watched Alfred Hitchcock’s movie The Birds (1963), attacks by birds on human eyes are relatively rare (Abdulla and Alkhalifa 2016; The Guardian 2017). Nevertheless, certain birds, such as vultures, will pluck out the eyes of weak or immobile prey, including humans. This act is occasionally represented in Maya art, notably in the Dresden codex where a vulture pulls out the eye of a sacrificial victim (Figure 8.37: Right). Gabrielle Vail (2015: 179: 2021) presents epigraphical and iconographical evidence that this enigmatic scene signifies an eclipse. Her hypothesis finds support among the contemporary Tzotzil Maya who fear eclipses, believing that at that time malignant birds of prey come down and rip out humans’ eyes (Nájera Coronado 1995:322-323).

Left: Madrid Codex 87a (Vail and Hernández 2018).

Drawing courtesy of Gabrielle Vail.

Right: Dresden Codex 3a (Vail and Hernández 2018).

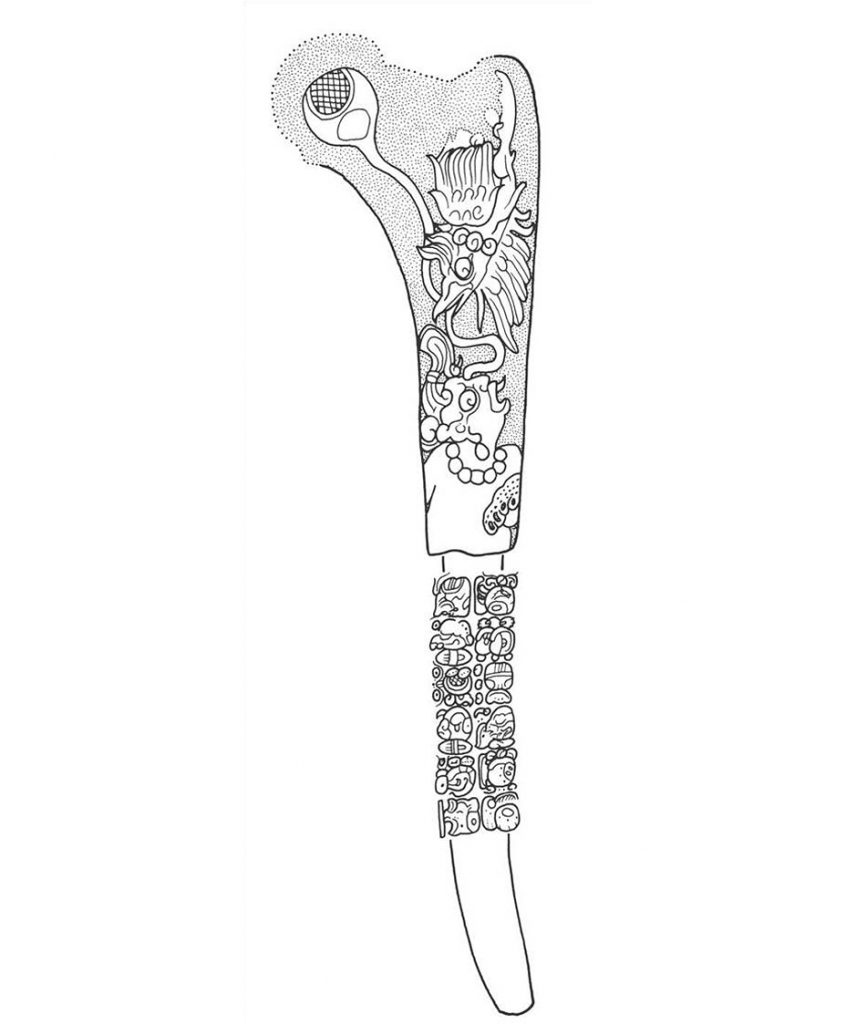

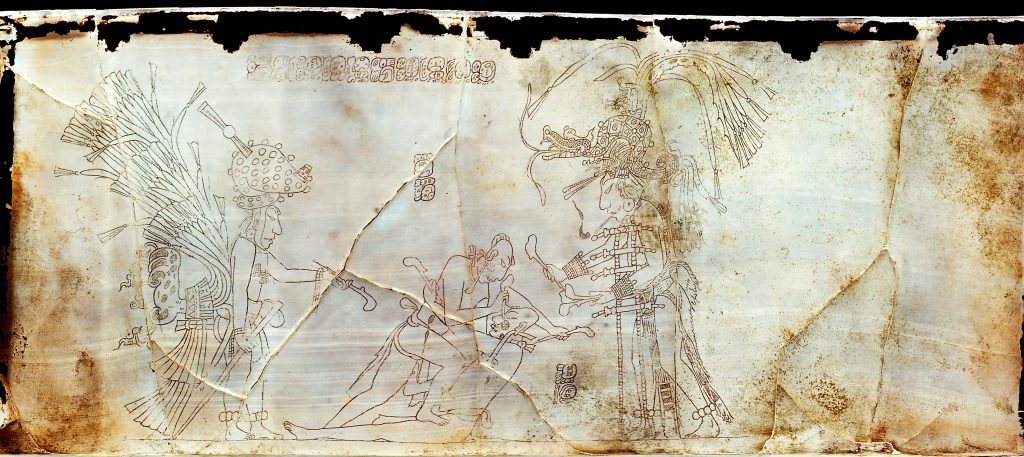

A cremation burial uncovered at Dzibilchaltún in the 1990s contained an exquisitely carved deer bone, apparently belonging to an early 9th century local ruler (Figure 8.38) (Maldonado et al. 2002). According to the object’s excavators, the Jaguar God of the Underworld is losing his eye to a large bird that plunges down from the sky to grasp and pull the optical nerve. The inscription unfortunately does not describe the scene presented, although Gabrielle Vail (personal communication May 2021) suggests that like similar images in the later codices, it may refer to an eclipse.15 While there is no way of knowing whether this sharpened bone was intended for eye removal, it can be compared to a similar object pulled from the Cenote at Chichén Itzá during the explorations of the 1960s (Schmidt 1990:205-206). Probably carved from a human long bone, its handle is shaped to represent a bird not unlike the one depicted on the Dzibilchaltún example. Sharp bone weapons are employed by two fighters on a Late Classic marble vase (Figure 8.39). They are probably captives, accompanied by attendants–possibly their owners or sponsors of the fight–who are at the ready with more daggers (Taube and Zender 2009: 175-176). While the combatants do not appear to be aiming for each other’s eyes, the scene does demonstrate that pointed bones were used as weapons.

