1.1 Tech Is Everywhere

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Define information systems, management information systems.

- Understand the basic role of MIS in organizations.

- Appreciate the degree to which technology has permeated every management discipline.

- See that tech careers are varied, richly rewarding, and poised for continued growth.

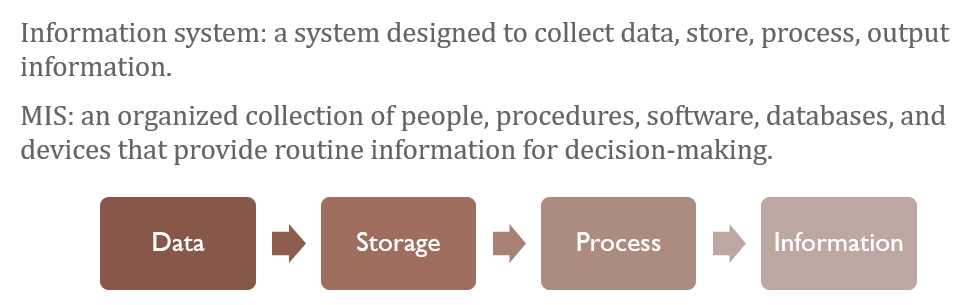

Information systems are historically defined as systems that allow us to take meaningless data, store them, then process, and output useful information at the end. Information systems are not new; they have been around throughout human history. For example, the spoken word: languages are millions of years old and allowed humans to communicate with one another synchronously, while they were in the same environment. The written word is thousands of years old and allowed peoples to send messages, write poetry, share laws, and other useful information to form societies. The printed word has allowed information to spread faster and with a far greater reach than other systems that preceded it since Johannes Gutenberg built his printing press. The digital revolution in the mid-twentieth century enables us all to store and process data into information at unprecedented speeds.

Ultimately, we take something that has little to no value on its own and we give it meaning within the context of our thinking, our business, our world.

Information systems can be manual or digital, paper-based or computerized, low tech and speed, or high tech and high speed. They can cost as little 99c in the shape of a cheap paper notebook or cost over $15 billion to develop, as IBM has spent on its sophisticated artificial intelligence system Watson.

Information systems are all around us to help us, businesses, and organizations make better decisions. We live in the age of Big Data, data that is so voluminous that we cannot store it in a single system, nor can we process it all. We all contribute to our global collective pile of data by updating our social media, buying anything and everything in stores and online, taking classes using Blackboard, even reading this book online. All of that data piles up very quickly and organizations can use information systems to make sure they understand why events occur, what products to develop further, and which lectures to tweak based on user behavior. Not all data gets processed, so the output of an information system will always be lower in volume than its input.

In the early 2000s, there was a lot of concern that tech jobs would be outsourced, leading many to conclude that tech skills carried less value and that workers with tech backgrounds had little to offer. Turns out this thinking was stunningly wrong. Tech jobs boomed, and as technology pervades all other management disciplines, tech skills are becoming more important, not less. Today, tech knowledge can be a key differentiator for the job seeker. It’s the worker without tech skills that needs to be concerned.

As we’ll present in-depth in a future chapter, there’s a principle called Moore’s Law that’s behind fast, cheap computing. And as computing gets both faster and cheaper, it gets “baked into” all sorts of products and shows up everywhere: in your pocket, in your vacuum, and on the radio frequency identification (RFID) tags that track your luggage at the airport.

There is also a type of Moore’s Law corollary that’s taking place with people, too. As technology becomes faster and cheaper and developments like open-source software, cloud computing, software as a service (SaaS), and outsourcing push technology costs even lower, tech skills are being embedded inside more and more job functions. What this means is that even if you’re not expecting to become the next Tech Titan, your career will definitely be shaped by the forces of technology. Make no mistake about it—there isn’t a single modern managerial discipline that isn’t being deeply and profoundly impacted by tech.

