|

Buy this book at Amazon.com

Chapter 10 Lists

This chapter presents one of Python’s most useful built-in types, lists.

You will also learn more about objects and what can happen when you have

more than one name for the same object.

10.1 A list is a sequence

Like a string, a list is a sequence of values. In a string, the

values are characters; in a list, they can be any type. The values in

a list are called elements or sometimes items.

There are several ways to create a new list; the simplest is to

enclose the elements in square brackets ([ and ]):

[10, 20, 30, 40]

['crunchy frog', 'ram bladder', 'lark vomit']

The first example is a list of four integers. The second is a list of

three strings. The elements of a list don’t have to be the same type.

The following list contains a string, a float, an integer, and

(lo!) another list:

['spam', 2.0, 5, [10, 20]]

A list within another list is nested.

A list that contains no elements is

called an empty list; you can create one with empty

brackets, [].

As you might expect, you can assign list values to variables:

>>> cheeses = ['Cheddar', 'Edam', 'Gouda']

>>> numbers = [42, 123]

>>> empty = []

>>> print(cheeses, numbers, empty)

['Cheddar', 'Edam', 'Gouda'] [42, 123] []

10.2 Lists are mutable

The syntax for accessing the elements of a list is the same as for

accessing the characters of a string—the bracket operator. The

expression inside the brackets specifies the index. Remember that the

indices start at 0:

>>> cheeses[0]

'Cheddar'

Unlike strings, lists are mutable. When the bracket operator appears

on the left side of an assignment, it identifies the element of the

list that will be assigned.

>>> numbers = [42, 123]

>>> numbers[1] = 5

>>> numbers

[42, 5]

The one-eth element of numbers, which

used to be 123, is now 5.

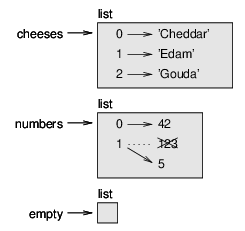

Figure 10.1 shows

the state diagram for cheeses, numbers and empty:

| Figure 10.1: State diagram. |

Lists are represented by boxes with the word “list” outside

and the elements of the list inside. cheeses refers to

a list with three elements indexed 0, 1 and 2.

numbers contains two elements; the diagram shows that the

value of the second element has been reassigned from 123 to 5.

empty refers to a list with no elements.

List indices work the same way as string indices:

- Any integer expression can be used as an index.

- If you try to read or write an element that does not exist, you

get an IndexError.

- If an index has a negative value, it counts backward from the

end of the list.

The in operator also works on lists.

>>> cheeses = ['Cheddar', 'Edam', 'Gouda']

>>> 'Edam' in cheeses

True

>>> 'Brie' in cheeses

False

10.3 Traversing a list

The most common way to traverse the elements of a list is

with a for loop. The syntax is the same as for strings:

for cheese in cheeses:

print(cheese)

This works well if you only need to read the elements of the

list. But if you want to write or update the elements, you

need the indices. A common way to do that is to combine

the built-in functions range and len:

for i in range(len(numbers)):

numbers[i] = numbers[i] * 2

This loop traverses the list and updates each element. len

returns the number of elements in the list. range returns

a list of indices from 0 to n−1, where n is the length of

the list. Each time through the loop i gets the index

of the next element. The assignment statement in the body uses

i to read the old value of the element and to assign the

new value.

A for loop over an empty list never runs the body:

for x in []:

print('This never happens.')

Although a list can contain another list, the nested

list still counts as a single element. The length of this list is

four:

['spam', 1, ['Brie', 'Roquefort', 'Pol le Veq'], [1, 2, 3]]

10.4 List operations

The + operator concatenates lists:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [4, 5, 6]

>>> c = a + b

>>> c

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

The * operator repeats a list a given number of times:

>>> [0] * 4

[0, 0, 0, 0]

>>> [1, 2, 3] * 3

[1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3]

The first example repeats [0] four times. The second example

repeats the list [1, 2, 3] three times.

10.5 List slices

The slice operator also works on lists:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> t[1:3]

['b', 'c']

>>> t[:4]

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> t[3:]

['d', 'e', 'f']

If you omit the first index, the slice starts at the beginning.

If you omit the second, the slice goes to the end. So if you

omit both, the slice is a copy of the whole list.

>>> t[:]

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

Since lists are mutable, it is often useful to make a copy

before performing operations that modify lists.

