3 The Recording Process

Learning Objectives

- Explain what an account is and how it helps in the recording process.

- Define debits and credits and explain how they are used to record business transactions.

- Identify the basic steps in the recording process.

- Explain what a journal is and how it helps in the recording process.

- Explain what a ledger is and how it helps in the recording process.

- Explain what posting is and how it helps in the recording process.

- Prepare a trial balance and explain its purposes.

An Account

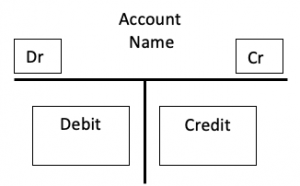

An account in an individual accounting record of increases and decreases in a specific asset, liability or stockholders’ equity item. An account always has two sides – debit and credit. An account can be expressed as a “T-account”. The reason is that the letter T sort of divides any space into the left side and the right side, Therefore, in a T-account, the title or the name of the account is always written on the top of the T with the left side of the T being the debit and the right side of the T being the credit.

Thus,

- Debit – Means “left”, often abbreviated “Dr.”

- Credit – Means “right”, often abbreviated “Cr.”

- In accounting – For every debit, there is credit!

- Debits MUST equal Credits – and this is also known as the double-entry system.

If at the end of any account analysis your debits do not equal to your credits, you know you have made a mistake!

Debits and Credits

Debits and credits of accounts only mean the left sides and the right sides. It is the account itself, its type, that determines and defines how debits and credits will affect the account. You often heard, my credit cards gives me a credit when I returned something. Or, when you are at a store and return something to that store, you get a credit. Please do not confuse what you normally know with accounting as they do have different meanings.

A graduate of ours once shared this video she found on YouTube about debits and credits. It is sort of catchy and I hope you find that interesting.

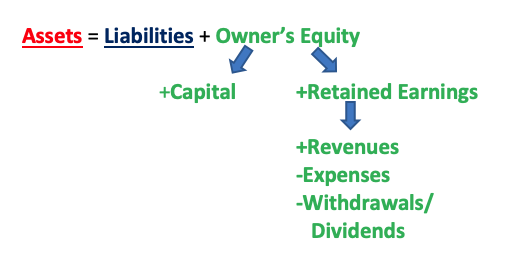

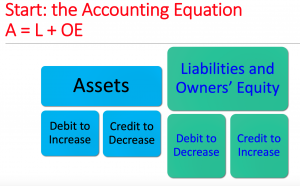

Recalling Debit is the left and Credit is the right, we will start with the accounting equation of A = L + OE and see how debiting and crediting accounts will affect them. Debit is not always adding or increasing and credit is not always subtracting or decreasing – it depends on the account. You may remember from Module 1 that the extended accounting equation looks like this:

So, let’s start with the first account type – asset. For assets, debit means increase, and credit means decrease. Now, liabilities and OE are on the other side of the accounting equation. So, while assets behave one way, logic will dictate that liabilities and owner’s equity will behave the opposite as they are on the opposite side of the equation. Therefore, for liabilities and owner’s equity accounts, debit means decrease and credit means increase.

Key Takeaways: Debits and Credits of A, L and OE

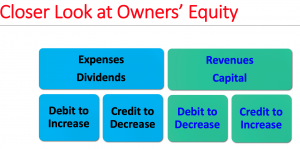

Please also notice from the diagram of the extended accounting equation that OE is made up of capital and retained earnings. And, retained earnings is further divided into revenues, expenses, and withdrawal/dividends. So how are all these accounts affected by debits and credits? If you look under owner’s equity, capital and revenues increase OE. If you earn more money in revenues, your OE increases; and if you invest more money in capital in your business, your OE increases as well. Thus, capital and revenues behave just as OE – debit to decrease, credit to increase.

On the other hand, expenses and withdrawals or dividends decrease OE. Owner’s Equity or OE is your claim to your business. As you paid expenses, you have less money in the business and the claim to your business decreases. This is the same for withdrawals or dividends. When money is taken out of the business to pay to owners as withdrawals or dividends, the claim that the owners have to the business of course will be less. So, expenses and withdrawals or dividends go against OE – and thus they behave like assets, which are opposite to OE. Therefore, for expenses and withdrawals/dividends – debit to increase, credit to decrease.