Finance

Many business school students who study finance aspire to careers in investment banking. Many i-bankers will work on IPOs, or initial public stock offerings. They will help value companies the first time these firms wish to sell their stock on the public markets. IPO markets need new firms, and the tech industry is a fertile ground that continually sprouts new businesses like no other. Other i-bankers will be involved in valuing merger and acquisition (M&A) deals, and tech firms are active in this space, too. Leading tech firms are flush with cash and constantly on the hunt for new firms to acquire. In the prior decade, Cisco bought forty-eight; IBM bought thirty-five, Microsoft bought thirty, Google bought eighteen firms (Source: VentureSource). And even in nontech industries, technology impacts nearly every endeavor as an opportunity catalyst or a disruptive wealth destroyer. The aspiring investment banker who doesn’t understand the role of technology in firms and industries can’t possibly provide an accurate guess at how much a company is worth.

Those in other finance careers will be lending to tech firms and evaluating the role of technology in firms in an investment portfolio. Most of you will want to consider tech’s role as part of your personal investments, and modern finance simply wouldn’t exist without tech. When someone arranges for a bridge to be built in Shanghai, those funds aren’t carried over in a suitcase—they’re digitally transferred from bank to bank. Forces of technology also blasted open the two-hundred-year-old floor trading mechanism of the New York Stock Exchange, in effect forcing the NYSE to sell shares in itself to finance the acquisition of technology-based trading platforms that were threatening to replace it. As another example of the importance of tech in finance, consider that Boston-based Fidelity Investments, one of the nation’s largest mutual fund firms, spends roughly $2.8 billion a year on technology. Tech isn’t a commodity for finance—it’s the discipline’s lifeblood.

Accounting

If you’re an accountant, your career is built on a foundation of technology. The numbers used by accountants are all recorded, stored, and reported by information systems, and the reliability of any audit is inherently tied to the reliability of the underlying technology. Increased regulation, such as the heavy executive penalties tied to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the United States, have ratcheted up the importance of making sure accountants (and executives) get their numbers right. Negligence could mean jail time. This means the link between accounting and tech have never been tighter, and the stakes for ensuring systems accuracy have never been higher.

Business students might also consider that while accounting firms regularly rank near the top of BusinessWeek’s “Best Places to Start Your Career” list, many of the careers at these firms are highly tech-centric. Every major accounting firm has spawned a tech-focused consulting practice, and in many cases, these firms have grown to be larger than the accounting services functions from which they sprang. Today, the tech-centric consulting division of Deloitte (one of the Big Four accounting firms) is larger than the firm’s audit, tax, and risk practices.

At the time of its spin-off, Accenture was larger than the accounting practice at former parent Arthur Andersen (Accenture executives are also grateful they split before Andersen’s collapse in the wake of the prior decade’s accounting scandals. See: Enron Scancal). Now, many accounting firms that had previously spun off technology practices are once again building up these functions, finding strong similarities between the skills of an auditor and skills needed in emerging disciplines such as information security and privacy.

Marketing

Technology has disrupted the marketing landscape, and as a result, the skill set needed by today’s marketers is radically different from what was leveraged by the prior generation. Online channels have provided a way to track and monitor consumer activities, and firms are leveraging this insight to understand how to get the right product to the right customer, through the right channel, with the right message, at the right price, at the right time. The success or failure of a campaign can often be immediately assessed based on online activity such as Web site visit patterns and whether a campaign results in an online purchase.

The ability to track customers, analyze campaign results, and modify tactics has amped up the return on investment of marketing dollars, with firms increasingly shifting spending from tough-to-track media such as print, radio, and television to the Web (Pontin 2009). New channels continue to emerge, with firms as diverse as Southwest Airlines, Starbucks, UPS, and Zara introducing apps for iPhones and Android devices. Cell phones can deliver location-based messages and services, and even allowing for cashless payment.