A slice operator on the left side of an assignment

can update multiple elements:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> t[1:3] = ['x', 'y']

>>> t

['a', 'x', 'y', 'd', 'e', 'f']

10.6 List methods

Python provides methods that operate on lists. For example,

append adds a new element to the end of a list:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> t.append('d')

>>> t

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

extend takes a list as an argument and appends all of

the elements:

>>> t1 = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> t2 = ['d', 'e']

>>> t1.extend(t2)

>>> t1

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

This example leaves t2 unmodified.

sort arranges the elements of the list from low to high:

>>> t = ['d', 'c', 'e', 'b', 'a']

>>> t.sort()

>>> t

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

Most list methods are void; they modify the list and return None.

If you accidentally write t = t.sort(), you will be disappointed

with the result.

10.7 Map, filter and reduce

To add up all the numbers in a list, you can use a loop like this:

def add_all(t):

total = 0

for x in t:

total += x

return total

total is initialized to 0. Each time through the loop,

x gets one element from the list. The += operator

provides a short way to update a variable. This

augmented assignment statement,

total += x

is equivalent to

total = total + x

As the loop runs, total accumulates the sum of the

elements; a variable used this way is sometimes called an

accumulator.

Adding up the elements of a list is such a common operation

that Python provides it as a built-in function, sum:

>>> t = [1, 2, 3]

>>> sum(t)

6

An operation like this that combines a sequence of elements into

a single value is sometimes called reduce.

Sometimes you want to traverse one list while building

another. For example, the following function takes a list of strings

and returns a new list that contains capitalized strings:

def capitalize_all(t):

res = []

for s in t:

res.append(s.capitalize())

return res

res is initialized with an empty list; each time through

the loop, we append the next element. So res is another

kind of accumulator.

An operation like capitalize_all is sometimes called a map because it “maps” a function (in this case the method capitalize) onto each of the elements in a sequence.

Another common operation is to select some of the elements from

a list and return a sublist. For example, the following

function takes a list of strings and returns a list that contains

only the uppercase strings:

def only_upper(t):

res = []

for s in t:

if s.isupper():

res.append(s)

return res

isupper is a string method that returns True if

the string contains only upper case letters.

An operation like only_upper is called a filter because

it selects some of the elements and filters out the others.

Most common list operations can be expressed as a combination

of map, filter and reduce.

10.8 Deleting elements

There are several ways to delete elements from a list. If you

know the index of the element you want, you can use

pop:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> x = t.pop(1)

>>> t

['a', 'c']

>>> x

'b'

pop modifies the list and returns the element that was removed.

If you don’t provide an index, it deletes and returns the

last element.

If you don’t need the removed value, you can use the del

operator:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> del t[1]

>>> t

['a', 'c']

If you know the element you want to remove (but not the index), you

can use remove:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> t.remove('b')

>>> t

['a', 'c']

The return value from remove is None.

To remove more than one element, you can use del with

a slice index:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> del t[1:5]

>>> t

['a', 'f']

As usual, the slice selects all the elements up to but not

including the second index.

10.9 Lists and strings

A string is a sequence of characters and a list is a sequence

of values, but a list of characters is not the same as a

string. To convert from a string to a list of characters,

you can use list:

>>> s = 'spam'

>>> t = list(s)

>>> t

['s', 'p', 'a', 'm']

Because list is the name of a built-in function, you should

avoid using it as a variable name. I also avoid l because

it looks too much like 1. So that’s why I use t.

The list function breaks a string into individual letters. If

you want to break a string into words, you can use the split

method:

>>> s = 'pining for the fjords'

>>> t = s.split()

>>> t

['pining', 'for', 'the', 'fjords']

An optional argument called a delimiter specifies which

characters to use as word boundaries.

The following example

uses a hyphen as a delimiter:

>>> s = 'spam-spam-spam'

>>> delimiter = '-'

>>> t = s.split(delimiter)

>>> t

['spam', 'spam', 'spam']

join is the inverse of split. It

takes a list of strings and

concatenates the elements. join is a string method,

so you have to invoke it on the delimiter and pass the

list as a parameter:

>>> t = ['pining', 'for', 'the', 'fjords']

>>> delimiter = ' '

>>> s = delimiter.join(t)

>>> s

'pining for the fjords'

In this case the delimiter is a space character, so

join puts a space between words. To concatenate

strings without spaces, you can use the empty string,

'', as a delimiter.

10.10 Objects and values

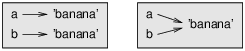

If we run these assignment statements:

a = 'banana'

b = 'banana'

We know that a and b both refer to a

string, but we don’t

know whether they refer to the same string.

There are two possible states, shown in Figure 10.2.

| Figure 10.2: State diagram. |

In one case, a and b refer to two different objects that

have the same value. In the second case, they refer to the same

object.

To check whether two variables refer to the same object, you can

use the is operator.