Drawing courtesy of Alexander Voss. From Maldonado et al. 2002: fig. 6.

Photo by Justin Kerr, [K7749], Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

Vision was considered a source of power throughout Mesoamerica. In the Mixtec screenfolds, for example, elite figures are often depicted with feathers, smoke, serpents, and other elements emanating from the eyes. These elaborate vision scrolls surely had metaphorical meanings alluding to special powers or authority (Hamann 2004: 84-89). Indeed, for the Maya, losing one’s eyesight signified defeat. The Chilam Balam of Chumayel, a colonial Maya manuscript from Yucatan, describes a series of riddles that would have been used in the past to interrogate and authenticate rulers. Those who failed to answer the questions correctly would be bound, hung by the neck and have the tips of their tongues clipped and their eyes gouged out (Roys 1967:91-92).

According to the mid-sixteenth century Ki’che’ Maya manuscript of the Popol Vuh, the all-seeing creator gods dimmed the eyes of the first humans in order to maintain their potency at a lower level (Christenson 2007:16,197, 200-201). At another point in the creation story, the arrogant Seven Macaw declared himself to be the sun and the moon. Brought down by the actions of the Hero Twins, Seven Macaw’s eyes—glittering blue-green jewels–were plucked out (Christenson 2007: 92,93,100; Vail 2015: 167-168; Hamann 2018: 636). In battles between sky and underworld deities recounted in the Chilam Balam de Chumayel, the sun god’s eyes are put out, once more a probable reference to solar eclipses (Vail 2015:172-173, 175). Postclassic Maya iconography and texts appear to the support the idea that blinding or covering the face of the sun relates not only to eclipses, but also to the end of a previous world age (Vail 2015: 164, 2021).

