Chapter 8: Paleoenvironments

The 2nd edition is now available! Click here.

Learning Objectives

The goals of this chapter are to:

- Categorize fossil assemblages to determine their habitats

- Develop connections between modern and ancient paleoenvironments

- Evaluate paleoenvironments through time and space

8.1 Introduction

Some geologists use fossils to determine stratigraphy and correlate stratigraphic sequences. Others prefer to study paleoecology to determine ancient habitats where both plants and animals co-existed. This avenue leads to discoveries about past climate, predator-prey relationships, and even ocean depth. Using this information, artists create reconstructed paleoenvironments (Figure 8.1) to display these ancient habitats.

Remember, fossils are not just exciting curiosities but were once living organisms that reproduced, ate each other, and interacted with their environment just like we do. A fossil’s paleoecology depends on many factors of their paleoenvironment. These include physical conditions, such as temperature, light, water depth, and energy (calm vs. turbulent), and chemical conditions, such as salinity, pH, oxygen, and toxic chemicals. Some animals will thrive if these variables change, and others will die off. Have you ever been to the beach and seen large piles of seaweed? They came from the middle of the ocean and were brought to shore as ocean currents and winds changed. Some organisms can survive environmental change, such as oysters that can live in both salty and freshwater. Fossils hold the key to determining what the paleoenvironment was like. This ability to reconstruct a fossil’s paleoenvironment is one of the most valuable tools that a paleontologist has to offer to broader fields of geology.

Understanding every detail of how a fossil lived is not necessary to help you use fossils to interpret an ancient environment in the rock record. For example, suppose you know that a phylum is exclusively marine or exclusively terrestrial. In that case, this can easily change your interpretation of an otherwise dull sedimentary layer. This is just the beginning of using fossils to determine the paleoenvironment; if you know how it lived, you can determine where it lived.

For any fossil group, ask yourself some basic questions such as the type of the skeleton, its body plan (symmetry), its habitat, and how it fed and behaved. You might find these are hard to determine with fossils but give it a try. Table 8.1 is a list of characteristics that you can use for determining its paleoenvironment:

Where is the skeleton relative to the tissue, as this can be internal, external, or none? Also, look at the number of parts in the skeleton and its construction. This can be either a single element or multiple elements like bivalves (two-part), multivalve (range of 3 to ~15 parts), plates, ossicles or bones (many parts from 10’s to 100’s), or spicules (very many small parts numbering up to 1,000’s).

Symmetry is similar to what you described in the last chapter but now consider how it relates to how the organism lived. Bilateral symmetry means that both locomotory and sensory organs can be placed efficiently. In contrast, organisms with radial symmetry tend to be slow or immobile (sessile). They also respond to stimuli from all directions. Organisms with spherical symmetry will live in open water. Finally, those with no symmetry are typically immobile (sessile).

| Skeleton Type | Number of Parts in Skeleton | Symmetry | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Internal | External | Single Element | Multi-Element | Plates or bones | Bilateral | Radial |

| Ammonite | X | X | X | ||||

| Belemnite | X | X | X | ||||

| Bivalve | X | X | X | ||||

| Blastoid | X | X | X | ||||

| Brachiopod | X | X | X | ||||

| Bryozoa | X | X | X | ||||

| Crinoid | X | X | X | ||||

| Echinoid | X | X | X | ||||

| Gastropod | X | X | X | ||||

| Graptolite | X | X | X | ||||

| Rugosa | X | X | X* | ||||

| Scleractinia | X | X | X* | ||||

| Tabulata | X | X | X* | ||||

| Trilobite | X | X | X | ||||

8.2 Marine Paleoenvironments

Most of the fossils you have studied are marine, but remember there are many other environments in the terrestrial, transitional, and marine realms (Table 8.2). Within these environments, organisms can have different modes of life, including not moving (sessile), attached by cement to the bottom, or unattached and able to move (motile) (Table 8.3). Some also categorize organisms as benthic and planktonic. Benthic organisms live at the bottom of the ocean on or in the sediment, and planktonic organisms float or swim.