>>> a = 'banana'

>>> b = 'banana'

>>> a is b

True

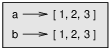

In this example, Python only created one string object, and both a and b refer to it. But when you create two lists, you get

two objects:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [1, 2, 3]

>>> a is b

False

So the state diagram looks like Figure 10.3.

| Figure 10.3: State diagram. |

In this case we would say that the two lists are equivalent,

because they have the same elements, but not identical, because

they are not the same object. If two objects are identical, they are

also equivalent, but if they are equivalent, they are not necessarily

identical.

Until now, we have been using “object” and “value”

interchangeably, but it is more precise to say that an object has a

value. If you evaluate [1, 2, 3], you get a list

object whose value is a sequence of integers. If another

list has the same elements, we say it has the same value, but

it is not the same object.

10.11 Aliasing

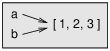

If a refers to an object and you assign b = a,

then both variables refer to the same object:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a

>>> b is a

True

The state diagram looks like Figure 10.4.

| Figure 10.4: State diagram. |

The association of a variable with an object is called a reference. In this example, there are two references to the same

object.

An object with more than one reference has more

than one name, so we say that the object is aliased.

If the aliased object is mutable, changes made with one alias affect

the other:

>>> b[0] = 42

>>> a

[42, 2, 3]

Although this behavior can be useful, it is error-prone. In general,

it is safer to avoid aliasing when you are working with mutable

objects.

For immutable objects like strings, aliasing is not as much of a

problem. In this example:

a = 'banana'

b = 'banana'

It almost never makes a difference whether a and b refer

to the same string or not.

10.12 List arguments

When you pass a list to a function, the function gets a reference to

the list. If the function modifies the list, the caller sees

the change. For example, delete_head removes the first element

from a list:

def delete_head(t):

del t[0]

Here’s how it is used:

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> delete_head(letters)

>>> letters

['b', 'c']

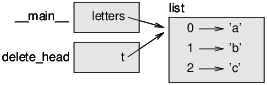

The parameter t and the variable letters are

aliases for the same object. The stack diagram looks like

Figure 10.5.

| Figure 10.5: Stack diagram. |

Since the list is shared by two frames, I drew

it between them.

It is important to distinguish between operations that

modify lists and operations that create new lists. For

example, the append method modifies a list, but the

+ operator creates a new list.

Here’s an example using append:

>>> t1 = [1, 2]

>>> t2 = t1.append(3)

>>> t1

[1, 2, 3]

>>> t2

None

The return value from append is None.

Here’s an example using the + operator:

>>> t3 = t1 + [4]

>>> t1

[1, 2, 3]

>>> t3

[1, 2, 3, 4]

The result of the operator is a new list, and the original list is

unchanged.

This difference is important when you write functions that

are supposed to modify lists. For example, this function

does not delete the head of a list:

def bad_delete_head(t):

t = t[1:] # WRONG!

The slice operator creates a new list and the assignment

makes t refer to it, but that doesn’t affect the caller.

>>> t4 = [1, 2, 3]

>>> bad_delete_head(t4)

>>> t4

[1, 2, 3]

At the beginning of bad_delete_head, t and t4

refer to the same list. At the end, t refers to a new list,

but t4 still refers to the original, unmodified list.

An alternative is to write a function that creates and

returns a new list. For

example, tail returns all but the first

element of a list:

def tail(t):

return t[1:]

This function leaves the original list unmodified.

Here’s how it is used:

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> rest = tail(letters)

>>> rest

['b', 'c']

10.13 Debugging

Careless use of lists (and other mutable objects)

can lead to long hours of debugging. Here are some common

pitfalls and ways to avoid them:

- Most list methods modify the argument and

return None. This is the opposite of the string methods,

which return a new string and leave the original alone.

If you are used to writing string code like this:

word = word.strip()

It is tempting to write list code like this:

t = t.sort() # WRONG!

Because sort returns None, the

next operation you perform with t is likely to fail.

Before using list methods and operators, you should read the

documentation carefully and then test them in interactive mode.

- Pick an idiom and stick with it.

Part of the problem with lists is that there are too many

ways to do things. For example, to remove an element from

a list, you can use pop, remove, del,

or even a slice assignment.

To add an element, you can use the append method or

the + operator. Assuming that t is a list and

x is a list element, these are correct:

t.append(x)

t = t + [x]

t += [x]

And these are wrong:

t.append([x]) # WRONG!

t = t.append(x) # WRONG!

t + [x] # WRONG!

t = t + x # WRONG!

Try out each of these examples in interactive mode to make sure

you understand what they do. Notice that only the last

one causes a runtime error; the other three are legal, but they

do the wrong thing.

- Make copies to avoid aliasing.

If you want to use a method like sort that modifies

the argument, but you need to keep the original list as

well, you can make a copy.