The act of seeing was understood to be active as well as receptive, having an effect on the viewed as well as the viewer (Houston et al. 2006: 167). In most Mayan languages, “seeing” carries the additional meaning of discerning, understanding, or witnessing while in hieroglyphic texts, those who “see” are always high-status individuals (Houston et al. 2006: 173; Calvin 2012: 29; Brittenham 2019:10-12). The hieroglyphic book on which the Popol Vuh is based was called by its authors an ilb’al, which translates as “instrument of sight or vision”, the same term used today by the Ki’che’ for quartz crystals used in divination, as well as for eyeglasses (Christenson 2007: 34).

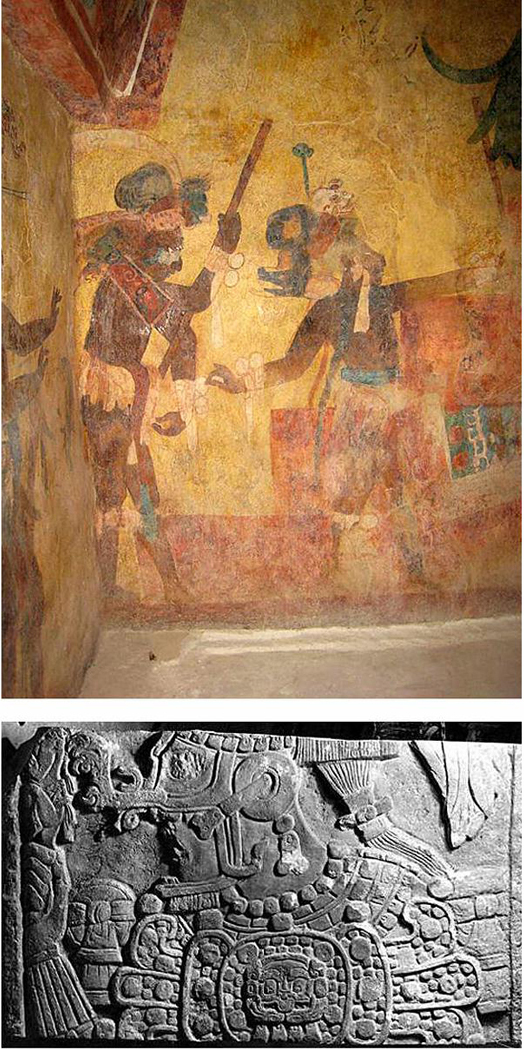

Upper: Bonampak Room 3, detail east wall.

Photo by Virginia E. Miller

Lower: Detail of face on Dos Pilas Stela 11.

Photo courtesy of David Stuart

As several scholars have noted, the active power of the visage is demonstrated in the Classic-era custom of mutilating faces and eyes on sculptures and paintings (Figure 8.40) (Jackson 2019: 33; Houston et al. 2006: 170). Given that the Maya word for both “face” and “eye” is the same (ich), it may not have made a great difference which was obliterated, although in some cases the eyes are specifically targeted. While it has been argued that the defacement of a ruler portrait was a reverential act (O’Neil 2013), it is also likely that such destruction was at times intended as an act of defiance, disrespect, erasure, or even simple post-occupational vandalism. Whatever the intent, the portrait is deactivated, its life–however it was understood by the ancient Maya–taken away (Houston 2014:99-100). In the supernatural realm, on the other hand, eyes continued to have a life of their own.

Notes

1. The deer shown here is a wahyis, named by a double eyeball glyph before his snout (Houston et al., 2006: fig. 4.26b).

2. Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos (personal communication February 2021) reports that there are numerous figures with extruded eyes in the Cotzumalguapa region, e.g. a monumental feline head from the site of Palo Verde (Chinchilla Mazariegos et al. 2001: fig. 8).