Key Takeaways: Debits and Credits for Capital, Revenues, Expenses and Dividends (Withdrawals)

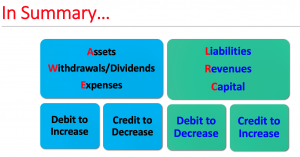

In summary, Assets, Withdrawals/dividends, and Expenses – increase with debit, decrease with credit. And, Liabilities, Revenues, and Capital – increase with credit, decrease with debit.

People come up with different nemonic devices to help them to remember things. For this, AWE spell awe! While there are a lot of “AWEsome” places on a college campus, the most awesome place I can think of is your Learning Resource Center – LRC. So, if you remember AWE and LRC, you now know how to increase all the accounts!

Let’s try this:

For the AWEsome accounts (assets, withdrawals/dividends and expenses), we debit to increase. For the LRC accounts (liabilities, revenues, and capital), we credit to increase!! Guess what? You got it! To decrease them, you just do the opposite. So, for the AWEsome accounts (assets, withdrawals and expenses), we credit to decrease. For the LRC accounts, we debit to decrease!!

Key Takeaways: Effects of Debits and Credits to ALL Accounts

For example, in the Julia Jansen problem, when Julia invested $8,000 in the business, her cash account (an asset) increased by $8,000. An increase in asset is a debit. But we also learned that for every debit there is a corresponding credit, so while we debit cash, we should at the time credit common stock. And, crediting common stock is increasing common stock as common stock is an owner’s equity account. So, in this case, we complete the analysis of the transaction by debiting cash $8,000, crediting common stock $8,000. Let’s look at a few more examples. As you are practicing all these examples, you will also begin to learn more accounts, their names, their type (A, W, E, L, R, C). You will not use OE as much as you are now splitting OE in to Withdrawals/Dividends (W), Expenses (E), Revenues (R), and Capital or Common Stock (C).

Examples: Debits and Credits – Transaction Analysis

- Jan 1 – Investment of $10,000 cash by owners as capital

- Jan 2 – Purchase $50 of office supplies

- Jan 2 – Bought food inventory of $450 on account

- Jan 2 – Purchase kitchen equipment of $5,000. Paid $1,000 in cash and obtain a note for the remainder

- Jan 3 – Paid monthly rent

- Jan 5 – Hired catering staff

- Jan 6 – Bought food inventory of $1,000

- Jan 7 – Catered first event and received $2,000

- Jan 15 – Catered an event and billed client for $1,500

- Jan 15 – Paid hourly catering staff $395

- Jan 25 – Received payment from the Jan 15 event

- Jan 31 – Owner withdrew $100

For each of the above event, note the accounts that need to be debited and credited.

Answer:

1. Jan 1 – Investment of $10,000 cash by owners as capital

(debit cash $10,000; credit capital $10,000)

Cash, an asset, increased, therefore debit; capital, part of OE, increased, therefore credit

2. Jan 2 – Purchase $50 of office supplies

(debit office supplies $50; credit cash $50)

Office supplies, an asset, increased, therefore debit; cash, an asset, decreased, therefore credit

When it is not mentioned that things are purchased on credit, that means we paid cash

3. Jan 2 – Bought food inventory of $450 on account

(debit food inventory $450; credit accounts payable $450)

Food inventory, an asset, increased, therefore debit; accounts payable, a liability, increased, therefore credit

Accounts payable is what we owe and we need to pay back later, that is why it is called “payable”; accounts receivable on the other hand is what our customers owe us, and we will receive from them later, that is why it is called “receivable”

4. Jan 2 – Purchase kitchen equipment of $5,000. Paid $1,000 in cash and obtain a note for the remainder

(debit kitchen equipment $5,000; credit cash $1,000, credit notes payable $4,000)

Kitchen equipment, an asset, increased, therefore debit; cash, an asset, decreased, therefore credit; and notes payable, a liability, increased, therefore credit.