| Habitat | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Terrestrial | Transitional | Marine |

| Ammonite | X | ||

| Belemnite | X | ||

| Bivalve | X | X | |

| Blastoid | X | ||

| Brachiopod | X | ||

| Bryozoa | X | ||

| Crinoid | X | ||

| Echinoid | X | ||

| Gastropod | X | X | X |

| Graptolite | X | ||

| Rugosa | X | ||

| Scleractinia | X | ||

| Tabulata | X | ||

| Trilobite | X | ||

The way an organism feeds is important for determining its role in the paleoenvironment (Table 8.3). Does it eat by suspension-feeding as it collects small particles from the water column? Or perhaps it eats by deposit-feeding and ingesting sediment to get nutrients. Is it an herbivore that only eats plant material, a carnivore that captures and kills its prey, an omnivore that eats both plants and animals, or a scavenger that only eats dead material? One fascinating debate among paleontologists is whether Tyrannosaurus rex was a carnivore or scavenger. Ask yourself: if it was a carnivore, how could it catch its prey with such tiny forearms? Whereas if it was a scavenger, having small arms might be an advantage for just using its large teeth to tear apart the dead meat. The final question is to determine if the organism lived a solitary life or in a colony with others of its own kind. If you can answer some or all of these questions from your observations, you’ll be able to address more fascinating aspects of ancient life.

| Mobility | Feeding | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Attached | Mobile | Suspension | Deposit (Sediment) | Herbivore | Carnivore | Scavenger |

| Ammonite | X | ||||||

| Belemnite | X | X | |||||

| Bivalve | X | X | |||||

| Blastoid | X | X | |||||

| Brachiopod | X | ||||||

| Bryozoa | X | X | |||||

| Crinoid | X | X | |||||

| Echinoid | X | X | X | ||||

| Gastropod | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Graptolite | X | X | |||||

| Rugosa | X | X | |||||

| Scleractinia | X | X | |||||

| Tabulata | X | X | |||||

| Trilobite | X | X | |||||

8.3 Continental Paleoenvironments

Depending on the continental paleoenvironment, these can be just as fossiliferous as marine environments. For example, swamps and lagoons can have a wide variety of fish, plant, and insect fossils. In continental paleoenvironments, you commonly do not find index fossils as these are not as widespread. Think how quickly the environment can change during a drive through the countryside. Instead these paleoenvironments can record biodiversity and can be used for paleobehavioral analysis. Often these are the fossils more commonly known to the general public as they catch our imagination. What child doesn’t know the name of common dinosaurs or ice age mammals?

Exercise 8.1 – Marine Paleoenvironments

First, review these summaries of the characteristics of Bryozoans and Echinoidea that can be used to determine their paleoenvironments:

Bryozoans: External skeleton. Individuals (zooids) are bilaterally symmetric, but colonies are typically asymmetric. Marine immobile (sessile), typically attached to the substrate, benthic, suspension feeders, and lives in colonies.

Echinoidea: Internal skeleton. Radial (5-fold or pentamerous) symmetry. Marine benthic scavenger or deposit feeder, mobile, and solitary lifestyle.

Using these descriptions as a guide along with your observations, Table 8.1, and material from Chapter 7, characterize a coral (Rugosa) and brachiopod.

- Summarize the characteristics that will be useful to determine the paleoenvironment of a Rugosa coral.

- Summarize the characteristics that will be useful to determine the paleoenvironment of a brachiopod.

- Next, speculate on the paleoenvironment for all four (bryozoans, echinoids, rugosa, and brachiopod) of these organisms. Would all of these four organisms live in the same paleoenvironment?

- Both bryozoans and echinoids lived throughout the fossil record and thus are not good index fossils. In contrast, rugosa and brachiopods are both more limited in their age range. Using the diversity plots in Chapter 7, what age could a paleoenvironment be if it had both of these fossils?