3. The ruler represented on newly discovered Stela 47 wears a similar neckpiece, while eyeballs also adorn the figure’s belt and possibly his wrists (Martin 2020: fig. 58).

4. The 4th century ball-player mural from Tikal’s Group 6C-XVI, Structure Sub 39-7 includes a figure who may be wearing eyeballs around his neck (Hurst 2020: fig. 31.5, central figure). I thank Nelda Marengo Camacho (personal communication May 2021) for spotting this detail.

5. Mary E. Miller (personal communication February 2021) suggests that they are maracas, literally “death rattles”.

6. Mary E. Miller (2005) provides a brief discussion of the clothing associated with the aged Maya goddess Chak Chel and later Aztec deities. Jeremy D. Coltman (2018) expands on the theme, with useful illustrations.

7. While most skeletal figures are anthropomorphic, fireflies and mosquitoes are sometimes represented on Classic Maya pottery with skull heads and eyeballs attached to their crania (cf. Chinchilla Mazariegos 2017:fig. 35; www.mayavase.com: K8608). Andrea Stone and Marc Zender (2011: 188-189) suggest that the Maya may have seen a relationship between hard insect carapaces and bones.

8. For a thorough and wide-ranging investigation of the significance of deer for the Maya, see Matthew Looper (2019). This book includes several illustrations of deer wearing the blanket with bones and eyes, including one from a mural at Ek’ Balam (Looper 2019: figs. 7.2, 7.15).

9. A stucco frieze from the Palace of the Fireflies at Toniná, Mexico displays a pair of vividly painted stucco skeletal busts wearing eyeball collars. Large eyeballs on lengthy optic nerves sprout upward from their eye sockets (Yadeun Angulo 2011: 56).

10. Gabrielle Vail (personal communication January 2021), however, suggests that what is represented here is a bone awl inserted in the eye of a blue-painted sacrificial victim.

11. Oddly, dwarfs represented on Classic Maya pottery, especially in the Holmul dancer style, sometimes wear this haircut, albeit without attached eyeballs (cf. www.mayavase.com: K633, K4619).

12. Rivard (1965: 82) recognized these motifs at Uxmal as eyeballs.

13. In the Andean region, the removal of eyes, or of the flesh around the eyes, has been documented in the skeletal record of the Moche, Tiwanaku, and Wari, as well as an Inka period punishment (Becker and Alconini 2018: 245).

14. The Ik’ corpus refers to a large group of Late Classic polychrome ceramics, mostly without provenience, with shared stylistic and epigraphic features. The sign Ik’ (wind, breath or soul) is the main sign of the Emblem Glyph of Motul de San José, near Lake Petén in Guatemala. It is believed to be the center of a kingdom where these vessels were produced (Just 2012).

15. An incised bone, supposedly from Campeche, represents a seated sun deity pulling out the eye of a partially skeletal serpent. Below him, the serpent is held aloft by a supernatural figure with akbal markings and a skeletal mandible, who ascends a ladder or scaffold (Franco 1968: lámina IV). I thank Stephen Houston for directing me to this unique object, the only one of which I am aware where an animal’s eye is pulled by a human.

Acknowledgements

First of all, I thank Vera Tiesler for inviting me to read the first version of this paper in the session Nuevas perspectivas sobre el sacrificio humano, for the XI Congreso Internacional de Mayistas in Chetumal, Mexico, in June 2019. I am grateful for the comments of the session participants and audience in that meeting. A revised version of the paper was presented (virtually) at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in April 2021, once more in a session organized by Tiesler, New Perspectives on Ritual Violence and Related Human Body Treatments in Ancient Mesoamerica. Other colleagues who have provided encouragement and useful information during the preparation of this essay include Claudia Brittenham, Guido Krempel, Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, Stephen Houston, Cecelia Klein, Susan Milbrath, Mary Miller, John Pohl, David Stuart, and especially Gabrielle Vail.