When we signed a note or obtained a note, this means we borrowed money from a financial institution, normally a bank. This is why when you borrow money to buy your car you call that your car “note”. And since we need to pay it back later, it is called “payable” – thus “notes payable”

5. Jan 3 – Paid monthly rent of $750

(debit rent expense $750; credit cash $750)

Rent expense, an expense, increased, therefore debit; cash, an asset, decreased, therefore credit

All expense accounts will have the word expense, such as wages expense, salary expense, rent expense, etc. And, when you pay for any expense, cash will decrease. Thus, in paying any expense with cash, the expense account (wages expense, rent expense, et.c) will always be debited, and cash will always be credited

6. Jan 5 – Hired catering staff

(This is NOT a transaction. You just hired the staff member and he or she has not worked yet)

7. Jan 6 – Bought food inventory of $1,000

(debit food inventory $1,000; credit cash $1,000)

Food inventory, an asset, increased, therefore debit; cash, an asset, decreased, therefore credit

As no credit was mentioned, cash is paid. You have more food, so food inventory, an asset, increased with debit. You have less cash, so cash, an asset, decreased, and therefore is a credit

8. Jan 7 – Catered first event and received $2,000

(debit cash $2,000; credit food revenues $2,000)

Cash, an asset, increased, therefore debit; revenues, part of OE, increased, therefore credit

Anytime you make a sale, you collect revenue and therefore revenue is always credited. The debit depends on if you are paid the same day or if you bill your client. In this one, you received cash, so you debit cash. If you did not received cash and you billed the client, then, the debit will go to accounts receivable

9. Jan 15 – Catered an event and billed client for $1,500

(debit accounts receivable $1,500; credit revenues $1,500)

Accounts receivable, an asset, increased, therefore debit; revenues (part of OE), increased, therefore credit

In this one, you did not receive the cash on the same day. So therefore you use the account called accounts receivable denoting that you will receive the money later. However, the credit is the same as #8. You have earned the revenue. According to the revenue recognition principle in Module 2, you recognize revenue when it is earned, not when it is collected in cash. So, you have to credit revenue.

10. Jan 15 – Paid hourly catering staff $395

(debit wages expense $395; credit cash $395)

Wages expense, an expense, increased, therefore debit; cash, an asset, decreased, therefore credit

All expense accounts will have the word expense, such as wages expense, salary expense, rent expense, etc.

11. Jan 25 – Received payment from the Jan 15 event

(debit cash $1,500; credit accounts receivable $1,500)

Cash, an asset, increased, therefore debit; accounts receivable, an asset, decreased, therefore credit

Now, you have collected what is owed to you; so you have more cash but you will now have less accounts receivable since the money has been collected and is not owed to you any longer

12. Jan 31 – Owner withdrew $100

(debit withdrawal $100; credit cash $100)

Withdrawal, part of OE, increased, therefore debit; cash, an asset, decreased, therefore credit

Anytime an owner takes money out from the business or a corporation, that is withdrawals or dividends. Thus, the withdrawals or dividends account increases, therefore the account is debited. Cash is paid out, so there is less cash, and therefore cash is credited

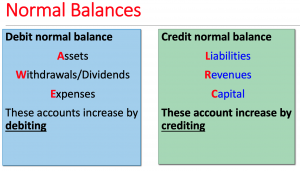

It is also important to note that how you increase an account is also known as the normal balance of the account. Therefore, the normal balance of assets, withdrawals/dividend, and expenses are DEBITS and the normal balance of liabilities, capital, and revenues are CREDITS.

Key Takeaways: Normal Balances of Accounts

Journalizing

After you have analyzed your transactions, you have completed Step 1 of the accounting cycle. The recording process of accounting takes care of Steps 2 and 3 of the accounting cycle which are journalizing and posting. Analyzing your transactions, determining the accounts affected, whether they should be debited or credited, what the amounts should be, are the difficult parts in accounting. Once the analysis is done in Step 1, everything from now on is simple logic. If you go step by step, you will not go wrong.

Journalizing is the second step in accounting cycle. All this means is to put all the information from the analysis you have just completed into a JOURNAL. The journal is also called the original book of entry as this is the first place where the accounting information is put onto paper and recorded. Journal entries are done chronologically. To journalize any transaction, you need to use the correct account titles and this process include:

- The date of the transaction – the date is always entered first. And to be consistent, if you use Jan 1, then use Jan 2 or Jan 15 and not 1/2 or 1-15.