The rise of social media is also part of this blown-apart marketing landscape. Now all customers can leverage an enduring and permanent voice, capable of broadcasting word-of-mouth influence in ways that can benefit and harm a firm. Savvy firms are using social media to generate sales, improve their reputations, better serve customers, and innovate. Those who don’t understand this landscape risk being embarrassed, blindsided, and out of touch with their customers.

Search engine marketing (SEM), search engine optimization (SEO), customer relationship management (CRM), personalization systems, and a sensitivity to managing the delicate balance between gathering and leveraging data and respecting consumer privacy are all central components of the new marketing toolkit. And there’s no looking back—tech’s role in marketing will only grow in prominence.

Supply Chain, Sourcing, Operations

A firm’s operations management function is focused on producing goods and services, and operations students usually get the point that tech is the key to their future. Quality programs, process redesign, supply chain management, knowledge management systems, factory automation, and service operations are all tech-centric. These points are underscored in this book as we introduce several examples of how firms have designed fundamentally different ways of conducting business (and even entirely different industries), where value and competitive advantage are created through technology-enabled operations.

Management, Human Resources

Technology helps firms harness the untapped power of employees. Knowledge management systems (KMS) are morphing into social media technologies—social networks, wikis, and Twitter-style messaging systems that can accelerate the ability of a firm to quickly organize and leverage teams of experts. Human resources (HR) directors are using technology for employee training, screening, and evaluation. The accessibility of end-user technology means that every employee can reach the public, creating an imperative for firms to set policy on issues such as firm representation and disclosure and to continually monitor and enforce policies as well as capture and push out best practices. The successful HR manager recognizes that technology continually changes an organization’s required skill sets, as well as employee expectations.

The hiring and retention practices of the prior generation are also in flux. Recruiting hasn’t just moved online; it’s now grounded in information systems that scour databases for specific skill sets, allowing recruiters to cast a wider talent net than ever before. Job seekers are writing résumés with keywords in mind, aware that the first cut is likely made by a database search program, not a human being. The rise of professional social networks also puts added pressure on employee satisfaction and retention. Prior HR managers fiercely guarded employee directories for fear that a headhunter or competitive firm might raid top talent. Now the equivalent of a corporate directory can be easily pulled up via LinkedIn, a service complete with discrete messaging capabilities that can allow competitors to rifle-scope target your firm’s best and brightest. Thanks to technology, the firm that can’t keep employees happy, engaged, and feeling valued has never been more vulnerable.

The Law

And for those looking for careers in corporate law, many of the hottest areas involve technology. Intellectual property, patents, piracy, and privacy are all areas where activity has escalated dramatically in recent years. The number of U.S. patent applications waiting approval has tripled in the past decade, while China saw a threefold increase in patent applications in just five years (Schmid & Poston, 2009). Firms planning to leverage new inventions and business methods need legal teams with the skills to sleuth out whether a firm can legally do what it plans to. Others will need legal expertise to help them protect proprietary methods and content, as well as to help enforce claims in the home country and abroad.

Management Information Systems Careers

Management Information Systems as a major has consistently outperformed all other majors (See: Dr. Park’s data collection here for 2014-2018). While the job market goes through ebbs and flows, recent surveys have shown there to be more IT openings than in any field except health care1. Money magazine ranked tech jobs as two of the top five “Best Jobs in America.”2 BusinessWeek ranks consulting (which heavily hires tech grads) and technology as the second and third highest paying industries for recent college graduates (Gerdes, 2008, Parks 2019). Technology careers have actually ranked among the safest careers to have during an economic downturn (Kaneshige, 2009). And Fortune’s ranks of the “Best Companies to Work For” is full of technology firms, too3.