Works Cited

Abdulla, Haitham A. and Saad K. Alkhalifa

2016 “Ruptured Globe Due to a Bird Attack”, Case Reports in Ophthalmology 7(1): 112-114.

Becker, Sara K. and Sonia Alconini

2018 “Violence, Power, and Head Extraction in the Kallawaya Region, Bolivia”. In Social Skins of the Head: Body Beliefs and Ritual in Ancient Mesoamerica and the Andes, Vera Tiesler and María Cecilia Lozada, eds., pp. 235-252. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Beliaev, Dmitri and Stephen Houston

2020 “A Sacrificial Sign in Maya Writing”. In Maya Decipherment. https://mayadecipherment.com/

Boone, Elizabeth Hill and Rochelle Collins

2013 “The Petroglyphic Prayers on the Sun Stone of Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina”, Ancient Mesoamerica 24: 225-241.

Brady, James E. and Jeremy D. Coltman

2016 “Bats and the Camazotz: Correcting a Century of Mistaken Identity”, Latin American Antiquity 27(2): 227-237.

Brittenham, Claudia

2019 “Architecture, Vision, and Ritual: Seeing Maya Lintels at Yaxchilan Structure 23”, Art Bulletin 101(3) September: 8-36.

Calvin, Inga

2012 Maya Hieroglyphics Study Guide. http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/calvin/index.html

n.d. (2021) Mesoamerican Pottery Database. http://research.famsi.org/rollouts/index.html

Carter, Nicholas, et al.

2020 “The Clothed Body”. In The Adorned Body: Mapping Ancient Maya Dress, Nicholas Carter, Stephen D. Houston, and Franco D. Rossi, eds., pp. 9-31. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Chacon, Richard and Richard Dye, eds.

2007 The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts as Trophies by Amerindians. New York: Springer.

Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo

2014 “Flaying, Dismemberment, and Ritual Human Sacrifice on the Pacific Coast of Guatemala”, The PARI Journal 14(3): 1-12.

2017 Art and Myth of the Ancient Maya. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo, et al.

2001 “Palo Verde. Un centro secundario en la zona de Cotzumalguapa”, Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Vol. 87, pp. 303-324.

Christenson, Allen J.

2007 Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Coltman, Jeremy D.

2018 “Where Night Reigns Eternal: Darkness and Deep Time Among the Ancient Maya”. In Archaeology of the Night: Life After Dark in the Ancient World, Nancy Gonlin and April Nowell, eds., pp. 201-222. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

2021 “The Cave and the Skirt: A Consideration of Classic Maya Ch’een Symbolism”, in Night and Darkness in Ancient Mesoamerica, Nancy Gonlin and David M. Reed, eds., pp. 201-224. Louisville: University Press of Colorado.

Franco C, José Luis

1968 Objetos de hueso de la época precolombina. Mexico City: Museo Nacional de Antropología.

Garton, John, and Karl Taube

2017 “An Olmec Style Statuette in the Worcester Art Museum”, Mexicon 39: 2 29, 35-40.

Graham, Ian

1978 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Vol. 2, Part 2 (Naranjo, Chunhuitz, Xunatunich). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

1992 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Vol. 4 Part 2 (Uxmal). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Graña-Behrens, Daniel

2014 “Death and Deer Riding Among the Ancient Maya of Northwest Yucatan, Mexico”. In The Archaeology of Yucatan: New Directions and Data, Travis W. Stanton, ed., pp. 3-20. Oxford: Archaeopress.

The Guardian

2017 “Surge in Eye Injuries as Melbourne Magpies Go On Attack Spree”.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/oct/19/surge-in-eye-injuries-as-melbourne-magpies-go-on-attack-spree

Hamann, Byron Ellsworth

2004 “In the Eyes of the Mixtecs/To View Several Pages Simultaneously’: Seeing and the Mixtec Screenfolds”, Visible Language 38(1):68-123.

2018 “The Higa and the Tlachialoni: Material Cultures of Seeing in the Mediterratlantic”, Art History 41(4): 624- 649.