>>> t = [3, 1, 2]

>>> t2 = t[:]

>>> t2.sort()

>>> t

[3, 1, 2]

>>> t2

[1, 2, 3]

In this example you could also use the built-in function sorted,

which returns a new, sorted list and leaves the original alone.

>>> t2 = sorted(t)

>>> t

[3, 1, 2]

>>> t2

[1, 2, 3]

10.14 Glossary

- list:

- A sequence of values.

- element:

- One of the values in a list (or other sequence),

also called items.

- nested list:

- A list that is an element of another list.

- accumulator:

- A variable used in a loop to add up or

accumulate a result.

- augmented assignment:

- A statement that updates the value

of a variable using an operator like +=.

- reduce:

- A processing pattern that traverses a sequence

and accumulates the elements into a single result.

- map:

- A processing pattern that traverses a sequence and

performs an operation on each element.

- filter:

- A processing pattern that traverses a list and

selects the elements that satisfy some criterion.

- object:

- Something a variable can refer to. An object

has a type and a value.

- equivalent:

- Having the same value.

- identical:

- Being the same object (which implies equivalence).

- reference:

- The association between a variable and its value.

- aliasing:

- A circumstance where two or more variables refer to the same

object.

- delimiter:

- A character or string used to indicate where a

string should be split.

10.15 Exercises

You can download solutions to these exercises from

http://thinkpython2.com/code/list_exercises.py.

Exercise 1

Write a function called nested_sum that takes a list of lists

of integers and adds up the elements from all of the nested lists.

For example:

>>> t = [[1, 2], [3], [4, 5, 6]]

>>> nested_sum(t)

21

Exercise 2

Write a function called cumsum that takes a list of numbers and

returns the cumulative sum; that is, a new list where the ith

element is the sum of the first i+1 elements from the original list.

For example:

>>> t = [1, 2, 3]

>>> cumsum(t)

[1, 3, 6]

Exercise 3

Write a function called middle that takes a list and

returns a new list that contains all but the first and last

elements. For example:

>>> t = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> middle(t)

[2, 3]

Exercise 4

Write a function called chop that takes a list, modifies it

by removing the first and last elements, and returns None.

For example:

>>> t = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> chop(t)

>>> t

[2, 3]

Exercise 5

Write a function called is_sorted that takes a list as a

parameter and returns True if the list is sorted in ascending

order and False otherwise. For example:

>>> is_sorted([1, 2, 2])

True

>>> is_sorted(['b', 'a'])

False

Exercise 6

Two words are anagrams if you can rearrange the letters from one

to spell the other. Write a function called is_anagram

that takes two strings and returns True if they are anagrams.

Exercise 7

Write a function called has_duplicates that takes

a list and returns True if there is any element that

appears more than once. It should not modify the original

list.

Exercise 8

This exercise pertains to the so-called Birthday Paradox, which you

can read about at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birthday_paradox.

If there are 23 students in your class, what are the chances

that two of you have the same birthday? You can estimate this

probability by generating random samples of 23 birthdays

and checking for matches. Hint: you can generate random birthdays

with the randint function in the random module.

You can download my

solution from http://thinkpython2.com/code/birthday.py.

Exercise 9

Write a function that reads the file words.txt and builds

a list with one element per word. Write two versions of

this function, one using the append method and the

other using the idiom t = t + [x]. Which one takes

longer to run? Why?

Solution: http://thinkpython2.com/code/wordlist.py.

Exercise 10

To check whether a word is in the word list, you could use

the in operator, but it would be slow because it searches

through the words in order.

Because the words are in alphabetical order, we can speed things up

with a bisection search (also known as binary search), which is

similar to what you do when you look a word up in the dictionary (the book, not the data structure). You

start in the middle and check to see whether the word you are looking

for comes before the word in the middle of the list. If so, you

search the first half of the list the same way. Otherwise you search

the second half.

Either way, you cut the remaining search space in half. If the

word list has 113,809 words, it will take about 17 steps to

find the word or conclude that it’s not there.

Write a function called in_bisect that takes a sorted list

and a target value and returns True if the word is

in the list and False if it’s not.

Or you could read the documentation of the bisect module

and use that! Solution: http://thinkpython2.com/code/inlist.py.

Exercise 12

Two words “interlock” if taking alternating letters from each forms

a new word. For example, “shoe” and “cold”

interlock to form “schooled”.

Solution: http://thinkpython2.com/code/interlock.py.

Credit: This exercise is inspired by an example at http://puzzlers.org.

- Write a program that finds all pairs of words that interlock.

Hint: don’t enumerate all pairs!

- Can you find any words that are three-way interlocked; that is,

every third letter forms a word, starting from the first, second or

third?

Buy this book at Amazon.com

|