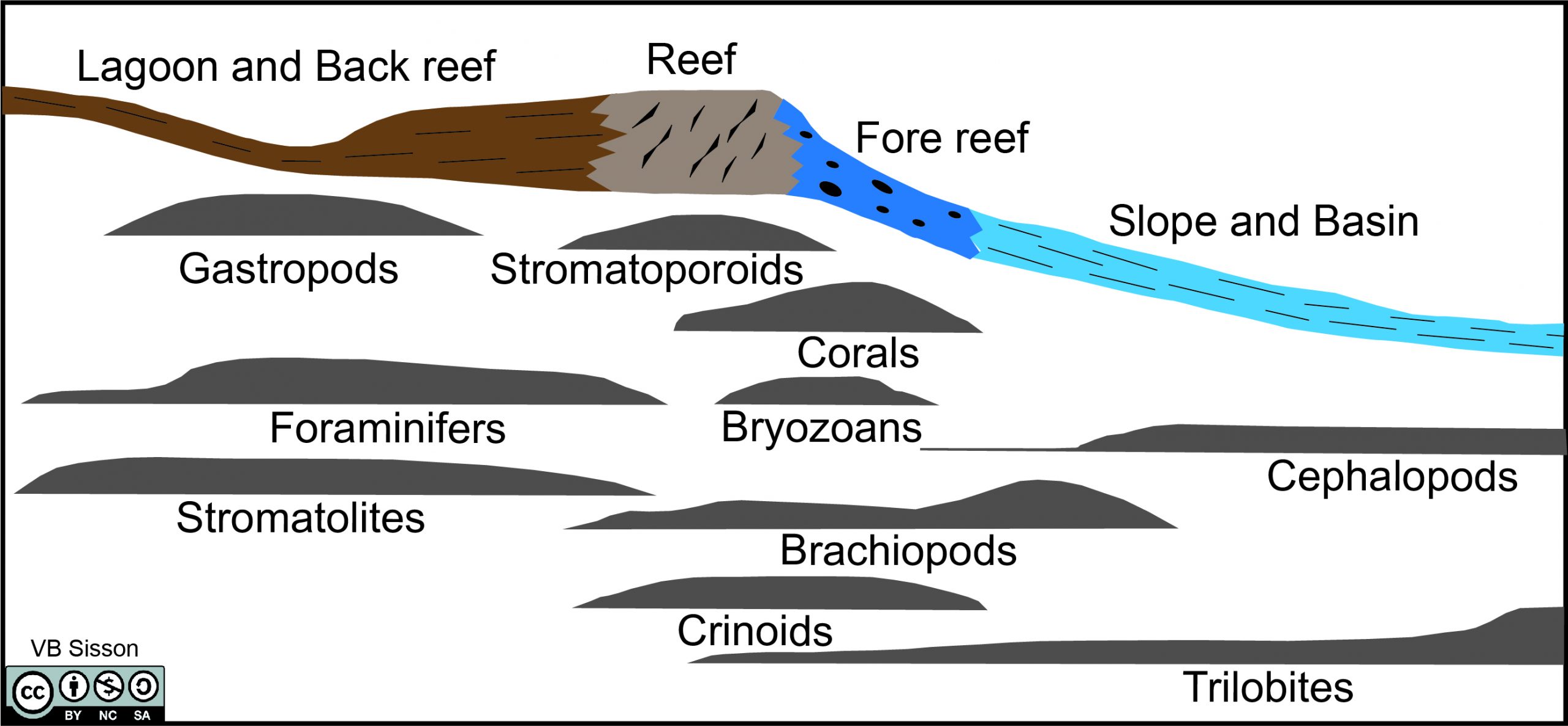

Exercise 8.2 – Devonian Reef

Head to the PaleoDB Navigator. A large map of the world should open with many colored circles. The circles represent locations where fossils have been discovered, and the color of the circle corresponds to the geologic timescale at the bottom of the page. You can click through the different time periods to see where fossils of that age have been discovered. On the right side, there is a list of the most abundant fossil groups based on the time period you have selected on your map view. For example, you could zoom in on fossils found in South America from the Ordovician Period. The menu on the right will update with what fossils are found on your map for that period. Depending on your zoom level, you may see that the Trilobita Class is the most abundant, or you may see it broken down into several orders of Trilobita with the Asaphida Order as the most abundant. If there is lower diversity of fossils in your map view and time period, you will see the classification broken down to lower levels. You may find you need to Google some of the names to figure out what phylum, class, or order they belong to. You can clear whatever filters you select on the lower left side of the page.

- In the PaleobioDB Navigator, set your time period to Devonian and zoom in on New York State. What is the most common group of Devonian fossils found in New York? Remember, you may need to search more technical taxonomic names to determine which fossils you’re looking at (I’m talking about you, Rhynchonellata and Strophomenata).

- What are some other organisms that are present?

- What type of environments are most of these organisms found in?

- Compare the locations of gastropods and cephalopods. You can do this by clicking on the classes on the right-hand menu. Look at the two locations of these fossils compared to each other. You may find it easier to have two browser windows open for this. Based on the locations from the navigator and the typical locations of fossils around a Devonian reef, what direction was the coastline located?

- Remove any organism filter and now look at the distribution of all fossils throughout the Devonian in New York. Click on “E”, “M”, and “L” under Devonian to look at the distribution from early to middle to late Devonian. Was sea level rising or falling in this region during the Devonian (you already know which way the coastline was based on your previous answer)?