- Accounts & amounts to be debited/credited – always enter the debited account first, flushed left to the margin; then enter the credited account, indented. If there are two debits and one credits, then entered both debited accounts first, both flushed left to the margin before entering the credited account

- Brief explanation of the transaction

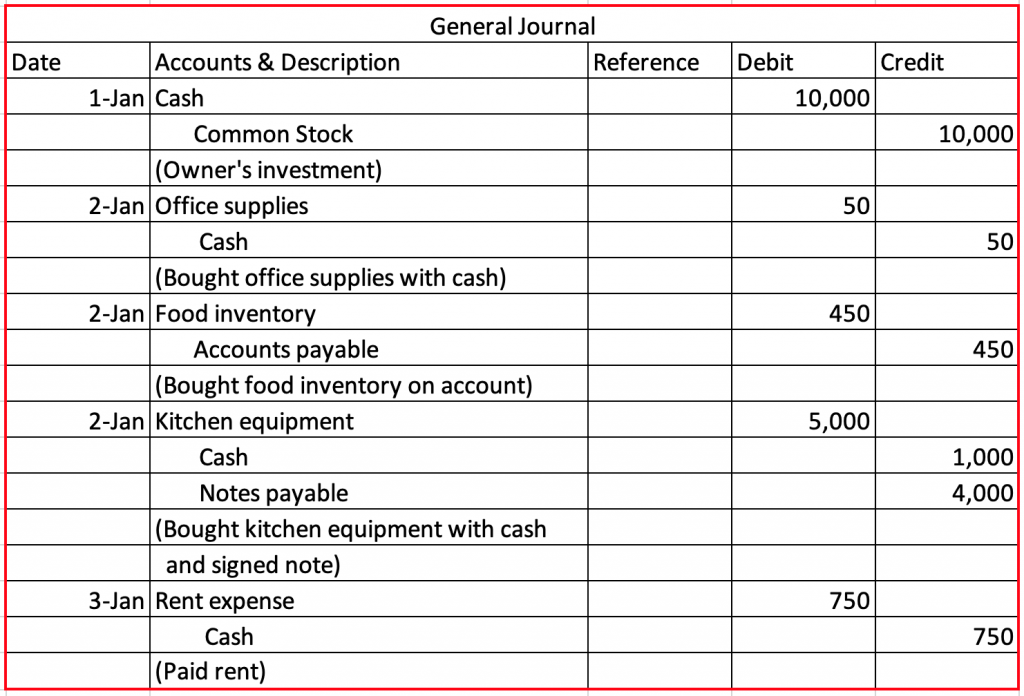

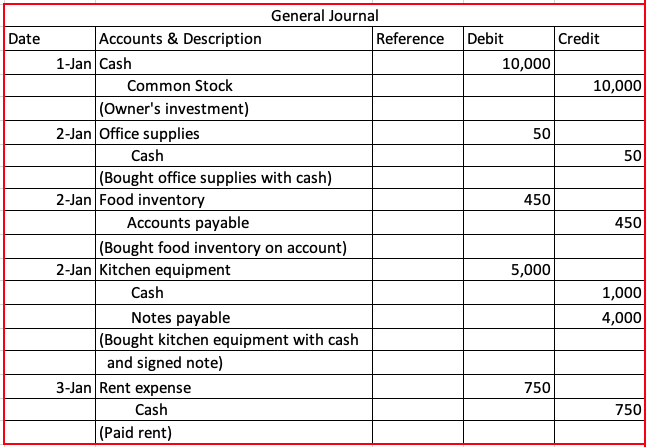

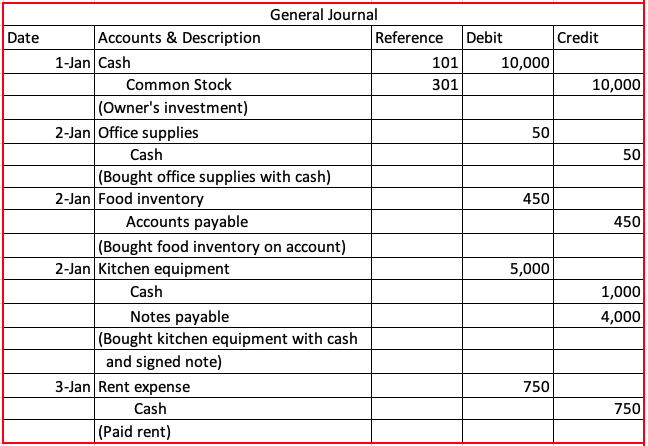

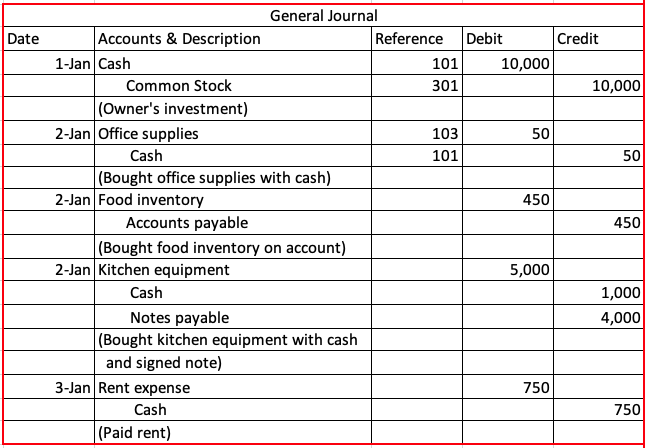

For most transactions that involve two accounts, they are known as simple entries. For transactions that involve three or more accounts, they are known as compound entries. Some examples of journal entries that correspond with the transaction analysis above can be found below. Note that the Reference or “Ref” column is now empty and it should be as such until you complete the posting step. In other words, when this column is empty, it indicates that the information has not been posted to the ledger as yet.

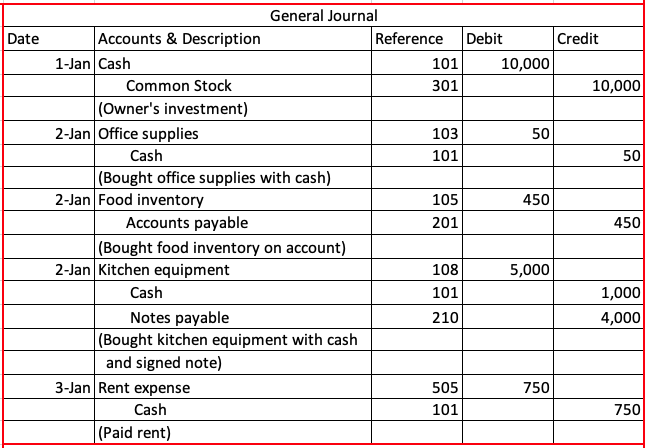

Examples: Journal Entry

- Jan 1 – Investment of $10,000 cash by owners as capital

- Jan 2 – Purchase $50 of office supplies

- Jan 2 – Bought food inventory of $450 on account

- Jan 2 – Purchase kitchen equipment of $5,000. Paid $1,000 in cash and obtain a note for the remainder

- Jan 3 – Paid monthly rent

Posting

After the transactions have been entered in the journal, the next step in the accounting cycle is posting. Posting means transferring the information from the journal to the ledger. The ledger or the general ledger contains all the accounts, meaning all the assets, liabilities, and stockholders’ equity accounts (A, L, C, W, R, E).

You may wonder why this is needed since we just recorded everything. Think about this – all we have now are all our transactions, all debits and credits, in a chronological order. This is very good in that if you want to know what happened on a certain day, as you can go to that specific date in the journal and you will find the answer. But if you want to know if you have paid an invoice, or if a client has paid you, or if you have paid your employees, and you do not know the date, this can be difficult. What if you want to know exactly how much cash you have in the business? What are you to do? Would you go and find all the journal entries that have cash and then add and subtract all of them? There has to be a better way – hence posting!