Students studying technology can leverage skills in ways that range from the highly technical to those that emphasize a tech-centric use of other skills. Opportunities for programmers abound, particularly for those versed in new technologies, but there are also roles for experts in areas such as user-interface design (who work to make sure systems are easy to use), process design (who leverage technology to make firms more efficient), and strategy (who specialize in technology for competitive advantage). Nearly every large organization has its own information systems department. That group not only ensures that systems get built and keep running but also increasingly takes on strategic roles targeted at proposing solutions for how technology can give the firm a competitive edge. Career paths allow for developing expertise in a particular technology (e.g., business intelligence analyst, database administrator, social media manager), while project management careers leverage skills in taking projects from conception through deployment.

Even in consulting firms, careers range from hard-core programmers who “build stuff” to analysts who do no programming but might work identifying problems and developing a solutions blueprint that is then turned over to another team to code. Careers at tech giants like Apple, Google, and Microsoft don’t all involve just coding end-user programs either. Each of these firms has their own client-facing staff that works with customers and partners to implement solutions. Field engineers at these firms may work as part of a sales team to show how a given company’s software and services can be used. These engineers often put together prototypes that are then turned over to a client’s in-house staff for further development. An Apple field engineer might show how a firm can leverage podcasting in its organization, while a Google field engineer can help a firm incorporate search, banner, and video ads into its online efforts. Careers that involve consulting and field engineering are often particularly attractive for those who enjoy working with an ever-changing list of clients and problems across various industries and in many different geographies. All jobs require employees to be professional and have a strong set of people skills in order to analyze problems; then develop, implement, and explain solutions.

Upper-level career opportunities are also increasingly diverse. Consultants can become partners who work with the most senior executives of client firms, helping identify opportunities for those organizations to become more effective. Within a firm, technology specialists can rise to be chief information officer or chief technology officer—positions focused on overseeing a firm’s information systems development and deployment. And many firms are developing so-called C-level specialties in emerging areas with a technology focus, such as chief information security officer (CISO), and chief privacy officer (CPO). Senior technology positions may also be a ticket to the chief executive’s suite.

Your Future

With tech at the center of so much change, realize that you may very well be preparing for careers that don’t yet exist. But by studying the intersection of business and technology today, you develop a base to build upon and critical thinking skills that will help evaluate new, emerging technologies. Think you can afford to wait on tech study, then quickly get up to speed? Think about it. Those who put off an understanding of technology risk being left in the dust.

While a focus solely on technology is a recipe for disaster, a business perspective that lacks an appreciation for tech’s role is also likely to be doomed. At this point in history, technology and business are inexorably linked, and those not trained to evaluate and make decisions in this ever-shifting space risk irrelevance, marginalization, and failure.

Key Takeaways

- As technology becomes cheaper and more powerful, it pervades more industries and is becoming increasingly baked into what were once nontech functional areas.

- Technology is impacting every major business discipline, including finance, accounting, marketing, operations, human resources, and the law.

- Tech jobs rank among the best and highest-growth positions, and tech firms rank among the best and highest-paying firms to work for.

- Information systems (IS) jobs are profoundly diverse, ranging from those that require heavy programming skills to those that are focused on design, process, project management, privacy, and strategy.

12009 figures are from http://www.indeed.com > Check to see how the figures have changed since 2009!

2CNNMoney, “Best Jobs in America,” 2009, http://money.cnn.com/magazines/moneymag/bestjobs/2009/snapshots/1.html.

3Fortune, “Best Companies to Work For,” 2007–2010. For 2010 list, see http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/bestcompanies/2010/full_list/index.html.

Pull up the 2018/19 list to see how the list has changed in the past decade!

Additional References

Gerdes, L., “The Best Places to Launch a Career,” BusinessWeek, September 15, 2008. Technology careers have actually ranked among the safest careers to have during the most recent downturn.

Hess, A. “The 10 best places to work in 2019, according to Glassdoor”, CNBC, December 10, 2019.

Kaneshige, T., “Surprise! Tech Is a Safe Career Choice Today,” InfoWorld, February 4, 2009.

Pontin, J., “But Who’s Counting?” Technology Review, March/April 2009.

Schmid, J. and B. Poston, “Patent Backlog Clogs Recovery,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 15, 2009.