Helmke, Christophe

2020 “Tactics, Trophies and Titles: A Comparative Perspective on Ancient Maya Raiding”, Ancient Mesoamerica 31: 29-46.

Houston, Stephen

2008 “A Classic Maya Bailiff?”, Maya Decipherment, https://mayadecipherment.com/

2014 The Life Within: Classic Maya and the Matter of Permanence. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Houston, Stephen, et al.

2006 The Memory of Bones: Body, Being and Experience Among the Classic Maya. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Hurst, Heather

2020 “Maya Mural Painting”. In The Maya World, Scott R. Hutson and Traci Ardren, eds., pp. 578-598. London and New York: Routledge.

Jackson, Sara E.

2019 “Facing Objects: an Investigation of Non-human Personhood in Classic Maya Contexts”, Ancient Mesoamerica 30: 31-44.

Just, Bryan

2012 Dancing into Dreams. Maya Vase Painting of the Ik’ Kingdom. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kerr, Justin

n.d. (2021) Maya Vase Database: An Archive of Rollout Photographs. www.mayavase.com

Krempel, Guido

2015 “Capítulo XXIX, Análisis iconográfico y epigráfico de vasijas polícromas con inscripciones: Temporada 2014”. In Proyecto Arqueológico Regional SAHI-Uaxactun, Informe no. 6, Temporada de Campo 2014, Milan Kováč and Silvia Alvarado Najarro, eds., pp. 563-580. Bratislava: Instituto Eslovaco de Arqueología e Historia. Report submitted to the Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala.

Looper, Matthew

2019 The Beast Between: Deer in Maya Art and Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Maldonado, Rubén, et al.

2002 “Kalom Uk’uw, señor de Dzibilchaltun”. In La Organización Social Entre Los Mayas. Memoria de la Tercera Mesa Redonda de Palenque, Vol. 1, Vera Tiesler et al., eds., pp. 79–100. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán.

Martin, Simon

2020 Ancient Maya Politics: A Political Anthropology of the Classic Period 150-900 CE. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, Karl Herbert

1984 Maya Monuments: Sculptures of Unknown Provenance in Middle America. Berlin: Verlag Karl-Friedrich von Flemming.

2010 “Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions from Nohpat, Yucatan, Mexico”, Mexicon 23 (1-2): 9-13.

2019 “Monument 1 of Nohpat, Yucatan, Mexico”, Mexicon 41(5):121-125.

Merk, Stephan and Guido Krempel

2017 “Two Unprovenanced Maya Sculptures in a Private Collection in Merida”, Mexicon 39(4): 83-85.

Milbrath, Susan

1999 Star Gods of the Maya. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Miller, Mary E.

2005 “Rethinking Jaina: Goddesses, Skirts, and the Jolly Roger”, Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University 64: 63-70.

Miller, Virginia E.

1989 “Star Warriors at Chichen Itza”. In Word and Image in Maya Culture: Explorations in Language, Writing, and Representation, William F. Hanks and Don S. Rice, eds., pp. 287-305. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

1999 “The Skull Rack in Mesoamerica”. In Mesoamerican Architecture as a Cultural Symbol, Jeff K. Kowalski, ed., pp. 340-360. New York: Oxford University Press.

2007 “Skeletons, Skulls, and Bones in the Art of Chichén Itzá”. In New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society, Vera Tiesler and Andrea Cucina, eds., pp. 165-189. New York: Springer.

2017 “Tzompantlis: Un Espejo en el Arte Maya”, Arqueología Mexicana 25(148): 40-45.

Nájera Coronado, Marta Ilía

1995 “El Temor a Los Eclipses Entre Comunidades Mayas Contemporáneas”. In Religión y Sociedad en el Área Maya, Carmen Varela Torrecilla et al., eds., pp. 319-327. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas, Pub. 3.

O’Neil, Megan

2013 “Marked Faces, Displaced Bodies: Monument Breakage and Reuse Among the Classic-Period Maya”. In Striking Images, Iconoclasms Past and Present. Stacy Boldrick et al., eds., pp. 47-64. Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing, Inc.