Again, posting is simply transferring the information from the journal to the ledger. And, the ledger is a list of all your accounts in a certain order – A, L, C, W, R, E. By the way, this is also the order the accounts appear on a trial balance (next step of the accounting cycle) and the balance sheet. So, what is included in posting? In posting you are taking the information piece by piece and place them in each account in the ledger. The accounts in the ledger follows the order of what is called a “chart of accounts”. Each business will set up its own chart of accounts depending on what accounts are used in that business. A small business may only have a hundred or so accounts and a multi-national hotel company may have thousands of accounts. However, all accounts can be classified into either A, L, C, W, R, or E. All accounts will also have an account number to keep things in order. As such, most assets start with “1”, liabilities with “2”, capital and withdrawals/dividends as “3”, revenues as “4” and sometimes “5”, and expenses are normally “6” through “9”. The account numbers may be 3 or 4 digits. Since each business uses different numbers, you don’t need to worry about memorizing the numbers given here. But, do note the first number of each group of account. Below is a sample chart of accounts.

Examples: Chart of Accounts

On the left side of the account name, there will be a 3 or 4 or 5 digit number (depending on the business), which is called the reference number (a way to find/identify/classify your accounts).

| Assets (reference numbers start with “1”; listed in order of liquidity)

101 Cash 104 Accounts Receivable 107 Supplies 109 Inventories 110 Prepaid Insurance 111 Prepaid Rent 112 Furniture 115 Office Equipment 116 Accumulated Depreciation (contra asset)

Liabilities (reference number starts with “2”) 203 Notes Payable 204 Accounts Payable 206 Current portion of long term debt 207 Unearned Revenue 208 Salaries Payable 210 Interest Payable 258 Taxes Payable

Stockholders’ Equity (reference number starts with “3”) 304 Common Stock 315 Retained Earnings 317 Dividends 319 Income Summary (you will see this in Module 5) |

Revenues (reference number starts with “4”)

400 Service Revenue 408 Food Revenue 412 Beverage Revenue 416 Spa Revenue 421 Golf Course Revenue

Expenses (reference for labor cost/expense generally starts with “6”; all other start with “7”/”8”/”9”) 605 Salary expense 609 Wages expense 619 Employee benefits 704 Depreciation expense 733 Insurance expense 735 Utilities expense 741 Rent expense 756 Interest expense 784 Internet expense 800 Cost of food sold 801 Cost of beverage sold |