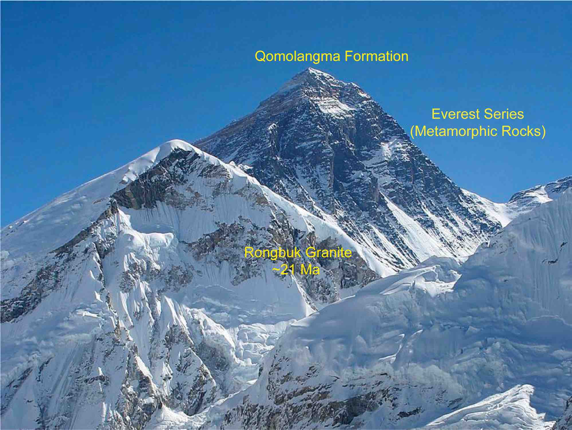

Exercise 8.3 – Himalayan Mountains

- Figure 8.3 shows the tallest peak on Earth, Mount Everest, at 8,848 m (29,029 ft) (Tibetan name Qomolangma). It has a layer of unaltered limestone from the Ordovician at its summit. What does this tell you about the environment of Mt. Everest during that time?

- Using the PaleoDB navigator, look at the distribution of fossils for the Himalaya Mountains, particularly near the Nepal/China border. During which two geologic time periods were fossils most abundant?

- What were the most abundant organisms for each of those periods? The pane on the right side tells you the percentage of each organism found in your current map view. You may need to search the technical taxonomic name to learn which organism it is.

- Based on the changes in fossils over the time periods, determine whether sea level was rising, falling, or constant. Be sure to explain your answer.

- Critical thinking: Does your sea-level interpretation match the global sea level record from Figure 5.21? Explain your answer.

8.4 Fossils and Paleoenvironments in Movies

We all know that Hollywood stretches the truth (or outright makes it up) when depicting science in movies. Perhaps the most famous movie depicting fossils and paleoenvironments is the Jurassic Park series. For example, in the original movie from 1993, there is a scene where a Tyrannosaurus rex chases a Jeep at over 60 mph. At the time of production, some paleontologists thought T. rex could only run at a maximum speed of about 45 mph. However, we now know that T. rex didn’t have the hip structure to support running and was more of a brisk walker. So, you could probably outrun a T. rex.

Exercise 8.4 – Jurassic Park

Using the PaleobioDB Navigator, look up “Dinosauria” (an unranked clade). A clade is a group of organisms that share a common ancestor, and cladistics is a way to classify organisms based on common characteristics. You’ll notice that one of the groups in the Dinosauria clad is Aves, which is the class comprising birds. Yes, according to cladistics and taxonomic rankings, dinosaurs and birds are related.

- During which geologic time periods were Dinosauria most abundant (excluding Aves)?

- Which one of those time periods were Dinosaurs (not Aves) most abundant?

- The movie franchise Jurassic Park showcases several different dinosaurs. The table below contains the seven dinosaur genera shown in the original film from 1993. Complete the table below with what geologic time periods these dinosaurs actually lived and what their preferred habitat was (use Google to search for the “[genera] habitat.” Remember, the movie depicted all of these dinosaurs living in a tropical climate.

Table 8.4 – Worksheet for Exercise 8.4. Genera Geologic Time Period Preferred Habitat Tyrannosaurus Brachiosaurus Triceratops Velociraptor* Dilophosaurus Gallimimus Parasaurolophus *In the movies and book Velociraptor was based on a similar dinosaur, called Deinonychus, in almost every detail, and that only the name had been changed to be more dramatic.

- Does Jurassic Park seem like a fitting name based on when these dinosaurs lived? Why or why not?

Additional Information

Exercise Contributions

Daniel Hauptvogel and Virginia Sisson

Exercise 8.1 was inspired by an exercise on Life Mode Characteristics by Steven J. Hageman at Appalachian State University

References

Barreda V.D., Cúneo N.R., Wilf P., Currano E.D., Scasso R.A., Brinkhuis H., 2012, Cretaceous/Paleogene Floral Turnover in Patagonia: Drop in Diversity, Low Extinction, and a Classopollis Spike. PLoS ONE 7(12): e52455. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052455

Corradini, C., Pondrelli, M., Corriga, M.G., Simonetto, L., Kido, E., Suttner, T.J., Spalletta, C., and Carta, N., (2012). Geology and stratigraphy of the Cason di Lanza area (Mount Zermula, Carnic Alps, Italy). Berichte des Institutes für Erdwissenschaften, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz. 17. 83-103.

Google Earth Locations

the natural home or environment of a plant or animal

an environment that prevailed at some time in the geologic past

either a a small piece of a invertebrate skeleton such as an echinoderm or a very small bone in the ear

part of the skeleton of a sponge that is a small needle-like structure made of calcite or silica

having the power of locomotion

a fossil used for both dating and correlating of strata in which it is found. These are typically organisms that lived for a short geologic time period

a group of organisms believed to have evolved from a common ancestor