Patrois, Julie

2008 “Etude Iconographique des Sculptures du Nord de la Péninsule du Yucatán”. In Paris Monographs in American Archaeology, British Archaeological Reports n°20, Oxford, England: International Series, 297.

Proskouriakoff, Tatiana

1974 Jades from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichen Itza, Yucatan: Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 10, No. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Rivard, Jean-Jacques

1965 “Cascabeles y Ojos del Dios Maya de la Muerte, Ah Puch”, Estudios de Cultura Maya 5: 75-91.

Rubenstein, Meghan

2015 Animate Architecture at Kabah: Terminal Classic Art and Politics in the Puuc Region of Yucatán, Mexico. PhD Dissertation, Department of Art History, Austin: The University of Texas at Austin.

Schele, Linda

n.d. (2021) Schele Drawing Collection, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, http://ancientamericas.org/artist/linda-schele

Schmidt, Peter J.

1990 “Chichen Itza and Prosperity in Yucatan”. In Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries, pp. 182-211. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Stone, Andrea and Marc Zender

2011 Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. London: Thames & Hudson.

Taube, Karl

2017 “Los “Andamios de Cráneos” Entre los Antiguos Mayas”, Arqueología Mexicana 25(148): 28-33.

2018 Studies in Ancient American Art and Architecture: Selected Works by Karl Andreas Taube, Volume 1. Precolumbia Mesoweb Press: http://www.mesoweb.com/publications/Works/Taube_Works_v1.s.pdf

Taube, Karl and Marc Zender

2009 “American Gladiators: Ritual Boxing in Ancient Mesoamerica”. In Blood and Beauty: Organized Violence in the Art and Archaeology of Mesoamerica and Central America, Heather Orr and Rex Koontz, eds., pp. 161-220. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California at Los Angeles.

Tiesler, Vera

2017 “Cráneos Perforados y Tzompantlis en Chichén Itzá”, Arqueología Mexicana 25(148): 42-47.

2020 “Feeding the Gods. Sequences and Meanings of Human Sacrifice, Ritual Body Processing, and Exhibition Among the Ancient Maya”. In Rituelle Gewalt, Gewaltrituale. XX Tagung der Landesmuseums für Vorgeschicht, Halle, 2019, Harald Meller et al., eds., pp. 1-18. Halle, Germany.

Tiesler, Vera and Virginia E. Miller

2021 “Heads, Skulls, and Sacred Scaffolds: New Studies on Tzompantlis in Mesoamerica”. For special issue of Ancient Mesoamerica on Chichén Itzá, Rafael Cobos, ed. In press.

Vail, Gabrielle

2015 “Iconography and Metaphorical Expressions Pertaining to Eclipses: A Perspective from Postclassic and Colonial Manuscripts”. In Cosmology, Calendars, and Horizon-Based Astronomy in Ancient Mesoamerica, Anne S. Dowd and Susan Milbrath, eds., pp. 163-196. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

2021 “Celestial and Underworld Deities in Postclassic and Colonial Maya Narratives”. In Indigenous Conceptions of the Sky in Mesoamerica and the Andes, Gabrielle Vail, ed. Peter Lang, New York. Under review.

Vail, Gabrielle, and Christine Hernández

2018 The Maya Codices Database, Version, 5.0. http://www.mayacodices.org/.

Velásquez García, Erik

2015 “Spirit Entities and Forces in Classic Maya Cosmovision”. In The Maya: Voices in Stone, Alejandra Martínez de Velasco Cortina and María Elena Vega Villalobos, eds., pp. 177-195. Mexico: Turner/Ambar Diseño/UNAM.

Yadeun Angulo, Juan

2011 “K’inich Baak Nal Chaak (Resplandeciente Señor de la Lluvia y el Inframundo) (652-707 d.C.) Toniná (Popo), Chiapas”, Arqueología Mexicana 19 (110): 52-57.