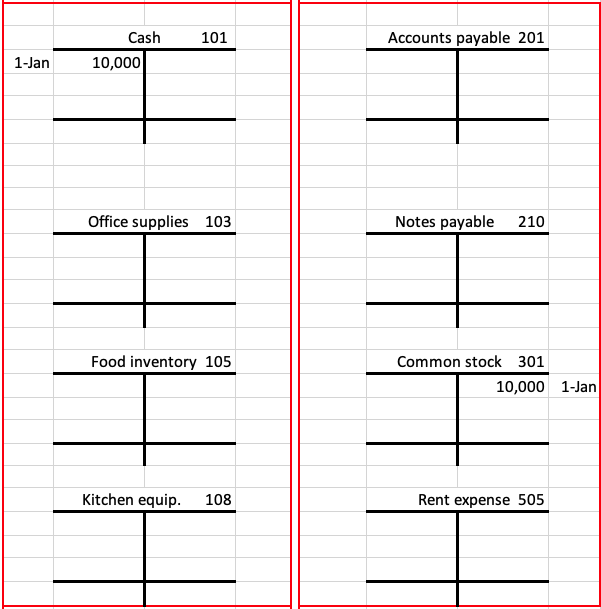

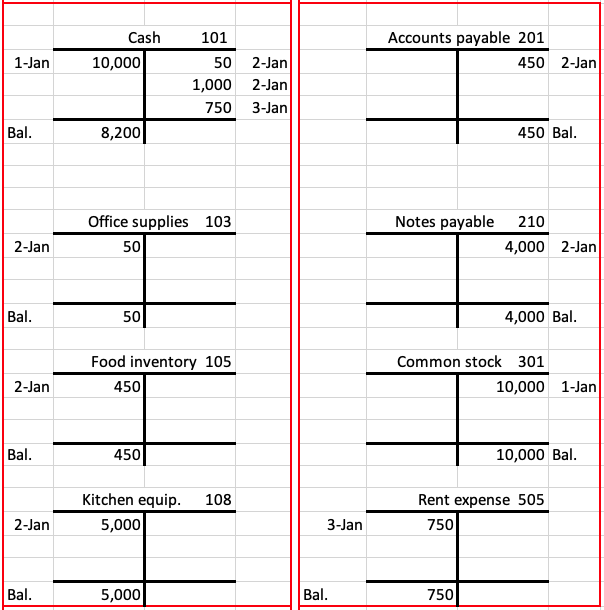

Using T-accounts, the five journal entries are now posted in the accounts in the ledger. The steps for posting are as follow:

- transfer the date to the ledger accounts

- transfer the amounts, debit or credit to the ledger accounts

- transfer the corresponding ledger account numbers back to the reference column of the journal

- calculate the totals of each account

Examples: Posting

Journal entries complete. Next step – posting.

Posting dates and amounts with debit to cash, credit to common stock. Account numbers are then transferred to the reference column of the journal.

Posting dates and amounts with debit to office supplies, credit to cash. Account numbers are then transferred to the reference column of the journal.

Posting complete with reference column in the journal all filled in and each account in the ledger has a balance.

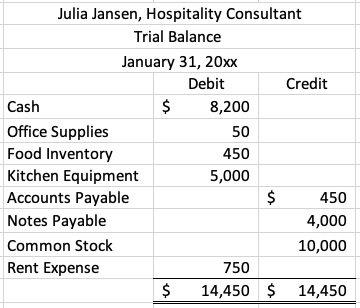

The Trial Balance

After all the postings are complete, each account will have its updated balance. This is the time to pause, where you will make sure that all debits and credits are correct, before we move on to the. Thus, Step 4 of the accounting cycle, after posting, is the trial balance. Below are the characteristics and uses of a trial balance:

- To list all accounts and their respective balances at a specific date

- Always in order of assets (in order of liquidity), liabilities, capital, withdrawals/dividends, revenues, and expenses

- Dollar signs go on the first of each debit and credit & by each total/answer

- The trial balance, like the balance sheet, is a dated statement, reporting the balances of each account on a specific date

- Just like any statement, it also has a three-line title

- Is used to prove/check/verify that the total debits equal total credits after posting

- Limitations – Have all the transactions been recorded? Was the debt and/or credit posted to the wrong account? – Thus a trial balance DOES NOT eliminate all mistakes.

Examples: A Trial Balance

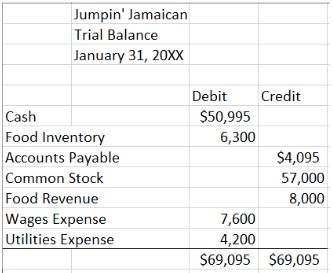

To continue the example we used earlier, if those 5 transactions were the only transactions happened in January, then on January 31, the trial balance will be as follow:

Take some time to watch the summary videos posted on Blackboard under Module 3. They go over journalizing, posting, and the trial balance again in the previous sections. They are definitely very helpful as a review! Then try your hands on this example below.

Examples: Journalizing, Posting, Trial Balance

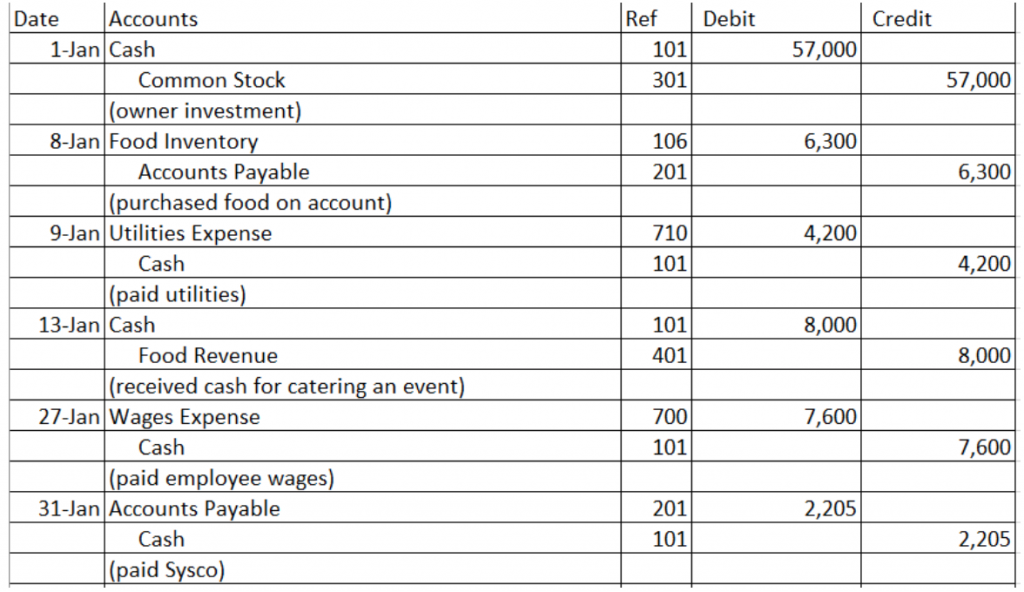

Jackson just opened his first restaurant, Jumpin’ Jamaican. During the first month of operations of the business, the following events and transactions occurred:

-

- January 1 Invested $57,000 cash in exchange for common stock

- January 8 Purchased $6,300 of food on account from Sysco

- January 9 Paid utilities of $4,200 for the month

- January 13 Received $8,000 in for catering an event

- January 27 Paid employee wages of $7,600 for the month

- January 31 Paid 35% of balance due to Sysco

The company uses the following chart of accounts: No.101 Cash, No.106 Food Inventory, No.201 Accounts Payable, No.301 Common Stock, No.401 Food Revenue, No.700 Wages Expense, and No.710 Utilities Expense.

-

- Journalize the transactions

- Post to the ledger accounts

- Prepare a trial balance on January 31

Answer:

-

- Journalize the transactions

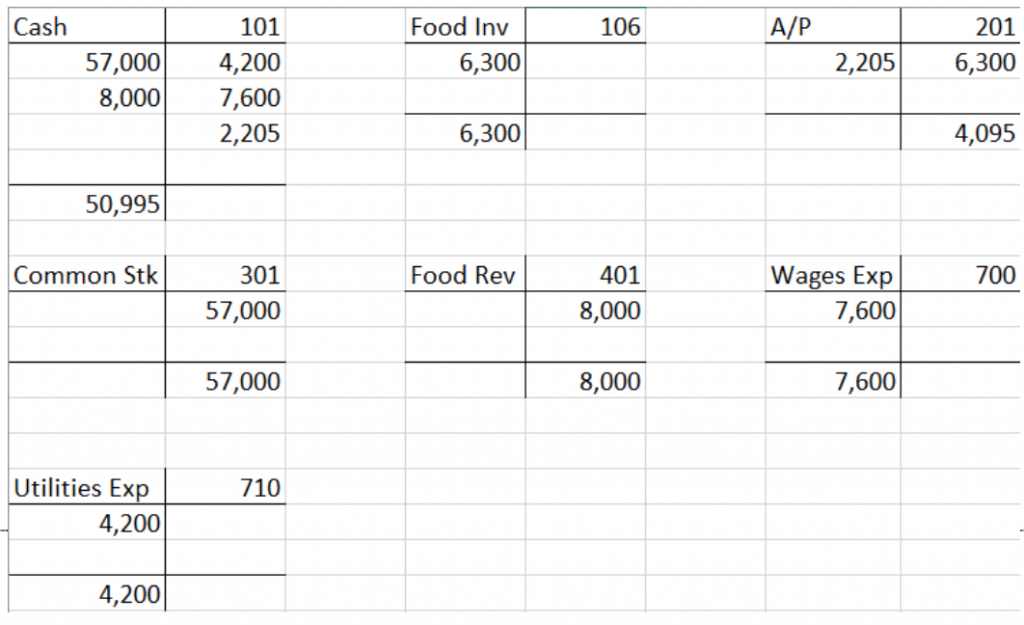

2. Post to the ledger accounts

3. Prepare a trial balance on January 31